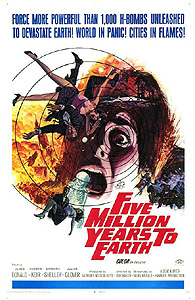

Five Million Years to Earth/Quatermass and the Pit (1967/1968) ***½

Five Million Years to Earth/Quatermass and the Pit (1967/1968) ***½

Remakes (broadly construed to include feature-film adaptations of television programs) and sequels to remakes were a major part of the Hammer business model throughout the studio’s mid-50’s-to-late-60’s glory years. Indeed, Hammer’s decline in the 70’s ironically coincided with an increasing reliance upon stories that no one had told on film before— and Hammer’s biggest money-makers in those days were its series of light comedies spun off from the hit TV show, “On the Buses.” (For that matter, the current Hammer resurgence also enjoyed its greatest success to date with a remake— 2010’s Let Me In— and the studio’s next project is reportedly an update of the highly regarded BBC telefilm, The Woman in Black.) By 1967, though, Hammer were clearly coming close to exhausting the supply of successful old properties on which to place their distinctive stamp. They’d just lowered themselves to remaking a Hal Roach movie, for Heaven’s sake, and their longstanding practice of strip-mining the Universal horror catalog had finally carried them to the bizarre expedient of importing William Castle to make them a version of The Old Dark House. There remained, however, one glaringly obvious remake target that Hammer had not yet touched. When the BBC aired “Quatermass and the Pit”— the most creatively ambitious of three serials recounting the exploits of Nigel Kneale’s scientist hero, Bernard Quatermass— in 1958, Hammer had already shifted the focus of their horror productions from science-fictional modernism to gothic revival. “Quatermass and the Pit” did not fit the new paradigm, and so there would be no third working holiday in London for Brian Donlevy in 1959. The 60’s brought a new emphasis on diversification, however, in terms of both tackling new genres (as when Hammer added swashbuckling adventure to its repertoire with The Pirates of Blood River) and pursing multiple approaches to individual genres simultaneously (as when the 1961 season treated fans of Hammer horror to Scream of Fear as well as The Curse of the Werewolf, and would have treated them to These Are the Damned, too, had marketing fears and censorship difficulties not gotten in the way). Now a third Quatermass movie made sense again, and Quatermass and the Pit (Five Million Years to Earth in American release) at last took its logical place alongside The Creeping Unknown and Enemy from Space.

The Hobbs End tube station is closed for reconstruction; one of the other underground lines is being extended in its direction, and the Hobbs End stop will become a transfer point between the two routes. The work is running a bit behind schedule as it is, so you can imagine how pleased the municipal authorities are when the excavation uncovers several apparently human skeletons. What looks at first like a matter for the police takes on a rather different coloration when the bones turn out to be fossils, and the cops yield their claim on the site to paleoanthropologist Matthew Roney (James Donald). This discovery is of enormous significance, too, for Roney dates the clay bed in which the bones were interred at some five million years’ age. That’s many times as old as the earliest known hominid species bearing anything like the combination of modern features seen in the Hobbs End specimens, so the skeletons in the tube station call into question everything we think we know about the early course of human evolution. But soon it’s Roney’s turn to have his work interrupted in favor of something more urgent, as his assistants dig their way to a huge, seemingly metallic object also buried in the ancient clay. Its size and curvature suggest an aerial bomb casing of some kind, and the bomb squad captain (Bryan Marshall, from Because of the Cats and The Witches) who responds to Roney’s summons tentatively identifies it as an unexploded German V-missile. That’s well beyond Captain Potter’s competence, so he places a call upstairs to request backup from an officer of sufficient age and experience to have dealt with Hitler’s most advanced weapons.

One such officer is Colonel Breen of the Royal Air Force (Julian Glover, from Theatre of Death and The Empire Strikes Back). He deals with rocketry from the other end these days, having just been appointed official military liaison to the hitherto strictly civilian Rocket Group overseen by Professor Bernard Quatermass (played this time by Andrew Keir, of Daleks: Invasion Earth, 2150 A.D. and Dracula, Prince of Darkness). Breen and Quatermass are in the office of some government weasel (Peter Copley, from The Man Without a Body and Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed), arguing over this restructuring of the latter’s program, when the telegram arrives directing Breen to Hobbs End. Quatermass comes along (he isn’t through fighting with the colonel yet), and thus is he on the scene to witness the rapid further escalation of the weirdness surrounding the tube dig. Weirdness like the buried machine looking very much unlike either operational model of V-missile once the workmen have enough of it exposed to get a fix on its shape. Weirdness like its fuselage being made of no material that Quatermass or Breen have ever heard of, apparently some sort of metal-based ceramic so heat-resistant that an oxyacetylene torch won’t so much as render it warm to the touch. Weirdness like the discovery of a sealed compartment toward the object’s nose, with no evident means of ingress from inside or out, the walls of which seem to respond almost consciously to attack by producing deafening sonic vibrations that no amount of damping will counteract. Weirdness like some of Breen’s men having hallucinations of big-headed, spectral dwarves much like Roney’s reconstruction of the ancient hominids galumphing around the excavation— hallucinations which strikingly recall centuries’ worth of ghost stories set in Hobbs End (or Hob’s End, to give the neighborhood its suggestively sinister original name). Roney’s assistant, Barbara Judd (Barbara Shelley, from Madhouse Mansion and Blood of the Vampire), finds the latter phenomenon especially interesting, and with Quatermass’s help, she pins down a recurring pattern to the old stories: the frequency with which they are reported cycles exactly in synch with activities that disturb the ground over the mysterious machine.

Inevitably, Colonel Breen and the defense minister (Edwin Richfield, of X: The Unknown and The Face of Fu Manchu) to whom he reports want nothing to do with any of this quasi-mystical mumbo-jumbo (although you’d think Quatermass’s opinion would carry just a little weight with officialdom now that he’s saved the world from extraterrestrial invasion twice). The thing in the tube station is an experimental V-weapon of unknown type, and Breen is goddamned well going to find a way to cut it open and defuse the warhead. But the weirdest thing yet happens when Breen’s expert on cutting un-cuttable things (Duncan Lamont, of Burke & Hare and The Creeping Flesh) has at the sealed compartment with his hardest, sharpest drill. The special tool makes no more apparent impression on the compartment’s aft bulkhead than anything else tried thus far, but for some inscrutable reason, the bulkhead shortly begins disintegrating of its own accord. What’s inside is unmistakably no warhead. In fact, it would take a man as willfully obtuse as Breen to interpret it as anything other than a cockpit— but the pilots, if that’s truly what they are, are not human! They’re not even Roney’s big-brained ape-men. Instead, they’re some manner of giant arthropod, like man-sized grasshoppers with half the usual number of legs arranged in a tripod pattern that bespeaks kinship with no Earthly anatomy. Roney and Judd (who have continued hanging around, despite Breen’s steadfast efforts to sideline them) scramble to keep ahead of the decomposition that sets in as soon as the outside air touches the carcasses, while Breen makes equally frantic haste to find some way of fitting a trio of monster crickets into his preferred explanation of the thing in the clay bed. Neither side is conspicuously successful. But the physical remains of what Quatermass is now satisfied to call the alien insects may not be the important thing in the end. Breen will deny this, too, even until it costs him his life, but there’s something else aboard that buried spacecraft— some sort of psychic residue of an extinct Martian civilization— and it’s more than a little apt that those whose minds were touched by it in ages past attributed its effects to demonic agency.

Far more than either The Creeping Unknown or Enemy from Space, Five Million Years to Earth bears the marks of narrative compression from a much longer running time. On television, the Quatermass stories each filled six 30-minute episodes. Having never seen any of the TV serials, I can’t say for certain what was cut from the original teleplays to fit them into roughly half that length, but a comparison between the three movies plainly indicates a substantial difference between this one and its predecessors with regard to irreducible complexity. That is, the fundamental premises behind “The Quatermass Experiment” and “Quatermass II” possessed a tightness and concision that facilitated reduction to feature length in ways that were not the case with “Quatermass and the Pit.” “Aliens mount stealth invasion of Earth by possessing and/or replacing humans” was a mainstay of cinematic sci-fi even before Nigel Kneale tried his hand at it, and “experimental rocket flight accidentally brings home space monster” became one soon afterward. Both are easily dealt with in 90 minutes or less. The mere fact that I can think of no way to boil “Quatermass and the Pit” down to a single sentence without doing serious violence either to some major aspect of the story or to English grammatical structure is a clear sign of its extraordinary ambition, and of its tailoring to a more expansive format. Simply put, this is the sort of tale that fans of literary science fiction constantly complain about never seeing in the movies, and Five Million Years to Earth demonstrates how much higher sci-fi on film could aim while simultaneously hinting at some of the reasons why it generally doesn’t.

Most people in the sci-fi business would be content to make a movie about the discovery that an alien civilization had guided the evolution of humanity, and what that might mean for us today. Or they’d be content to explore the political ramifications of ancient extraterrestrial technology turning up in an extremely public place at a time when the governments of even “free” societies had contracted an absolute mania for secrecy and knowledge-control. Or they’d be content to tell a ghost story in which the ghosts turn out to represent an eons-dead Martian culture. Or they’d be content to do the old invasion-from-within thing with the invasion occurring by psychic means across five thousand millennia. Five Million Years to Earth is all of those things, though, and a couple more besides— is it any wonder that it feels a bit overstuffed at only 97 minutes? Drastic shifts in focus necessarily come fast and furious, and now that I think about it, the turning points between the various subplots probably conform more or less to the episode breaks of the TV serial. Not all the elements are as well developed as I’d like them to be. Some of the technology that Quatermass and Roney use to discover what’s really going on is implausibly advanced for the apparently contemporary setting. The Martians’ aims in monkeying around with our earliest hominid ancestors never quite come into focus, and no rational objective seems congruent with what happens when the alien ship is fully dug up and the latent Martian “programming” of the human mind begins activating in response to the psychic signals emanating from Hobbs End. The means by which the invasion, for lack of a better term, is finally thwarted could stand a bit more setup, too, hinging as they do on both a bit of folklore that isn’t very well remembered today and a plot thread that had been seemingly left to trail off nearly an hour before. But while director Roy Ward Baker and screenwriter Nigel Kneale are visibly sweating to hold the story together on this unforgiving new schedule, they mostly succeed beyond the wildest dreams that either of the two prior Quatermass films might inspire.

I want to draw special attention to Kneale’s role as screenwriter on this outing, because I suspect that it’s pretty much the key to everything. The final shooting scripts for The Creeping Unknown and Enemy from Space had been Val Guest’s work, although Kneale had been more intimately involved with the latter movie than the former. This time, though, Kneale had it all to himself until shooting began, and the studio’s leadership had no good reason to interfere with him. The American sci-fi movies that effectively dictated the terms of Guest’s rewrites were fading into obsolescence. Hammer hadn’t needed American guest stars to sell their films to an overseas audience in many a year. Even the censor board had mostly given up the hard line they had consistently taken ten years before. Consequently, whatever got trimmed, compressed, or restructured along the way from the small screen to the big one on this occasion, it was Kneale’s call how to do it. Nowhere is that more evident than in the characterization of Professor Quatermass himself. Kneale had never been happy with the Val Guest-Brian Donlevy interpretation of his hero, and Five Million Years to Earth departs markedly from its predecessors on this point. Andrew Keir keeps the bluster and the arrogance (as anyone who remembers his turn as Father Sandor in Dracula, Prince of Darkness might predict), but the intimidatingly intelligent yet frighteningly reckless and ruthless antihero of The Creeping Unknown is nowhere to be seen. For all his prickliness and combativeness, this Bernard Quatermass is defined above all else by his wisdom. Enemy from Space had flirted with such a reading, but Donlevy wasn’t really up to selling it. Keir is. The mistrust of authority that had animated the second installment is also considerably heightened in the third. Colonel Breen and his masters in the Ministry of Defense don’t need to be infected with sentient alien microbes to behave with pigheaded disregard for the public welfare, and the resentment that Roney faces from the operators of the London Underground when he interrupts the work at Hobbs End for the sake of the most important paleontological find of the century is palpable. Ironically, the studio’s newfound willingness to stay out of Kneale’s way led to a movie that was, if anything, more in keeping with Hammer’s corporate character than the first two. There aren’t many starker dramatizations of cranky old fogies counter-typically bucking the system with all their might than Andrew Keir’s Quatermass verbally sparring with the Minister of Defense.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact