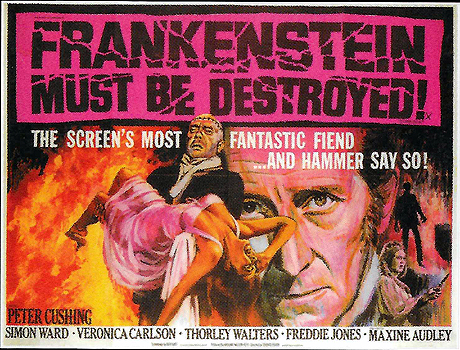

Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed (1969) ****

Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed (1969) ****

In 1969, Hammer Film Productions were still very much the team to beat in the international horror movie market. Indeed, it could be argued that the late 1960’s offered Hammer the most favorable environment that their product would ever enjoy. Relaxations in the British film-censorship regime meant that the studio could finally get away with things they’d been trying to do since about 1957, but the straitjacket hadn’t yet been loosened enough to permit the more aggressive but far less polished horror movies then being made in America and Continental Europe to make much impression on domestic audiences. Meanwhile, the game-changing advent of big-budget horror from the major Hollywood studios was still some years in the future, and the old fuddy-duddies in the company’s main office hadn’t yet fallen too far behind the swiftly evolving tastes of the youth market. Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed shows just how much Hammer could do with this combination of political freedom and economic strength. Many regard it as the best of all the Hammer Frankenstein films, and while I’m not completely sure I agree, I will say that only the revolutionary The Revenge of Frankenstein offers it any credible competition.

This installment in the long-running franchise also demonstrates that the currents of influence had begun to flow back into Britain as well as outward, for Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed’s opening scene would fit perfectly well into an Italian giallo. Dr. Otto Heidecke (Jim Collier) gets out of a carriage just down the street from the rowhouse where he lives and works, and begins walking the last couple blocks of his journey home. Unfortunately for Heidecke, someone is waiting for him on the front stoop with a sickle and a hatbox; the sickle goes into the doctor’s throat, and the doctor’s head goes into the hatbox. It’s easily the grisliest killing to be seen in any Hammer film up to this point, and both the murderer’s dress and the manner in which he is filmed is distinctly Bava-esque. A more specific point of resemblance to Continental antecedents comes to light when we see the killer’s face a few minutes later; scarred, pocked, burned, and sallow, it’s a dead ringer for the disfigured ex-Nazi in Antonio Margheriti’s The Virgin of Nuremberg. There’s also just a hint of The Awful Dr. Orlof in what happens next, for when the killer proceeds to his apparent base of operations in the long-disused Hertzberg mansion, he interrupts a petty criminal (Harold Goodwin, from The Phantom of the Opera and The Curse of the Mummy’s Tomb) in the process of breaking in to help himself to whatever saleable odds and ends it might still contain. The burglar retreats to the cellar, but that’s a very poor choice on his part— there’s a mad lab down there, and it, inevitably, is Decapitation Man’s ultimate destination. The thief narrowly escapes after being discovered, and runs off to tell his story to Police Inspector Frisch (Thorley Walters, of The Man Who Haunted Himself and Trog, in a role that was plainly conceived as comic relief, but commendably comes across as a forebear of Donald Pleasence in Raw Meat instead). Meanwhile, the killer hurriedly destroys as much of the evidence of his activities as he can in preparation for going on the lam, and as he does so, he pulls off the rather nonsensically overblown mask that he’s been using to disguise his identity. Turns out we know him rather well— he’s Baron Victor Frankenstein (Peter Cushing, for the fifth time).

Frankenstein, slippery as ever, is nowhere to be found by the time Frisch and his men reach the Hertzberg house to investigate, and all the cops have to show for their efforts is the pronouncement by Frisch’s medical examiner (Geoffrey Bayldon, from Asylum and The House that Dripped Blood) that the man they seek is almost certainly a doctor. The next we see of the baron, he’s checking into the Altenburg boarding house run by Anna Spengler (Veronica Carlson, of The Ghoul and Dracula Has Risen from the Grave) under the assumed name of Mr. Fenner. If you’re thinking this won’t end well for Miss Spengler, believe me, you haven’t guessed the half of it. Anna, you see, is in a very vulnerable position. Her elderly mother is confined to an expensive private sanatorium with some manner of nervous affliction, and Anna’s income from renting out her several spare rooms is just barely enough to pay for the old lady’s care, let alone cover Anna’s living expenses or taxes and maintenance on the house. Her boyfriend, Dr. Karl Holst (Simon Ward, later of Holocaust 2000 and Dominique Is Dead), is the pharmacist at the nearby Holberg Asylum, and he’s been abusing his position to help Anna make ends meet. For a year now, Karl has regularly smuggled cocaine certainly, and probably opiates as well, out of the asylum dispensary, selling them to addicts in his off hours and cooking the books at work to conceal the drugs’ disappearance. The scam has hitherto been very successful, but Karl and Anna never had to contend with Victor Frankenstein before. The baron has lived under Anna’s roof for only a few days before he discovers the landlady’s secret, and he immediately sets out to blackmail the couple.

It isn’t money that Frankenstein seeks. No, what he requires is an accomplice and a headquarters for a crime of his own. One of the patients in Holberg Asylum is an old correspondent of his, one Dr. Frederick Brandt (George Pravda, from the Dan Curtis TV Dracula). About five years ago, both doctors had gotten themselves into trouble by arguing not only that living brains could be transplanted (which Frankenstein, as we know, was already doing three movies ago), but that it should theoretically be possible to preserve an extracted brain indefinitely by freezing it. If successful, this line of research would offer the prospect of retaining for mankind the talents of geniuses who die of purely somatic ailments while their minds are still at the peak of their powers. (This, incidentally, is probably my favorite Frankenstein scheme ever. It sounds so perfectly beneficial and altruistic when Cushing lays it out, but the more you think about it, the more appalling it becomes. The political implications for any society seeking to carry out Frankenstein’s program, for example, are nothing less than nightmarish.) Frankenstein, for once in his career, met a scientific problem that he couldn’t solve, but Brandt managed to find a way to freeze a live brain without wrecking it. That was right before his own mind snapped under the strain of his work (or perhaps that of the fugitive lifestyle to which his work must have condemned him, if Frankenstein’s experiences are any indication), and he never did write his promised letter to the baron elucidating his discovery. Everyone from Holberg’s director (Peter Copley, of The Man Without a Body and Five Million Years to Earth) to Professor Richter (Freddie Jones, from Krull and The Satanic Rites of Dracula), the outside expert brought in recently to consult on Brandt’s case, considers the demented doctor to be incurable, but Frankenstein smugly tells Holst that “[his] medical education is about to be greatly expanded” when Karl raises the issue. Frankenstein’s plan is to have Holst sneak him into the asylum during the graveyard shift, show him to Brandt’s cell, and help him sneak Brandt out under light sedation. Then the baron will operate on Brandt’s brain to restore his sanity. He figures that Anna and Karl are in for about ten and twenty years in prison respectively should the authorities ever find out about their arrangements for paying Mrs. Spengler’s medical bills, so it really is to their advantage to cooperate, regardless of their opinion of the scheme.

Mind you, Frankenstein won’t be operating on anybody’s brain without a laboratory, and the thefts of surgical equipment necessary to construct one in the cellar (after Anna has evicted all her other tenants, obviously) tips off Inspector Frisch to the likelihood that his “mad and highly dangerous medical adventurer” has relocated to Altenburg. Bringing the medical examiner with him, Frisch sets off at once to pick up the trail. Matters are further complicated for Frankenstein and his unwilling accomplices when their final raid on a hospital-supply dealer’s warehouse unexpectedly ends with Karl stabbing the night watchman to death. Not only does the stabbing force Frisch to intensify his hunt, but it also raises the stakes for Karl and Anna substantially. Forget about a decade or two behind bars— now Karl can expect nothing less than the gallows, while Anna is looking at life in prison for harboring a known killer. Frisch is on the scene once again in the aftermath of the asylum-break, and interviewing Mrs. Brandt (Maxine Audley, from Peeping Tom and The Brain) brings to his attention the link between the vanished madman and the infamous Baron Frankenstein. In fact, Mrs. Brandt has actually seen the baron, although it was long enough ago that she can tell Frisch nothing about his appearance or whereabouts. However, we might plausibly expect her to recognize her husband’s old pal in the event that she were to encounter “Mr. Fenner” on the street one day. The biggest hassle for the malfeasant doctors, though, is the heart attack that Brandt suffers during his escape. Brandt won’t live but two or three more days, and there’s no chance of him surviving any brain operation. Frankenstein’s answer— to kidnap and murder Professor Richter, swap out his brain for Brandt’s, and perform the cerebral repairs after jumpstarting Richter’s body— has a certain evil elegance to it, but is actually not one of the baron’s better ideas. Leaving aside the question of how far Frankenstein can afford to push Karl and Anna, or of how many crime scenes Frisch can clean up without discovering something that will lead him to his quarry, how happy do you think Brandt is going to be to wake up strapped to a laboratory table in the body of a man he was up until recently too insane to remember ever meeting— especially since Brandt, unlike Frankenstein, still had the remains of a normal life awaiting him back home?

Hammer’s interpretation of Victor Frankenstein had always been at best an antihero. Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed, as the title implies, finally takes the last, decisive step toward turning him into an all-out villain. The shift in perspective has a lot to do with the change. Frankenstein himself was clearly the protagonist in all the preceding installments (although I suppose one could make a case for Hans Krempe instead in The Curse of Frankenstein), but Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed just as unmistakably makes the unfortunate Karl Holst the viewpoint character for most of the film. Impressively, director Terrence Fisher and writers Bert Batt and Anthony Nelson Keyes are so successful in making us see Frankenstein through Karl and Anna’s horrified eyes that we continue to do so even after the story leaves them behind to concentrate on the revived Brandt-Richter and his dogged campaign of vengeance. That last is an unexpected development in two ways, first simply because it is so drastic a shift in focus, and secondly because it takes up an aspect of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein that has been ill-served by the movies since at least 1931. The specific misdeeds at issue are different, of course, but this is the first instance I can recall of the cinema seriously employing Shelley’s theme of Frankenstein’s creature pursuing an avowed vendetta against his maker. It just goes to show how little use of the novel adaptations to other media have really made when so direct a lift can seem like a fresh departure as late as 1969— and as late as 2010, too, for that matter.

But to return to the subject of Frankenstein himself being the monster in Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed, it’s amazing how far a relatively minor expansion of the baron’s criminal resumé goes in that direction. Victor Frankenstein has been, from the very beginning, a manipulator, a back-stabber, a grave-robber, and a murderer, so it’s very odd that adding blackmail and rape to the charges against him should blacken his character as much as it does. I haven’t mentioned the rape of Anna Spengler until now because the scene is so purely gratuitous that it doesn’t fit very well into a summary of the plot. I dispute, however, the oft-raised objection that it is out of character for Frankenstein to do such a thing. Think back to The Curse of Frankenstein; in particular, think back to the way the baron treated both his fiancee, Elizabeth, and Justine, the maid with whom he’d been having an ongoing affair. If that was how he behaved toward women under his power back when he was still youngish and idealistic, then why should we expect the older, bitterer, and infinitely more cynical Frankenstein of this episode to scruple at anything? I also have to appreciate the rape scene for giving Peter Cushing a chance to demonstrate that he could, under the right circumstances, portray physical menace despite his spindly build, mild demeanor, and relatively advanced age. Cushing truly is scary when he corners Anna in her bedroom while Karl is out working the night shift, and the complete absence of recognizable pleasure in his expression during the attack itself is more chilling than any salacious leer could ever be, even if it was more a reflection of the actor’s very real distaste for the material than a conscious performing choice. Furthermore, while some might hold it against Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed that the subject is never raised again after the fade to black, I found that offhand attitude a potent reminder of the horror of Anna and Karl’s situation. So utterly at Frankenstein’s mercy are they that they can’t afford to raise a fuss over even that foul an abuse. It’s just one more thing making this probably the bleakest and most hard-hearted film Hammer had made since These Are the Damned.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact