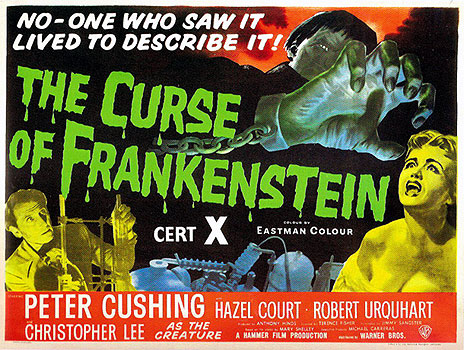

The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) ***½

The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) ***½

Way back around February of 2000, I wrote a review of The Curse of Frankenstein. Like most of the reviews from my first year as an amateur movie critic, it wasn’t very good— heavy on mere story recap, light on analysis, and positively quivering with the defensive brashness of youth. It also perplexed a lot of readers over the years, if my e-mail inbox is any indication, since my interpretation of The Curse of Frankenstein’s final scene turned out not to be half as obvious as I imagined. I must have written a hundred comparably crummy reviews, however, between August of 1999 and the following October, when the realization that I’d almost accidentally written a few really good ones as well convinced me that I could, and therefore should, do better. For the most part, I’ve been content to let those early reviews stand almost as written, giving them just a bit of polish on my periodic stem-to-stern maintenance sweeps of 1000 Misspent Hours and Counting, but I’ve finally decided that something more drastic is called for in the case of The Curse of Frankenstein. That’s because my original review of this movie, in addition to the aforementioned defects, embodied an embarrassingly Dunning-Krugery failure to appreciate the film’s place in history. I first came to The Curse of Frankenstein knowing only that it was among the most highly regarded of a whole swarm of cheap late-50’s mad-science flicks in a nostalgic medical horror vein. It didn’t occur to me that it might be the cause of that swarm, let alone that it was the first step in a tonal transformation of the horror genre that would reach completion with Night of the Living Dead eleven years later.

Well, I suppose I knew one more thing about it. I also knew that The Curse of Frankenstein was a significant film in the evolution of a British studio called Hammer Film Productions— but even that I knew in a way that led me astray at first. You see, The Curse of Frankenstein was only the third Hammer film that I consciously watched, although subsequent viewing would shoot off memory flares revealing that I’d seen several more as a kid without recognizing them for what they were. Furthermore, my limited previous exposure to the studio’s output was not conducive to reaching a coherent esthetic judgment, consisting as it did of the magisterial The Mummy on one hand, and the dull and witless The Gorgon on the other. In the absence of personal familiarity, I had only my reading to fall back on. And the writers of the books on horror and monster movies that I’d devoured throughout my childhood and early adolescence in the 1980’s almost uniformly denigrated Hammer as an uninteresting remake factory. To be sure, I was aware that a vocal Hammer fandom existed, but every form of worthless crap has a vocal fandom somewhere, you know? While The Curse of Frankenstein went a long way toward making a Hammer fan out of me personally, that alone seemed no obvious reason to put any great effort into writing about it. So now that I’ve taken up most of a page explaining why my old Curse of Frankenstein review sucked, let’s see if I can build something that doesn’t suck out of its carcass.

The movie begins with Baron Victor Frankenstein (Peter Cushing, beginning an association with Hammer that would permanently reshape his previously undistinguished career) in his prison cell, receiving a visit from a priest (Alex Gallier). Frankenstein has an incredible story to tell, and his last hope for exoneration lies in the remote possibility that it will be believed by someone as influential as a man of God. The baron figures that with the clergyman’s help, he might be able to convince the authorities that he is not responsible for whatever misdeed has landed him in the waiting line for the guillotine. The priest himself doesn’t think that his opinion would be of any use to Frankenstein at this juncture, but he agrees to hear the prisoner out anyway.

The baron begins the tale in his fifteenth year (when he was young enough to be played not by Cushing, but by Melvyn Hayes, of The Flesh and the Fiends). That was the year his mother died, leaving him sole heir to the Frankenstein fortune. It was also the year that he met Paul Krempe (Robert Urquhart), the man who was to become first his teacher, and then his partner in the scientific pursuit of the secrets of nature. Frankenstein and Krempe were nothing if not ambitious; the main object of their investigations was the mechanism of life itself. Fortunately, or perhaps unfortunately, they possessed talent equal to their ambition, and by the time Frankenstein was a young man, he was able to perform such astonishing feats as restoring life to dead animals.

Krempe was content with the work as it stood, as pretty much any biologist of the day would be— bringing dead puppies back to life is some pretty hot shit, you know— but Frankenstein believed that he had only reached the first stage. He would not be satisfied until he had created life where none had existed before. One could argue that his plan— to build a man from spare parts, and then to animate him by electrochemical means— would constitute cheating, seeing as all of the parts would have been previously alive, even if they had hitherto been segregated in the bodies of several different individuals, but even so, it would still be a mighty impressive achievement if it worked. After some prolonged wrangling, Frankenstein was able to convince Krempe to assist him, starting with the theft of a criminal’s body from the gallows. All Frankenstein wanted from the dead thug was a chassis, if you will. Such important parts as hands and a brain were to come from other, more socially acceptable corpses. It was probably when Frankenstein started sawing off the body’s head that Krempe changed his mind about the value of the work. In that moment, he saw for the first time how his and Frankenstein’s experiments would look to someone not involved in them, and he decided that that hypothetical someone’s impressions were probably right. Try telling that to Frankenstein, though— talk about a tough room! Nothing Krempe could say would convince his companion, and the two men settled into a routine in which the baron would spend most of his time up in the lab, while his former tutor just sort of hung around the house, worrying about what would happen if Frankenstein’s work were a success.

A complication arose at that point, in the form of Frankenstein’s first cousin, Elizabeth (Hazel Court, of Devil Girl from Mars and The Premature Burial), to whom he was arranged to be married. Neither Krempe nor Justine (Horror of Dracula’s Valerie Gaunt), Frankenstein’s maid and mistress, knew anything about that on the day when Elizabeth’s mother died, and the girl herself arrived on the baron’s doorstep in need of a place to live. Naturally Justine was not happy to have competition, especially since Frankenstein had been stringing her along for years with the promise that they would be married just as soon as he was satisfied with the results of his experiments. Nor did the baron himself do as much as might be desired to make Elizabeth feel welcome in her new home. Even Krempe almost immediately turned his efforts to persuading Elizabeth to move out, although his motivation was rather different. Krempe very quickly developed a considerably stronger affection for Elizabeth than her fiancé had, and it horrified him to contemplate that innocent girl living underneath a workshop for high-tech necromancy.

But to return to Frankenstein and his project, the baron had very high standards for the more sensitive components of his creature. The hands had to come from a sculptor, the eyes from a painter, and so on. And for the brain, the most vital piece of all, only a genius would do. Of course, artists exist in sufficient quantity, and lead sufficiently precarious lives, that their limbs and organs became available frequently enough. The rarity of geniuses, however, is such that Victor couldn’t simply wait around for one to finish using his brain; a more pro-active approach was called for. This was the point at which Frankenstein left his last scruple behind him, inviting a respected old scientist (Paul Hardtmuth, from The Atomic Man and The Gamma People) over for dinner, and arranging for him to meet with a little “accident.” He chose his victim well, too, for the old man had no living relatives. There was no one to object to Frankenstein having him interred in his own family crypt, where his coveted brain would be readily accessible. Unfortunately for Frankenstein, Krempe made one last play to prevent the completion of the baron’s creature, with the result that the brain was seriously damaged before it could be installed. Victor made what repairs he could before proceeding, but when the creature (Christopher Lee, in one of the last roles for which he was cast more on the basis of his 6’5” height and colossal physique than for his equally impressive acting ability) was activated, it became apparent that just about the only thing Professor Bernstein’s brain had retained was the memory of who had killed him. Frankenstein’s synthetic man proved exceedingly troublesome, not just to him, but to the entire community. Indeed, it was the creature that committed the crimes for which Frankenstein now stands condemned. The trouble is, it became necessary to destroy the thing utterly, and now the baron can’t present a shred of proof that it ever existed in the first place…

As with nearly all Frankenstein pictures, you’d be hard pressed to find Mary Shelley’s novel hiding between the lines of this movie’s script. You’d be equally hard pressed, though, to find any trace of the stage play that originated with Peggy Webling, and then passed through the hands of John Balderston and Louis Cline on its way to being picked up for film adaptation by Universal— or, indeed, of the Frankenstein script, obviously inspired by the Universal picture, which Hammer had bought from Milton Subotsky and Max J. Rosenberg (who would go on to found Amicus Productions, the closest thing to a serious rival that Hammer ever had in the market for British horror films) in 1956. That’s because television had given the old Universal horror movies a new lease on profitability, leading the studio to become exceedingly zealous in defending their intellectual property rights regarding them (and indeed in asserting a few new ones of dubious legality). If Hammer wanted to make a Frankenstein of their own, they would have to go far out of their way to ensure that it bore no detectible resemblance to the American studio’s. There could be no lightning-catching apparatus at the top of a medieval watchtower, no sadistic hunchback, no mistaken theft of a criminal’s brain, no torches-and-pitchforks mob. Most of all, Hammer makeup artist Philip Leakey had to come up with a look for the monster that didn’t in any way recall Jack Pierce’s character design, which eight movies over seventeen years had permanently cemented as the appearance of Frankenstein’s creation in the minds of anyone who might imaginably buy a ticket to The Curse of Frankenstein. Enjoined from doing exactly the things that one would instinctively try when making a Johnny-come-lately Frankenstein flick, Hammer had to get aggressively creative.

The approach taken by the studio could perhaps have been anticipated by someone who paid close attention to the marketing of Hammer’s previous, sci-fi-inflected horror films, particularly The Quatermass Xperiment and X: The Unknown. Those Xes were as in “X Certificate,” the adults-only rating recently introduced by the British Board of Film Censors, which all but the very mildest horror movies (and even a few of those) were virtually guaranteed to be assigned throughout the 50’s and 60’s. Hammer bosses William Hinds and Michael Carreras reckoned that if they were getting stuck with X Certificates no matter what, they might as well try to ballyhoo them into a virtue. The gambit worked, too, since a series of shrewd partnerships with American distributors gave Hammer access to far bigger audiences than the ones they’d lose from domestic theaters turning away punters under sixteen. I like to think of the mature version of the strategy, which The Curse of Frankenstein inaugurated, as “Tits, Gore, and Eastmancolor.”

To be sure, there was as yet no nudity allowed on English-speaking movie screens— at least not in the kinds of mainstream venues where The Curse of Frankenstein was intended to play. Nevertheless, the erotic content of this movie and its successors was extraordinarily strong for its day, with the lowest necklines, the deepest cleavage, and the most thinly veiled sexual perversity. Cinematographer Jack Asher had one hell of a knack for photographing beautiful women, too, and all that blushing flesh is positively radiant on the Eastmancolor film stock (at least until it starts fading to sepia, as that cheap and chemically unstable film was prone to do). In The Curse of Frankenstein specifically, eroticism in all its forms is manifested most starkly in Valerie Gaunt’s Justine. The camera is rightly besotted with her, and Asher is constantly pointing it straight down the front of her dress. Beyond that, the nature of Justine’s relationship with Frankenstein is itself an affront against cinematic propriety, and the punishment she ultimately receives (thrown off-camera to the monster after attempting to blackmail Frankenstein into marrying her instead of Elizabeth) is implicitly an even bigger one. We may not know what the creature does to her behind that locked laboratory door, but just the same, we kind of do.

It wasn’t the eroticism, however, that earned The Curse of Frankenstein its X Certificate, or that led contemporary critics to decry it as “disgusting,” “degrading,” or “a peep-show of freaks interspersed with visits to the torture chamber.” No, what really incensed the self-appointed guardians of public morality and good taste was the unprecedented explicitness of this movie’s physical horrors. As is usually the case with these things, subsequent developments have tended to soften the impact for modern viewers, making it hard to understand what all the fuss was about. After all, Blood Feast, the movie that conventionally gets credited as the original gore film, would come out only six years later. But without The Curse of Frankenstein and the uproar over it, it’s doubtful that Herschell Gordon Lewis and David Friedman would even have thought to include “gore” as an item on their brainstorming list of things to consider trying next as the market for nudie-cuties started to soften in 1963. Victor Frankenstein spends much of the movie bringing home parcels from out of town, containing severed hands, extracted eyeballs, and assorted similar delicacies— and for the first time in a British horror movie, these items are clearly shown to the audience in all their plausibly blood-smeared glory. The baron’s lab is a smorgasbord of bottled limbs and organs, none of which exhibit the pristine cleanliness of the brains in jars that we’ve been accustomed to seeing in mad science movies from James Whale’s Frankenstein to Donovan’s Brain. No, these things all look dead, and what’s more, a little bit rotten, as if Frankenstein’s preservation technique could still do with a bit of refining. But The Curse of Frankenstein’s crown jewel of repugnance is, appropriately, Philip Leakey’s rendition of the monster itself. I’m not a fan of Christopher Lee’s performance in the part, which has none of Boris Karloff’s sensitivity, and achieves more bathos than pathos. But there has never been a more visually impressive interpretation of Frankenstein’s creature in all the annals of cinema, and the only one more viscerally revolting (Paul Blaisdel’s version from I Was a Teenage Frankenstein) is just a tacky copy of Leakey’s, turned up to eleven. Like the lab specimens, the monster is a perfectly believable product of cobbling together dead things well past their sell-by dates, and the mask of oozing sutures that is its face implies a much more involved and invasive assembly process than I’m used to thinking about in Frankenstein adaptations. And again as with the eroticism, Asher’s vibrant color cinematography gives all this movie’s hideousness a vital immediacy that no previous version had ever attained.

But The Curse of Frankenstein’s most shocking innovation is that of screenwriter Jimmy Sangster, abetted by a riveting performance from Peter Cushing. Acting on instructions from Will Hinds to “make Frankenstein a shit,” Sangster wrote the baron as a monster at least co-equal to the thing in his laboratory, but crucially retained him as the film’s viewpoint character. In contrast, Paul Krempe, the voice of decency, is a weak and ineffectual presence throughout, unwilling to break with Frankenstein completely for fear of what might happen if he should succeed unsupervised in his experiments, but unable to restrain his former pupil from anything he sets out to do. The result is a genuinely unsettling moral ambiguity in which you can’t help rooting for a guy whom the movie forthrightly presents as utterly and irredeemably evil. And even once the creature is destroyed and Frankenstein gets his comeuppance, normality cannot be said to have been restored, which leads me back to that less-obvious-than-I-realized interpretation of the ending I mentioned.

There are two things happening here, both of which have black implications for the character of Krempe, whom we’ve been encouraged to think of as the good guy despite all his Hamlet-like indecision and general uselessness. After the priest leaves Frankenstein to his fate, Paul comes round for one last visit before his old friend’s date with the guillotine. Victor starts begging him to intervene on his behalf, too— but hang on a minute. If Frankenstein has been sentenced to die, then surely he’s already had his trial. And surely Paul Krempe, Frankenstein’s oldest friend and roommate of heaven knows how many years, would have been the first witness the court called, after perhaps the defendant himself. Furthermore, Frankenstein is to be executed not as the monster’s creator, but as the personal perpetrator of the monster’s crimes; the authorities didn’t even believe him that there ever was a monster. You see what this must mean, don’t you? Paul sold Victor out at his trial! And now here he is outside Frankenstein’s cell to gloat about that. And as if that weren’t enough, he brings Elizabeth with him— Elizabeth, who was seriously wounded during the climax, but who now seems just the slightest bit inconvenienced by injuries that should have left her incapacitated for weeks given the state of the medical arts in the 19th century. I’m less sure about this than I used to be, considering how often genre films take a “hit point” approach to non-lethal wounds, but I can’t help noticing that Elizabeth’s new boyfriend is the one person other than Victor himself who would know how to use Frankenstein’s proprietary surgical techniques. So maybe Krempe isn’t just gloating here. Maybe he’s also showing off his handiwork to the one person alive (for the moment) who would recognize and appreciate it.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact