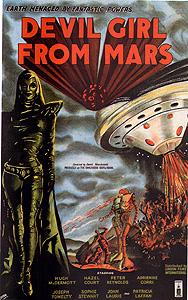

Devil Girl from Mars (1954) -**˝

Devil Girl from Mars (1954) -**˝

Devil Girl from Mars is a rare bird indeed— a British sci-fi film that predates the epoch-marking release of The Creeping Unknown/The Quatermass Xperiment. But whereas The Creeping Unknown and its sequels were well written, solidly directed, and seriously handled explorations of the territory where sci-fi and horror meet, fully qualified to stand in the company of The Thing and Invasion of the Body Snatchers, Devil Girl from Mars owes more to the likes of Cat Women of the Moon. Despite the illusion of class conferred upon it by all those distinguished-sounding English accents, this is a very silly film at bottom, and is much better represented by its awesomely lame robot suit than it is by the frosty dignity of nominal star Hazel Court.

Given that this is a British movie, you’d almost feel cheated if it didn’t spend at least a little of its time at a remote manor on the Scottish moors, and indeed that is the very first place that Devil Girl from Mars takes us. That manor has been converted into an inn by its owners, the Jamiesons (John Laurie, from The Reptile and The Abominable Dr. Phibes, and Sophie Stewart, of Things to Come and Murder in the Old Red Barn), and when we first meet them, Mrs. Jamieson and Doris the maid (Adrienne Corri, from The Tell-Tale Heart and Vampire Circus) are taking a breather from their duties to listen to the news on the radio. The big story this night concerns an airliner that exploded in midair for reasons unknown, showering the Scottish countryside with flaming debris. (Shades of Pan-Am flight 103!) Meanwhile, astronomer Professor Arnold Hennessy (Joseph Tomelty, also in Timeslip and The Black Torment) is hopelessly lost on the moors in the company of a reporter by the name of Michael Carter (First Men in the Moon’s Hugh McDermott). Hennessy and Carter are looking for a huge meteorite that ought to have landed in the vicinity, but so far, all they’ve managed to find is a whole lot of fog. Eventually, the men give up and put in at the Jamieson place, which would otherwise be entirely destitute of tenants beyond actress Ellen Prestwick (Court, from The Raven and Dr. Blood’s Coffin).

They’re not the only ones dropping in, either. Also on the prowl this night is a fugitive from the law, one Robert Justin (Peter Reynolds, from the 1961 version of The Hands of Orlac), who was sent up for killing his wife— accidentally, or so he maintains— some time ago. Justin is seeking out the inn because Doris is his ex-girlfriend, and he hopes to receive some sort of aid or at least sympathy from her. Robert apparently knows his ex well, for manslaughter conviction or no, she agrees to help him fake an identity. Presenting him to her boss as a wayfarer named Albert Simpson, who lost his wallet after falling into a nearby stream, Doris talks Mrs. Jamieson into letting Justin stay on at the inn for a few days in exchange for his services as a handyman. The ruse might have gone undiscovered, too, were it not for Michael Carter. Carter happened to do some reporting on Justin’s case, and he recognizes the fugitive when the two men cross paths later that evening. But luck is with Justin in at least some small way, for though he loses his shot at being Ellen’s love interest, he and everybody else at the inn are soon to see that they have much more important things to bother about than his prison break.

Bet you were wondering when the promised Devil Girl was going to show up, huh? Well wonder no longer, for a statuesque woman (Patricia Laffan) in an outfit halfway between Darth Vader and dominatrix strides purposefully into the inn’s lobby just as Robert Justin’s secret is coming out. Nyah is her name, and she has come from Mars on a mission of utmost importance to her people’s survival. You see, on Mars, the phrase “battle of the sexes” is to be taken literally. Centuries ago, tensions between male and female Martians erupted into open warfare; the women triumphed in the end, but at the cost of exterminating all but the weakest and most servile of their menfolk. Needless to say, this has not been good for Martian society in the long run, and matters have now gotten so far out of hand that the women of Mars have decided to import worthier breeding stock from neighboring Earth. The plan had originally been for Nyah to land in downtown London, where the pickings would have been rather better, but her ship was damaged upon reentry— evidently Earth’s atmosphere is substantially thicker than the engineers who designed the spacecraft had anticipated. (Insert your own joke about women’s aptitude for conventionally masculine occupations here... Try it, it’s fun!) We may reasonably infer both that the crippled spacecraft is the true identity of that meteor Hennessy was chasing, and that Nyah is somehow responsible for that airplane that blew up a while back. While her ship repairs itself (the self-replicating organic metal of which Nyah’s vessel is constructed is one of this movie’s cooler ideas), the Devil Girl figures she may as well see which of the local males might be worth the trouble of hauling home to Mars.

It’s a pity Nyah’s people couldn’t wait another forty years to launch her expedition, and an even bigger one that they picked the British Isles as the site of her landing. I personally know several virile young men who would be happy to accept professional positions knocking up Martian women, especially if Nyah herself is truly representative of her kind. But the men at the inn are a conservative lot, deeply offended at the notion of a world where a handful of limp-dicked girly-men are ruled over by stern, leather-garbed ladies of discipline, and much indignant harrumphing greets Nyah’s explanation of her intentions. She responds with a little show of force. First, Nyah invites Professor Hennessy out to her ship to stare in slack-jawed amazement at the technological marvels of Martian civilization. Then she incinerates the Jamiesons’ Expendable Meat hunchback handyman with her raygun. Finally, she adopts the two-pronged strategy of kidnapping the Jamiesons’ little grandson, Tommy, and turning her pet robot loose to vaporize much of the landscaping on the manor’s grounds. Realizing at this point that the only road to victory runs through guile and treachery, Hennessy suggests that one of the men at the inn agree to go to Mars with Nyah in exchange for the safe return of Tommy. This selfless volunteer, after a bit of coaching from Hennessy, will sabotage the Devil Girl’s spacecraft after liftoff. Hennessy at first offers to do the dirty work himself, but Carter convinces him that he is much too old and feeble to appeal to Nyah, and therefore has no chance of being accepted aboard her ship. Carter means to go instead, but at the last minute, Justin outmaneuvers him for role of self-sacrificing redeemer, atoning thereby for the inadvertent slaying of his wife. Naturally, no one ever thinks to comment on the irony of making up for killing one woman by blowing another to atoms in the Earth’s ionosphere.

I fear this is going to sound almost monomaniacal, given how little screen time the stupid thing actually gets, but the thing that really sticks with me about Devil Girl from Mars— and which I suspect will stick with just about anybody else who sees it, too— is that goddamned robot. It’s obviously intended to evoke anxious memories of Gort’s first appearance in The Day the Earth Stood Still, for the two machines make their entrances in exactly the same manner. But oh, what a difference! Despite the limitations of the suit itself, Gort has an undeniable screen presence which forces the viewer to take him seriously. This robot, on the other hand... Tom Servo is both scarier and more convincing. Standing almost nine feet tall through the magic of forced perspective, the robot’s body consists of a large, rectangular box with a handful of apparently purposeless widgets arrayed across its chest. Legs lacking even a single point of articulation project downward out of the skirt formed by the open lower end of said box, while the arms are pincer-tipped tentacles seemingly composed of telescopically stacked styrofoam coffee cups. And the head— oh my God, the head! It’s nothing but a big glass dome atop the shoulders, inside which we can discern some sort of humongous lightbulb. It’s a sight to behold, let me tell you. And Nyah takes such pride in her uniquely unimpressive mechanical companion, too. It reaches that rarefied level of wrong at which you might plausibly defend the film against criticisms of its entertainment value by saying, “Yeah, sure— but did you see that fucking robot?!?!”

Speaking of criticizing Devil Girl from Mars’s entertainment value, the most likely angle of attack for that is the movie’s pacing. There is way too much talk in this flick, and what little action it contains is far too enclosed for the movie’s good. There’s the inn itself, the inside of Nyah’s ship, and the short stretch of moor between the two locations; if something doesn’t happen in one of those places, then we only get to hear about it. This unfortunate point plays up what might be the most astonishing fact about Devil Girl from Mars, that it was adapted from, of all things, a stage play. Who knew they were doing sci-fi on stage in Great Britain in the early 50’s?! In any event, stage plays are notoriously difficult to translate to the screen, and the makers of Devil Girl from Mars didn’t do themselves any favors by trying. Even with a Martian S&M queen running around zapping people with rayguns and siccing the galaxy’s shittiest robot on sheds and trees and shrubberies, there are long stretches of this movie that are soul-suckingly dull. All I can say to you by way of explanation for why I mostly enjoyed the film anyway is, “Yeah, sure— but did you see that fucking robot?!?!”

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact