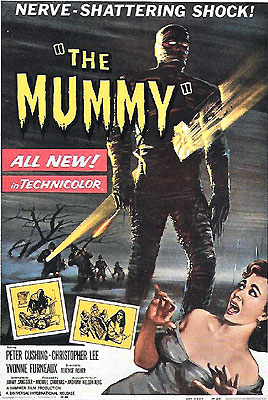

The Mummy (1959) *****

The Mummy (1959) *****

Hammer Film Productions’ 1959 The Mummy (not so much a remake of the 1932 film as a composite of all five Universal mummy movies) is everything all those über-famous Universal Studios flicks from the 30’s and 40’s should have been, but mostly weren’t. This is perhaps an unfair comparison, as Hammer had an extra 15-30 years to overcome the staginess that plagued so many very old movies, but considering how far The Mummy towers over even its contemporaries, I really think there must be something more at work than time alone. If I had to guess, I’d say that something is a combination of pacing, an unusually astute script, and top-notch performances from Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee, who in this film acts the pants off just about everybody in Hollywood today, using his eyes alone.

After more than 40 years, the story of this film probably offers no surprises, but here goes. The year is 1895, and the famous archaeologist Stephen Banning (Felix Aylmer) is in Egypt with his brother Joseph (Raymond Huntley, from The Ghost Train and So Evil My Love) and his son John (a startlingly young Cushing), excavating what he hopes is the long-lost tomb of the 20th-dynasty princess Anankha. John is currently unable to take full part in the dig, because he broke his leg some five days earlier, but he is determined to stay in the field-- he has no intention of missing the excitement in the event that his father really has found Anankha’s tomb. Just after the Bannings’ laborers finally break through the layers of rubble blocking the entrance, a well-dressed Egyptian man (George Pastell, Hammer’s favorite ethnic actor-- we’ll later learn that the character’s name is Mehmed Akhim) arrives to warn the Bannings of a curse laid upon the tomb in ancient times. Stephen thinks this curse to be nothing but ridiculous superstition, and enters the tomb anyway, his brother at his side.

The tomb proves to be all that he had hoped. Not only is it really the tomb of Anankha, it has miraculously been spared the depredations of the 4000 years’ worth of grave robbers who ravaged so many of the ancient tombs. Anankha’s mummy is there, along with her vast fortune in grave-goods, including a hitherto-considered-legendary text called the Scroll of Life, the latter preserved in a cartouche-shaped box inlaid with lapis lazuli. Stephen sends Joseph to tell John of the discovery, and the younger Banning brother hurries away. Moments after Joseph has left the tomb, however, he hears his brother screaming within. When he reaches Stephen’s side, the latter man has collapsed across the princess’s sarcophagus, and looks to be in deep shock, muttering incoherently to himself and seemingly oblivious to his surroundings.

Three years later, John has come to see his father at the nursing home to which he has been confined since that day in Egypt. For the first time in all those years, the elder Banning has emerged from his catatonia, and asked to see his son. The reason for Stephen’s concern stems from what he saw back in the tomb. The way he tells it, he did not have a stroke (the doctors’ best guess as to his affliction). Rather, as he read aloud the text of the Scroll of Life, the ancient incantations brought to life a mummy (Anankha’s? Someone else’s?), which attacked him, bringing on his present debility. Stephen is unshakably convinced that this living mummy is now coming to England to kill him, along with Joseph and John, who were accomplices in his violation of the tomb. John takes the old man’s ramblings as well as could be asked (though, watching him, one gets a clear sense of “I came all the way out here for this?!”), and tries to persuade him that he is mistaken, and is simply suffering from an attack of nerves. Disgusted at his son’s disbelief, Stephen sends him away.

Not much time has passed, however, before we begin seeing evidence that Stephen knew what he was talking about. A pair of cartmen are sitting in a tavern, discussing over drinks their current assignment. Apparently a “foreigner” has commissioned them to transport a crateful of ancient Egyptian relics to his newly-acquired home in the countryside about half a mile away from the tavern. The trip to the house takes them past Stephen’s nursing home, which doubles as an insane asylum, just as the asylum’s alarm begins to sound. Afraid that the alarm heralds the escape of some dangerous lunatic, the cartmen whip their horses to a higher speed, despite the worsening condition of the road ahead. Predictably, the cart hits a massive bump in the road, causing their employer’s crate to fall overboard into a deep bog. The cartmen don’t much care; at this point, they just want to get away from the asylum.

The next day, the police are questioning one of the cartmen as they attempt to dredge up the crate. Just then, the “foreigner” who hired them shows up to see what all the fuss is about. You probably don’t need me to tell you that this man is none other than Mehmed Akhim. Mehmed is suspiciously unconcerned about the fate of his relics. I don’t know about you, but if I’d just lost thousands of pounds’ worth of irreplaceable Egyptian artifacts because of the clumsiness of the movers, I’d be pretty fucking pissed. But not Mehmed; he just nods his head and goes back home when the police inform him that his crate is in all probability irrecoverable.

He comes back that night, though, with a familiar-looking papyrus in his hands, and begins to read it over the bog. The incantation is full of worrisome phrases like, “Make supple these limbs, and strong these sinews, and give them not to corruption,” and it is rather less than surprising that the recitation results in Christopher Lee, wrapped in bandages and clotted with mud, rising from the bog. Mehmed Akhim instructs the mummy to seek out and destroy those who have desecrated Princess Anankha’s grave, and the next thing we know, the moldy old hulk is smashing his way into Stephen Banning’s hospital cell to strangle him.

Now, it should be fairly obvious that Christopher Lee is not Princess Ananakha, so some explanation is clearly in order. Back in 20th dynasty days, Anankha made a pilgrimage to the Temple of Karnack to perform some important religious observance or other. She never reached the temple alive. Her actual fate remains unknown, but her body was recovered by Kharis, priest of the Temple of Karnack (Lee), and was buried with all the grandeur due a princess and a priestess-- with one exception. Instead of following the customary practice of sending the body back to the royal capital for interment, Kharis had Anankha buried locally, in a location known only to him and to the builders of the tomb-- all of whom he immediately had killed. The reason for Kharis’s departure from orthodoxy was that the priest was in love with the princess, but was kept from her by her religious vows. The trick is that Anankha’s vows were only binding during her lifetime. With her death, she was released from them, and was free to do what she wished. The ever-resourceful Kharis was not troubled by the obstacle that the princess’s death would seem to present to a fulfilling relationship, because he possessed the Scroll of Life, whose incantations held the power to raise the dead. So he naturally wanted to keep the body of his love close by. Unfortunately for Kharis, he was discovered before he could complete the spell, and sentenced to be buried alive in Anankha’s tomb. Before he died, a spell was placed over him pressing him into service to stand guard over Anankha forever.

The collision course with Kharis on which that spell places the Bannings should be obvious, and the main outlines of the film’s principal conflict should be equally so. The complication that will get us to the all-important scene in which the mummy staggers off into the night carrying a beautiful, unconscious girl is similarly predictable. John Banning’s wife, Isabel (Yvonne Furneaux) bears a striking resemblance to Anankha. I’m sure you see where this is going.

The thing is, though, that The Mummy suffers not a bit from all this predictability. Sure, all but the most dim-witted viewers will be two or three steps ahead of the film the entire time, but in this case, that somehow adds to the film’s effectiveness. Watching The Mummy is like watching a complex but graceful and elegant machine at work. You already know what the end result will be, but the pleasure is in seeing the process itself. The Mummy’s predictability is the predictability of rightness rather than of intellectual laziness, and the only misstep in the entire film is the conspicuous lack of an explanation for Isabel’s unconsciousness when the mummy absconds with her-- one moment, we see her menaced by the mummy, the next, we see it carry her through the door. Sure, several obvious explanations present themselves, but something in the structure of the scene makes it seem like we were supposed to see her faint or be knocked out or whatever. But it’s a minor flaw, and is vastly outweighed by the film’s many strengths. Especially satisfying is the way screenwriter Jimmy Sangster weaves together all the best elements from The Mummy, The Mummy’s Hand, The Mummy’s Tomb, The Mummy’s Ghost, and The Mummy’s Curse into a narrative far more coherent and compelling than those upon which it was based. Though much longer than any of the Universal films, and more deliberately paced than any but the original The Mummy, this version holds the viewer’s attention in a way that none of its models do-- not even the ones that are only an hour long! Finally, even if this version of The Mummy had nothing else to recommend it, it could still succeed on the strength of the awesome screen presence of Christopher Lee. Even with scarcely any dialogue (and none at all as the mummy), Lee dominates the film, even upstaging Peter Cushing for once. His Kharis is the only living mummy ever filmed that doesn’t make you say, “why the fuck doesn’t anybody just go around him and toss a match at him from behind?”-- in a way that Boris Karloff, Tom Tyler, and Lon Chaney Jr. never could, Lee makes the mummy seem genuinely threatening. It’s going to take a lot more than zillion-dollar CGI visual effects to make a mummy film that can stand up to this one.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact