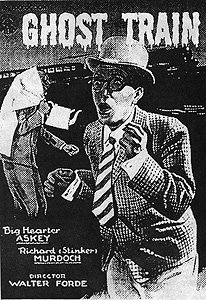

The Ghost Train (1941) *½

The Ghost Train (1941) *½

Some stories are so obviously iconic and so fruitfully adaptable to changing social contexts that it’s no wonder they get filmed over and over again. Then there are things like The Ghost Train, which seem sufficiently unpromising the first time around, and yet keep getting remade anyway. Originally a stage play by Arnold Ridley, The Ghost Train first made the transition to the screen as an Anglo-German co-production in 1927. A purely British version followed in 1931, the closest thing to a horror movie Gainsborough had released since Alfred Hitchcock’s take on The Lodger, and a 40-minute rendition was broadcast live on British television in 1937. (That’s right folks— the Brits had TV as early as 1937!) There were also a Dutch version in 1939, twinned Magyar- and Romanian-language versions produced by a Hungarian studio in 1933, and a kiddie-oriented Danish version as late as 1976. Limiting consideration for the moment to only those iterations of The Ghost Train made with some British involvement, there’s some indication that the silent version still exists, but good luck finding it. The Gainsborough talkie is in extremely fragmentary condition, with but five of the original nine reels surviving, and only two of those still possessing their sound elements. And precocious though the British may have been when it comes to television, it didn’t occur to them, either, to start recording their broadcasts until some ways into the 1950’s. As a result, anyone seeking to figure out what UK audiences found so perennially fascinating about Ridley’s fake-haunting comedy is limited, for all practical purposes, to yet a fourth version, the 1941 interpretation featuring music-hall and radio comics Arthur Askey and Richard Murdoch. Let’s just say that the mystery of The Ghost Train’s appeal seems likely to endure.

A bunch of mostly rather irritating people are traveling by train across the English countryside. The least obnoxious are professional sportsman R. G. Winthrop (Peter Murray-Hill) and his pretty, blonde cousin, Jackie (Carole Lynne). Winthrop is kind of a grouch, and Jackie can be just a little too perky for her own good, but if I had to share an train compartment with anyone in this movie, they’re the pair I’d pick. Ascending the ladder of unpleasantness from there, we have the slightly bumbling Dr. Sterling (Tower of Terror’s Morland Graham); stereotypical “funny” spinster Miss Bourne (Kathleen Harrison, from Night Must Fall and The Ghoul); Herbert (The Man in the White Suit’s Stuart Latham) and Edna (Betty Jardine), an appallingly dismal couple en route to their wedding and some manner of attendant showdown with Edna’s overbearing mother; and Teddy Deekin (Richard Murdoch— credited here as “Richard ‘Stinker’ Murdoch,” which should tell you a thing or two about the level of comedy in The Ghost Train), a man for whom schmuckery seems actually to be a profession. And then there’s Tommy Gander (Arthur Askey), fucktard of fucktards— a music-hall comedian and the living embodiment of everything that has ever not been funny in the British Isles. This guy makes Kay Kyser look like Lenny Bruce. He makes the Ritz Brothers look like the Kids in the Hall. I assure you, 30 seconds in his company, and you’ll want to murder him slowly with small, pointed objects heated to terrific temperatures. Our introduction to Gander comes when he yanks the train’s emergency stop cable so as to retrieve his hat, which blew off while he was gawking out the window like a large, stupid dog. This does not endear him to the ticket-taker and conductor, and it is some small consolation to imagine the fine Gander’s going to get slapped with as soon as his tour ends, and he stops moving long enough for the law to catch up to him. Next, Gander and Deekin take turns not endearing themselves to R. G. Winthrop by attempting to ensconce themselves in his compartment so as to flirt with Jackie. There’s some indication during this scene that Deekin and Gander know each other from somewhere, although there’s no apparent reason why they should. Finally, the train reaches the stop at which Gander, Deekin, Sterling, Bourne, the Winthrops, and the dim-bulb lovers have to get off and transfer, and everybody to whom we’ve been introduced lines up to join the We Hate Tommy Gander Club. The train is running a quarter of an hour late due to Gander’s stunt with the brake line, and they’ve all missed their connecting train as a consequence. What’s more, Saul Hodgkin the station-master (Herbert Lomas) informs the travelers that there won’t be another train to anywhere coming into this station until tomorrow morning.

But wait— it gets better. The train station is four miles from the nearest settlement, and there is no public transportation between the two points. Nor are there any accommodations to be had in that village four miles distant, beyond a couple of rooms at the pub. Also, the rain that broke out just as the train pulled up to the platform has escalated into a prodigious thunderstorm, effectively ruling out any attempt to walk into town. Nevertheless, Hodgkin refuses to let the stranded travelers spend the night in the station. His duties require him to lock the place up before he leaves each night, and no way in hell is he going to stay overnight there himself. Why not? Because of the Ghost Train, of course. There’s a disused stretch of tracks on the opposite side of the station from the active railway, and 43 years ago, there was a terrible accident on the old line. You see, a mile or two down from the station on the old line is a low-lying bridge with one of its spans on a turntable, allowing boats on the river below to pass through. Water traffic having apparently been more common than rail traffic at the time, that rotating span was kept open except when there was a train on its way. The station master in those days was Ted Holmes, an old man with a weak heart, and he died at his post at 11:00 PM one night with the overnight express only minutes away from the bridge. The ensuing crash killed everyone aboard but the conductor, and even he was never right in the head afterward. Ever since the tragedy, the ghost of that doomed train has periodically come tearing through on the old tracks at exactly 11:00 PM, and anyone who sees the phantom locomotive is said to die of fright on the spot. None of the travelers gives much credence to Hodgkin’s tale, but most of them find it strangely unsettling. Nevertheless, the impasse is broken in the only way it ever could have been, with Hodgkin riding off on his bicycle and the others shacking out in the station.

What follows is a long, grim period in which Tommy Gander mercilessly annoys everybody in a variety of supposedly funny ways. Incidentally, I’m pretty sure I now know what they’re going to do to me in Hell. Eventually (it only feels like eternity), Gander is interrupted by the return of Saul Hodgkin, who staggers his way down the platform (bicycle now nowhere in sight), falls through the main door when Winthrop opens it to see who is outside, and lands in the exact spot where Ted Holmes is said to have breathed his last. Dr. Sterling examines Hodgkin after the other men carry him into the office, and declares that he is dead. Then the weird girl shows up. Her name is Julia Price (The Terror’s Linden Travers), and she has a bug up her ass about the Ghost Train even worse than Hodgkin had. Evidently she can hear it from her bedroom whenever it goes by, and she invariably feels compelled to come and meet it. Julia is followed in rapid succession by her older brother (Raymond Huntley, from The Mummy and The Black Torment), who has come to haul her back home. The elder Price explains that Julia has been mentally disturbed since the night when she first thought she heard the spectral train, while Julia counters that her brother keeps her virtually a prisoner in the house they share. The subject of the Ghost Train raises in turn the subject of Saul Hodgkin, and Price demands to see the station master, even if he is dead. Hodgkin isn’t where the others left him, however, and just as Price and the stranded travelers are working up a really good head of steam for mutual recriminations, Julia blurts out that the reason for Hodgkin’s disappearance is that he wasn’t Saul Hodgkin at all, but rather the shade of the long-deceased Ted Holmes— the description she gives of Holmes matches alarmingly well, too. This all happens just a little before 11:00, and if only the bickering occupants of the station would look out the window, they’d see that something is coming fast up those tracks that haven’t been used since 1897, glowing eerily and making the most god-awful racket as it approaches.

Were it not for that damnable peckerwood, Arthur Askey, The Ghost Train might have been a reasonably entertaining— albeit timid and corny— film. As befits its mid-20’s origins, it ultimately explains away the supposed supernatural doings with a rational explanation easily a hundred times more implausible than any genuine haunting could be, this one specifically involving a coven of gun-running Nazi sympathizers. Gainsborough would probably have had a hard time getting any real malevolent ghosts past the British Board of Film Censors anyway, though, and both the flashback accompanying Hodgkin’s recounting of the legend and the scene in which the Ghost Train finally puts in its appearance are very effective within the limits of what the professional bluenoses would allow. Miss Bourne and the soon-to-be-weds are no more irritating than their counterparts in The Cat and the Canary, and considerably less so than those in The Bat Whispers. But then Askey comes along and fucks up everything. It’s no accident that he isn’t even present during the best two scenes in the film; his antics are toxic not only to any mood of horror or suspense, but even to the simple progression of the plot, and the one laugh he got out of me came by complete accident. (For the record, I had a little chuckle when Gander joked about teaching Miss Bourne’s African gray parrot to say “Heil Hitler.” This amused me because I once had a friend whose African gray really did pick up “Sieg heil!” from all the World War II documentaries she watched on the History Channel.) The strangest thing about the way Askey is used here is that all of the other characters consistently find Gander as insufferable as we do— he is presented not merely as a comedian, but explicitly as a bad comedian. So if he’s not funny, and none of the other characters (even fellow ass-clown Teddy Deekin!) think he’s funny, and the screenplay openly acknowledges his not-funniness at every turn, then why in the hell is he in this movie?!?! Wasn’t 1941 a little early for post-modern meta-humor in which the absence of laughs is itself supposed to be the joke somehow? Or was the British sense of humor already too advanced for its own good even in my grandparents’ day?

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact