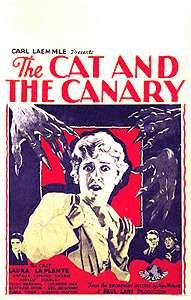

The Cat and the Canary (1927) ***½

The Cat and the Canary (1927) ***½

Many people consider James Whale’s The Old Dark House to be the ultimate spooky house movie. Ridiculous, I say. To see this sort of film done truly right, you have to forget about the talkies altogether, and go back to the mid-1920’s. After all, the spooky house mystery was well along the road to obsolescence by 1932, with little but parodies on the horizon in the future, but in the 20’s, in Hollywood, it was still the state of the horror-movie art. And with The Bat in 1926, Roland West proved how much life the genre still had in it, despite the ribbing he’d given it in The Monster the year before. It was in 1927, though, that the most enduring film of the bunch arrived, courtesy of Universal Studios and heavyweight German fantasist Paul Leni. Leni had established himself in his native land with films like Waxworks and The Mystery of Bangalor, earning a reputation as a visual stylist in the same league as F. W. Murnau or Benjamin Christensen. When he came to the United States (understandably signing on with a studio that was run by German immigrants like himself), he must have seemed like the perfect choice to beat West at his own game by snazzing up a dark house/colorful killer flick with nightmarish touches of German Expressionism. Assuming that was actually the intention, Universal boss Carl Laemmle got everything he could possibly have wanted from Leni’s adaptation of 1922’s monster stage hit, The Cat and the Canary. Leni took every one of West’s tricks and carried them even further, meshing them with a surrealistic European sensibility that must have floored even audiences that had turned out for The Bat.

A fast-moving prologue of title cards and highly stylized multiple exposure sequences establishes the death, after a long illness, of millionaire Cyrus West, attended by a swarm of grasping, avaricious relatives who all believed him to be mad. Perhaps he was, but the old man gets his revenge in the form of his will, which is to remain sealed for twenty years, and to which West has attached all manner of strange and onerous conditions. Not the least of these is that the will is to be read at midnight on the anniversary of West’s death, at the decaying mansion which for two decades has been occupied solely by the dead man’s ironically named housekeeper, Mammy Pleasant (Murder at Dawn’s Martha Mattox, who would play essentially the same role in The Monster Walks), and— if rumors are to be believed— the millionaire’s deranged ghost.

Roger Crosby, the executor of West’s estate (Tully Marshall, from The Hunchback of Notre Dame and The Mysterious Dr. Fu Manchu), is in for an unpleasant surprise when he opens the secret safe containing both West’s will and some other sealed envelopes pertaining to the bequest. There’s a live moth in the safe as well, and since no insect (save perhaps the queens of certain African termite species) could have survived for twenty years shut up in a metal box, that can only mean that somebody has been snooping around. And sure enough, the seals on the envelopes show signs of tampering. What makes this most distressing is that Crosby himself was supposed to be the only one who knew the safe’s combination. It certainly gives him much to think about as the heirs begin arriving.

The first on the scene is Harry Blythe (Arthur Edmund Carewe, from The Phantom of the Opera and The Ghost Breaker), followed rapidly by Charlie Wilder (Forrest Stanley, who would be almost invisible in Curse of the Undead 32 years later). The precise cause will never be revealed, but there is obviously a great deal of bad blood between the two men, who require considerable prodding from Crosby before they’ll so much as shake hands. Next come Susan Sillsby (The Haunted House’s Flora Finch) and her niece, Cecily Young (Gertrude Astor, who can be seen very briefly as an old woman in When Worlds Collide and The Devil’s Hand). No one in the family is more openly covetous or quicker to affront the memory of the deceased than Susan, while Cecily, despite her “liberated” flapper manners, is little more than a yes-woman for her overbearing aunt. Paul Jones (Creighton Hale, of Seven Footprints to Satan, whom the advent of the talkies relegated to a twenty-year succession of uncredited bit-parts in films like The Return of Doctor X), the youngest of the male heirs, seems at first to offer Susan stiff competition as The Cat and the Canary’s most irritating purveyor of comic relief, arriving as he does amid a flurry of tired old gags revolving around his cowardice and excitability. Finally, a few minutes past midnight, Annabelle West (Laura La Plante) puts in an appearance, providing the setup for Aunt Susan’s one genuinely funny line: “You’ve had twenty years to prepare for this meeting. It’s a wonder you couldn’t be on time!”

The will proves a crushing disappointment for nearly everyone. Old Cyrus West was not so far off his rocker that he didn’t notice the scheming of his would-be heirs, and out of arguably justified spite, he has bequeathed everything to the person who was too young at the time to take part in the chicanery. Annabelle West is now an extremely wealthy young lady, and the rest of the relatives don’t get diddly. But this being the sort of movie that it is, things are not quite so simple as that. Ever sensitive to the doubts the rest of the world held about his sanity, Cyrus has made Annabelle’s inheritance contingent upon her being judged of sound mind by a certain Dr. Ira Lazar (Lucien Littlefield, from One Body Too Many and Scared Stiff), who is supposed to be dropping by somewhat later. (Mind you, one might question the sanity of a psychiatrist who was willing to make house calls at 3:30 in the morning, but that’s a separate matter.) In the event that Lazar declares Annabelle to be of unsound mind, there is a fallback heir designated in a sealed letter that shared the safe with the will proper. Furthermore, Mammy Pleasant has a second sealed letter to Annabelle from her benefactor, which most likely reveals the hiding place of the West diamonds, which no one has seen since before the old man’s death.

But remember— somebody has already stolen a look at the will, and at the letter designating the alternate heir. This worries Crosby tremendously, for if the spy and the fallback heir were the same person, then Annabelle could well find herself in danger. Consequently, the lawyer takes Annabelle aside into the library, where he might reveal her possible competitor’s identity in private. But before Crosby has a chance to say anything, a hidden door swings open behind him, and a hairy, clawed hand drags him— and the letter— into a secret passageway. Because she was alone with Crosby at the time, the other relatives are reluctant to believe Annabelle’s bizarre story when she cries out for help, suspecting either that she imagined the disappearance, or perhaps that she herself caused it. The fact remains, however, that Crosby is nowhere to be seen in the house. Furthermore, a guard from the nearby insane asylum (George Stillman, of The Man Who Laughs) arrives right about then to inform everybody that there is an escaped maniac on the loose, and that he was last seen scaling the fence onto the West mansion’s grounds. This isn’t some harmless little loony, either. The way the guard tells it, this guy is a serial killer who likes to think of himself as a cat; the bodies of his victims were all mutilated as badly as any half-eaten canary. So in summation, we’ve got a fortune in hidden diamonds, a missing and possibly dead lawyer, a viper’s nest of back-stabbing wannabe heirs, and a psychotic murderer on the loose. Can this night possibly get any better?

From what I’ve seen, The Cat and the Canary is quite simply the finest spooky house movie ever made, and at this late date, it seems likely to retain its crown indefinitely. It isn’t for nothing that it would be remade just three years later as Universal’s first horror talkie (in both English- and Spanish-language versions), then again in 1939 as a Bob Hope vehicle for Paramount, and yet once more as recently as 1978— by which time its genre was otherwise represented solely by syndicated reruns of “Scooby Doo, Where Are You?” In plot terms, there is nothing to The Cat and the Canary that you can’t see in any other— or indeed, in every other— spooky house or colorful killer flick made between 1915 and 1945. None of the cast-members is anything but forgettable (except for Flora Finch as Susan Sillsby, whom you’ll wish you could forget). And perhaps inevitably, this movie is as heavily weighed down with god-awful comic relief as any comparable film this side of Sh! The Octopus (a movie in which the comedy is precisely the thing one wants relief from in the first place). Where The Cat and the Canary makes its bid for greatness is in the tremendous visual flair, and the attendant nightmarish atmosphere, which Paul Leni brings to what had become, by 1927, the horror genre’s first no-brainer, cookie-cutter formula. To the miniature models and weirdly stylized set design which Roland West had already used so effectively in The Bat, Leni added an array of Georges Méliès-like camera and processing trickery, turning The Cat and the Canary into probably the closest approximation of a German Expressionist horror film ever to come out of Hollywood. It’s one of the most authentically eerie-looking movies to come my way in quite some time, and if the Cat himself is a disappointingly minor presence (and a disappointingly silly makeup effect when we finally get to see his face), that shortcoming is easily counterbalanced by the sets and models for the West mansion, which becomes a figure of menace in its own right in a way that would not be matched, so far as I’ve seen, until The Ghoul six years later.

That emphasis on oppressive and unsettling atmosphere is one of the reasons why I think The Cat and the Canary, though billed in its day as a mystery, and conventionally described as such even now, is more properly considered a horror picture. The other concerns the unmasking of the villain, which happens not via deduction and entrapment on the protagonists’ part, but in the heat of battle between the killer and Paul Jones, who emerges in the end as a sort of reluctant hero. It’s a denouement that hearkens forward to the slasher movies rather than backward to “Murders in the Rue Morgue” or the writings of Arthur Conan Doyle, and mystery lovers are likely to find it most disappointing. On the other hand, those who have been waiting for the movie to cut loose with a physical threat to match its air of gloom and foreboding should be reasonably pleased with what happens when the Cat strikes at last— provided, of course, that they keep their expectations in line with the standards of 1927.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact