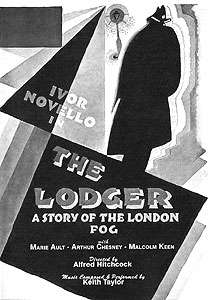

The Lodger / The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog / The Case of Jonathan Drew (1926) **½

The Lodger / The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog / The Case of Jonathan Drew (1926) **½

Considering that most of the films for which he’s known were made in the 1950’s and 1960’s, many casual viewers may be surprised to learn that Alfred Hitchcock’s career as a director stretches all the way back to the mid-1920’s. And while The Lodger wasn’t quite the first movie he made (there had been two others before it), it was his first thriller, and consequently the earliest Alfred Hitchcock Film in the sense of what most people think when they hear those words. Longtime fans will likely find it fascinating to see elements of the instantly recognizable Hitchcock style rubbing shoulders with the similarly distinctive tropes of the silent era. Everyone else will probably have something of a slog ahead of them, but no one with a serious, abiding interest in either the suspense genre or film in general should let that deter them from giving The Lodger a try.

It seems perfectly appropriate that the biggest name in suspense cinema should have gotten his start in the field with a movie inspired by the biggest name in serial murder. The Lodger may call its looming, shadowy killer “the Avenger,” but it is immediately obvious that we’re really dealing with Jack the Ripper. On each of the preceding six Tuesday nights, the Avenger has struck, claiming each time a young woman with curly, blonde hair. It is another Tuesday night as the film opens, and again, the Avenger comes out to keep his grisly appointment. And as is generally the case in these matters (at least in the movies), the police have as yet made no useful headway toward bringing the killer to justice.

That being so, I imagine the first thing we’re supposed to notice about fashion model Daisy Bunting (The Yellow Claw’s June Tripp, credited here simply as “June”) is her full head of golden curls. (I say “supposed to notice” because the English back then evidently had a rather looser definition of “golden” than we in the States use today. The monochrome film makes it impossible to be certain, naturally, but I’d have guessed that Tripp’s hair was more of a pale, reddish brown.) At least the girl isn’t on her own. Daisy lives with her parents (Arthur Chesney and Marie Ault, of The Monkey’s Paw), and her boyfriend, Joe (The Murder Party’s Malcolm Keen), is a cop. For that matter, her parents have recently decided to buttress their somewhat precarious finances by renting out the unused rooms on the top floor of their house, and the new lodger (Ivor Novello, whom Hitchcock also directed in When the Boys Leave Home, and who would revisit his present role when The Lodger was remade in 1932) has taken a liking to Daisy. If nothing else, she’ll have plenty of people looking out for her on Tuesday evenings.

The trouble is, Daisy might be better off if one of those people would keep his eyes to himself. The first thing the new lodger does when he moves in is to turn all of the paintings in his suite— portraits of pretty blonde girls with curly hair— around to face the walls. When Mrs. Bunting catches him doing it, he explains that the pictures get on his nerves, and asks her permission to remove them altogether. The lodger also brought no luggage with him except for a smallish leather bag like a surgeon’s satchel, and instead of unpacking it, he simply locks it away in the writing desk in his sitting room. When he goes out at night, he does so with a scarf pulled up over his face in exactly the same manner which the few living witnesses have ascribed to the Avenger. And most alarmingly, he has in his possession a street map of London, on which he has plotted the locations of all seven Avenger murders— the lot of them committed within a triangle of which his current abode serves as one of the vertices.

There are two events which set matters in motion toward their seemingly inevitable conclusion. First, Joe gets assigned to the Avenger case right about the same time that he notices how friendly Daisy and her new housemate have become toward each other. This, obviously, is a situation pretty much tailor-made for the abuse of police authority; the lodger would be in pretty big trouble even if there weren’t so much circumstantial evidence suggesting that he and the Avenger might be the same person. Second, Mrs. Bunting sees the lodger sneak out of the house on a Tuesday night, just in time to put him out on the streets during the hours in which the cops subsequently determine that Avenger victim number eight met her end. Before he knows it, the lodger is under arrest, and Joe and his men are turning the upstairs apartment over. The police find the map that plots the crime scenes, they find the lodger’s pistol, and perhaps most incriminating of all, they turn up a small leather portfolio containing a photograph of the Avenger’s very first victim. Even so, Daisy can’t believe that the man upstairs is a serial killer, and she distracts Joe for just a moment in the foyer of the Bunting house— long enough, that is, for the lodger to break away and make his escape. A bit later, she meets up with him to hear his side of the story: his sister was the first woman slain by the Avenger, and he’s been following the murderer’s trail ever since. But now that the cops are after the lodger, not only will they be diverted from the trail of the real killer, their activities will force the self-made vigilante to abandon his own pursuit for the foreseeable future. Oh— and did I mention that all this happens on a Tuesday night?

The Lodger was based on a novel by Marie Belloc-Lowndes. In the book (and in some of the numerous cinematic remakes), the Buntings’ lodger turned out really to be the Avenger. It seems to me that there are two reasons for the big change in this first film version. For one thing, though he’s quite obscure now, Ivor Novello was a big star in Britain during the 1920’s. Specifically, he was a singer/songwriter-turned-actor, and his stardom was of the variety that used to cause teenage girls to scream loudly and fall into swoons whenever he would appear in public. (By the way— I can’t tell you how much it gratifies me to see the marked decline of that annoying phenomenon during my lifetime. Sure, today’s teenagers still scream up a storm when they feel like it, but when have you ever seen some chick in the “Total Request Live” studio audience actually collapse into Carson Daley’s arms in a dead faint?) Given the circumstances of Novello’s fame, it would have seemed ridiculous to cast him as a murderer, just as it would be absurd to cast that guy who plays Clark Kent on “Smallville” as Jack the Ripper today. But there is another possible explanation, which doesn’t seem to have attracted as much attention. Hitchcock himself contributed to The Lodger’s screenplay, and that being the case, I think it significant that by making the lodger an innocent man persecuted by the authorities, this movie steps tentatively into the sort of Kafkaesque territory that Hitchcock would explore so much more thoroughly later in his career. The Lodger gives the subject rather short shrift, but you can almost feel Hitchcock springing to a higher state of attention whenever it surfaces.

You will note, however, that by talking of a higher level of attention, I am implying that the rest of the film is characterized by a less attentive sort of direction. That implication was entirely intentional. Much of The Lodger plays out like a standard silent-era melodrama, and those sections of the movie are frankly quite dull. True to his later form, Hitchcock tries to keep things interesting by playing lots of cool and innovative tricks with the camera (my favorite being the shot of the lodger pacing in his room, which was filmed from beneath a transparent glass floor so that the focus of the image is on the soles of Ivor Novello’s shoes), but again in keeping with subsequent Hitchcock productions, that kind of thing can carry the movie only so far. Hitchcock’s unusual approach to intertitles can also be as much a hindrance as it is a help. The expected dialogue cards are surprisingly rare. Instead, Hitchcock mostly employs his intertitles— often animated— to establish a mood, as with the Deco-style “Daisy” logo that precedes each of her entrances, or the neon sign-like “To-Night— Golden Curls” which serves as a sort of calling card for the Avenger. It’s a very imaginative way to dress up the look of the film, and the scarcity of dialogue cards does prevent the movie from becoming even slower than it already is, but there are a number of important scenes which non-lip readers will find it nearly impossible to follow.

What sticks in my mind most, however, is the rather jarring effect created by the mixture of Hitchcock’s highly inventive directorial technique and the rather rigid adherence on the part of the actors to so many of the silent era’s corniest conventions. While Hitchcock is piling on the asymmetrical frame setups and odd lighting schemes and multiple exposures, Ivor Novello, June Tripp, and Malcolm Keen seem to be vying to outdo one another with heavy-gauge histrionics. Even in the tightest of closeups, the players aim their performances at the non-existent back row. This, of course, is completely normal for a movie of this vintage, but because Hitchcock is so far ahead of his game, it calls attention to how far the cast is behind theirs. Modern filmmaking techniques like these demand more naturalistic acting; conversely, this sort of archaic stagecraft calls for more conservative direction. What we end up with in The Lodger is a movie that resembles an adolescent whose growth spurt has left him with mismatched features and limbs too long for him to control properly. Huge advances in some areas have far outpaced those in others, and the result is gawky, uncoordinated, and piteously covered with small but unsightly blemishes.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact