Trog (1970) -**˝

Trog (1970) -**˝

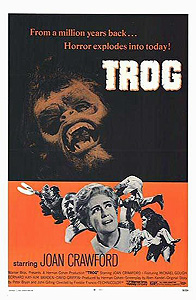

From the rise of Hollywood as the center of the American film industry until well into the 1980’s, there was one immutable truth about the movie business in the United States— no amount of fame was ever great enough to save you from monkeys. Maybe you’d meet them on your initial climb to stardom, or maybe you’d meet them on the way back down again. Perhaps they’d be real, or perhaps they’d be guys in rubber suits. They might be your comic sidekicks; they might be your antagonists’ hench-monsters; or if the gods were in an especially bad mood that day, one of them might even be your love interest. Indeed, it wasn’t totally out of the question that you’d end up playing one yourself. But regardless of the circumstances, you could be absolutely certain of at least this much in the course of your Hollywood career: sooner or later, there would be monkeys. Joan Crawford was able to put it off longer than most, but the monkeys finally came for her in 1970, when she wrapped up her five decades on the silver screen by headlining Trog for producer Herman Cohen. Cohen, incidentally, already had an established relationship with monkeys, for some ten years before, he had gone to Britain to make I Was a Teenage Gorilla, but wound up making Konga instead. Trog might perhaps be looked at as a second attempt to do something with the original idea, for it could just as well have been entitled I Was a Nanny to a Teenage Gorilla.

College zoology student Malcolm Travers (The Vampire Beast Craves Blood’s David Griffin) has gone on a spelunking excursion with his friends, Cliff (John Hamill, from No Blade of Grass and Girls Come First) and Bill (Geoffrey Case). The cave they’re exploring this morning isn’t on any map of the area that they’ve ever seen, and the dust and dirt on the floors inside show not a single trace of human footprints; so far as they can tell, it has gone completely undiscovered until now. There’s an underground stream in it, too, leading through a channel just wide enough for a single moderately sized man to negotiate it at a time. The impetuous Bill is the first to dive in to see where the stream leads. Cliff follows a short while later, but Malcolm himself sensibly insists on staying right where he is, so that there will be someone in a position to go for help in the event that the other two lads should get into trouble. That decision is even more sensible than it appears at first glance, for the trouble that greets Bill and Cliff in the gallery into which the stream empties comes in the form of some large, fierce, roughly humanoid creature, which mauls Bill to death and chases Cliff out of its lair, leaving him in a state of deep shock.

Malcolm’s first stop after dragging the semi-catatonic Cliff back to the surface is the nearby Brockton Research Center, run by his academic idol, the eponymous Dr. Brockton (Crawford, who’s a long way indeed from The Unknown— or even from What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?, for that matter). Travers figures the scientists will be able to help Cliff faster than any of the regular authorities (I advise that you swiftly abandon any attempt to figure out exactly what sort of research is normally conducted by Brockton and her colleagues), but the divergence from standard procedure makes for a rather stressful day for Malcolm. When Inspector Greenham (Bernard Kay, of Torture Garden and Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger), a detective from the nearest population center, responds to Brockton’s belated summons, he immediately leaps, for no evident reason beyond sheer pig-headedness, to the conclusion that Travers himself killed Bill. Greenham remains inclined to favor that interpretation even after Malcolm takes Dr. Brockton down into the cave, and she snaps a nice, clear, close-range photograph of the creature— which turns out to be sort of a burly, hairy man with a head like a baboon. Luckily for Malcolm, though, the scientist manages to wave Greenham’s stupidity in his face in a manner so obvious that not even he can fail to see it, and the emphasis of his efforts shifts from looking for evidence against Travers to figuring out ways to capture the thing in the cave.

Word spreads quickly, and by the time Greenham and Brockton have come to an agreement on how to proceed, the whole little town which both cave and institute orbit has become the center ring of an inglorious media circus. Alan Davis (David Warbeck, from Twins of Evil and The Beyond), a reporter for the local BBC affiliate, plops his camera crew down beside the mouth of the cavern while Brockton attempts to coordinate Greenham’s police into an organized search party, and neighborhood blowhard Sam Murdoch (Black Zoo’s Michael Gough, who had played opposite Crawford before in Berserk) arrives to talk the ears off of anyone who’ll listen, grumbling about how the whole thing is a hoax dreamed up by college kids who want to waste the taxpayers’ money. (It would appear that Murdoch is a figure of some power in the village, albeit not quite enough to make anybody bow to his ranting demands.) He’ll have to change his tune once the police frogmen enter the ape-man’s lair, and provoke him into storming up to the surface, smashing everything and everyone he can get his hands on along the way. Brockton, revealing for neither the first nor the last time that she’s the only person in the film who is capable of thinking clearly under pressure, shoots the creature down with a tranquilizer rifle, and arranges his transit to her institution.

From here on, the main conflict in Trog is between Brockton, who wants to study the creature from the cave, and Murdoch, who wants the ape-man killed. Brockton’s reasons are plain enough. Murdoch will be variously portrayed as a Christian fundamentalist who feels threatened by the irrefutable evidence of evolution that the living “missing link” presents, as a bigoted male chauvinist who resents Brockton’s position and authority in the community, and as a man so deeply in love with his own ignorance that he can’t abide anyone trying to deprive him of it, but the plain truth is that he’s just a dick. Brockton, with the aid of both Travers and her daughter, Ann (Kim Braden, later of Star Trek: Generations), attempts to teach and socialize the beast-man, much as one would a severely retarded child. She also brings in an international team of doctors and scientists, led by American surgeon Richard Warren (Robert Hutton, from The Vulture and Invisible Invaders), to perform medical and psychiatric experiments upon the creature, with the aim of enabling him to communicate more freely with his handlers. Murdoch, meanwhile, finagles the town magistrate (Thorley Walters, of Frankenstein Created Woman and The Earth Dies Screaming) into calling a court of inquiry on the subject of the ape-man, and launches an intrigue with Dr. Selbourne (Jack May, from The Yes Girls and Night After Night After Night), Brockton’s chief assistant, who seethes with envy and resentment at having to play second fiddle to a woman. When all Murdoch’s efforts seem likely to fail anyway, he breaks into Brockton’s lab and releases the protohuman after deliberately enraging him, reckoning that a monster rampage will get the townspeople, the police, and the rest of the local government to see things his way at last. He’s right, too, but he doesn’t live to enjoy his “vindication” for very long.

Sometimes nothing hits the spot like a really dumb movie that thinks it’s a pretty smart one. Trog is such a film. When Sam Murdoch turns the court of inquiry into a weird British reenactment of the Scopes trial, and director Freddie Francis turns Trog into a weird, monster-centric riff on Inherit the Wind, you realize that this movie nurses grand intellectual ambitions which it hasn’t a prayer of bringing to fruition. The constantly shifting grounds on which Murdoch opposes Brockton are the most believable thing in the film, in that they put his style of “reasoning” perfectly in line with that of real-world reactionaries, but Gough plays him as such an over-the-top prick that it becomes difficult to see the character as anything but a living, breathing straw-man argument. Meanwhile, it’s downright impossible to credit the movie’s stance in defense of science when its portrayal of scientists and their methods is so totally absurd, and when its creators so blatantly flaunt their comprehensive misunderstanding of every scientific field from medicine to anthropology to natural history to psychobiology. And that’s before we even attempt to come to grips with the visibly inebriated Joan Crawford’s performance as England’s foremost authority on no one’s really sure what!

Crawford was, within certain boundaries, unquestionably a fine actress. The part of an internationally respected scientist, unfortunately, was well outside those boundaries, and probably would have been even if she were sober. Throughout the film, it’s obvious that Crawford has little or no idea what the lines she’s been given to utter could possibly mean, and not just because Brockton’s pronouncements are invariably ridiculous and patently incorrect. The result is akin to acting by rote in a foreign language— the words just come spilling out as they stood on Crawford’s copy of the shooting script, her tone never altering until the scene moves on into more familiar territory. Of course, since that relatively familiar territory is more often than not something like Brockton teaching her pet ape-man to play catch with a rubber ball, it really doesn’t serve to elevate the situation any. Playing catch with a guy in the top half of a tatty ape suit was surely not the way Crawford envisioned herself going out, and it shows.

Yes, I said the top half of an ape suit. Specifically, it was the head, shoulders, chest, and back of an ape suit from 2001: A Space Odyssey, slightly re-dressed to disguise (or so I would imagine) the ravages of two years spent languishing in a warehouse somewhere. The effect is very strange. The head is beautifully designed and extremely expressive, but it’s in terrible shape, and it doesn’t seem to fit quite right. Furthermore, because the bodies of the 2001 Australopithecine suits were designed to be worn by the skinniest people Stanley Kubrick’s casting director could find, there was no hope at all of fastening any of the limb or torso pieces around Joe Cornelius’s beefy body. The chest and back (which were evidently permanently attached to the mask) therefore hang in loose and moth-eaten flaps like an ape-hide poncho, bearing no resemblance at all to the shaggy upper trunk they’re supposed to represent. It’s a real head-scratcher seeing this slightly mangy but still superb simian head sitting atop what is otherwise such a miserable and slack-assed costume. That Cornelius gives every indication of having taken the part of the ape-man fairly seriously just makes it all seem stranger still.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact