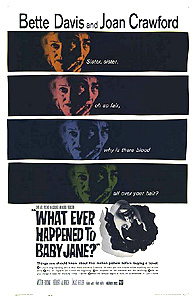

What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962) ***½

What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962) ***½

One of the best and most influential psycho-horror films of the 1960’s isn’t immediately obvious as a psycho-horror movie in the first place. When I first heard of What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?… oh, crap— 20 years or more ago now… it was presented to me as this campy melodrama about two old showbiz has-beens tormenting each other. And that’s an accurate description, as far as it goes, but the point is, it doesn’t go nearly far enough. It doesn’t begin to indicate the depth of loathing that the two sisters at the story’s core feel for each other, or the ingenuity that the dominant one displays in dreaming up ways to abuse and terrorize her utterly dependent sibling. Most importantly, it seriously undersells the gravity of the danger that the dominant sister poses, not just to her intended victim, but even to people not directly involved in the intrafamilial feud. The best way to explain to modern horror fans the strength of this movie’s credentials for inclusion within the genre might be to point out that Misery owes virtually its entire plot to What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?, although the motives and relationships of the principal characters are of course very different. Meanwhile, What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? was, like Psycho, the jumping-off point for a veritable industry of quickie copies— and a few of the rip-offs of each film were really rip-offs of the other in disguise. Indeed, it was one such crossover rip-off, William Castle’s Strait-Jacket, that finally revealed to me the profundity of Baby Jane’s impact upon the development of cinematic horror in the 60’s.

Before we can address the question posed by the title, we must first ask, “Who the hell was Baby Jane, anyway?” Well, back in 1917, Baby Jane Hudson (Julie Allred) ws a child star on the vaudeville circuit, singing and dancing to the accompaniment of music by her father, Ray (Dave Willock, from Queen of Outer Space and Revenge of the Creature). She was hugely successful, and made her parents quite wealthy. Alas, Baby Jane also understood perfectly well who really paid the bills in the Hudson household, and as her success went more and more to her head, she became the most appalling brat you can imagine. Jane’s egomania ended up deforming the whole internal dynamic of the family, not least because Ray was as cognizant as his daughter of economic realities. With Jane basically immune to discipline on account of her position as breadwinner, Ray tended to be doubly strict with her sister, Blanche (Gina Gillespie), in compensation. The girls’ mother, Cora (Ann Barton), did her best to ameliorate the resulting injustice for Blanche, but a certain amount of resentment was inevitable— and frankly, probably healthy.

Again, that was 1917. By 1935, though, the tables had turned in a curious way. Somewhere along the line, Blanche (now grown up into Joan Crawford) discovered a talent of her own. Other people soon discovered it, too, with the result that she became one of the hottest and most highly regarded actresses in Hollywood. Baby Jane, on the other hand… well, you know how it goes with child stars. Nevertheless, Blanche had taken to heart her mother’s admonition to do better by her sister than her sister did by her in the event that their positions were ever reversed. Blanche thus added to her contract a clause stating that for every Blanche Hudson vehicle put into production, the studio had to find a substantial role somewhere for Jane (now played by Bette Davis) as well. The execs were never happy about that, because the hard-drinking, truculent Jane was both a public-relations disaster waiting to happen and an exceptionally shitty actress, but if they wanted Blanche in their movies (and they did), a piggyback career for her sister was the price they had to pay. Then one night, a bizarre tragedy struck. Blanche was discovered lying in the driveway of the house the Hudson sisters shared, her spine apparently crushed by her own car. Jane, meanwhile, turned up in a nearby hotel, blackout drunk and unable to remember anything about what happened. The natural assumption was that Jane, mad with jealousy, had run her sister down and left the scene of the crime, but there were no witnesses to the event, and Blanche pressed no charges. Regardless, Blanche’s days on the silver screen were clearly over, and Jane’s along with them.

That brings us to “Yesterday.” The Hudson sisters still live together, all by themselves in a large but sensible house in Los Angeles. Blanche never regained the use of her legs, and it has fallen to Jane to take care of her all these years. Jane is still an angry drunk, seething with resentment over having peaked at eleven, and she habitually takes her toxic feelings out on the helpless Blanche. At this point, it’s fair to say that the two old ladies hate each other as only estranged sisters can, but there’s a certain equilibrium to their mutual detestation. Or at any rate, there is until one of the LA television stations acquires a package of Blanche’s old movies, and begins running them on weekend afternoons. It should go without saying that Jane’s cinematic oeuvre does not enjoy a similar renaissance, and she levels up from mean to positively crazy. Blanche can kid herself to some extent about her sister’s worsening condition, but there’s a limit even to sibling self-delusion. She quietly begins making arrangements to sell the house, and to commit Jane to the care of psychiatrist Dr. Shelby (Robert Cornthwaite, from Futureworld and The Thing). The trouble is, Blanche has not been nearly as clandestine as she believes. Jane makes a habit of reading all her mail (you better believe those fan letters from the TV station piss her off, too!) and listening in on all her telephone calls, so she knows full well what her sister is plotting. If Blanche thought Jane was nasty before, she ain’t seen nothing yet— and her two most likely outside allies, Elvira the maid (Halloween III: Season of the Witch’s Maidie Norman) and Mrs. Bates next door (Anna Lee, of Picture Mommy Dead and Jack the Giant Killer), may find coming to Blanche’s rescue decidedly hazardous to their health.

Meanwhile, Jane is working on orchestrating her own return to the public eye. She won’t be satisfied with the televised revival of her forgotten filmography, however. No, for Jane it has to be nothing less than a full-fledged comeback, which in her increasingly deranged mind means going back to her true heyday— the return not of Jane Hudson, but of Baby Jane Hudson. With that in mind, she places an ad in the newspaper calling for an experienced composer-performer to step into her long-dead father’s role in the act. That ad catches the eye of an ambitious but loutish musician named Edwin Flagg (Victor Buono, from The Evil and The Mad Butcher), and of his even slimier mother (Marjorie Bennett, of Billy the Kid vs. Dracula and I Wonder Who’s Killing Her Now?). Flagg recognizes from the moment he meets Jane that her comeback plans are a hideous, delusional travesty, but fuck it. It’s fine with him if some loony old broad wants to hire him for a project that will never, ever, ever get off the ground, just so long as he can get a few hundred bucks out of her up front. It may end up being fine with Blanche, too, since it means not only one more outsider coming round the house on a halfway regular basis, but also an outsider to whom Jane poses no credible physical threat. (Buono at this point in his life was not yet the man-mountain he’d later become, but he’s still got easily a hundred-pound advantage over Bette Davis.)

A funny, frustrating thing about these 60’s psycho-horror flicks— at least the ones made in the United States— is that none of them seem able to resist shitting the bed during the last five or ten minutes with a pointless twist, a “Dr. Obvious Explains It All” scene, or both. What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? is unfortunately no exception. I don’t want to go into detail, but the revelations of the final scene redefine the relationship between Jane and Blanche in a way that’s supposed to seem tragic, but really just makes an indecipherable mess of Blanche’s personality. Many people’s personalities are indecipherable messes, of course, but what we learn about the sisters and their secret history is just too big to be tossed off as a concluding whammy. It raises too many questions without leaving any time to answer them, so the effect is more Saw II than Planet of the Apes. At least Blanche gets to perform the accompanying back-story dump herself, rather than having the task delegated to a detective or a psychiatrist.

I’d imagine that when producer/director Robert Aldrich was developing What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?, he had Sunset Blvd. in mind at least as much as Psycho. Probably more, in fact. I mean, the whole subplot about Jane’s comeback scheme basically is Sunset Blvd., although it comes to a rather less grotesque conclusion. Similarly, I’m sure it never crossed Aldrich’s mind that he was helping to invent a whole new subgenre of psychological horror. But with Lukas Heller’s script (based on a novel by Henry Farrell), it would have taken a conscious effort on the director’s part to hold What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? within the bounds of mere showbiz melodrama. Simply put, Jane Hudson is too good a monster for that. Normally, Hollywood treated old women as vulnerable, pitiable, or comic figures. Even the traditional image of the witch exerted little pull on movies aimed at adult or general audiences— and Hollywood’s most famous witch, Margaret Hamilton’s Wicked Witch of the West, was conspicuously not old underneath her pointy black hat and pointier green nose. Then along came Baby Jane, the mad, murderous crone of a hundred Medieval fairy stories updated for the modern age, and within two years, there were legions of deranged old ladies scowling down from movie screens across the English-speaking world, not a few of them played by Bette Davis (The Nanny, The Anniversary) or Joan Crawford (Berserk, the aforementioned Strait-Jacket). Indeed, you might almost say that What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? initiated a decade-long full-employment program for female movie stars over the age of 50. An archetype so long neglected could hardly have failed to make such transformative impact, at least assuming that it was handled with any panache, and panache is exactly what Davis delivered here.

Not that Crawford isn’t impressive in her own way, but What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? is Davis’s movie through and through. Even when she’s supposed to be funny or merely irascible, as in Jane’s dealings with the proprietor of her favorite liquor store or nosy Mrs. Bates next door, Davis has an indefinable edge to her that says this woman is dangerously not right. And when she aims to be scary, she’s absolutely chilling. In one famous scene, Blanche finally works up the nerve to give Jane what-for, protesting to her sister’s face that she wouldn’t be able to get away with playing the petty tyrant if Blanche weren’t permanently confined to a wheelchair. Maybe you’ve seen it as a clip somewhere; it gets excerpted almost as often as the Psycho shower scene. Out of context, that confrontation is probably the main basis for this movie’s reputation as a classic of early-60’s camp. In context, though, it plays completely differently, with the emphasis falling not on the two women’s clashing histrionics, but on the dreadful matter-of-factness with which Jane dismisses Blanche’s concerns. “But you are, Blanche! You are in that chair!” she says, as if she were explaining the obvious to a very stupid child, refusing to engage the substance of Blanche’s grievance at all. A similar phenomenon is at work in the equally famous sequence where Jane serves Blanche her own dead pet bird (which had supposedly escaped while Jane was cleaning its cage earlier on) for lunch. What makes Jane so consistently terrifying is that there’s no passion to her mistreatment of her sister. There’s only a vast and ancient malice, totally in control of itself.

When Jane does lose control, it invariably has to do with either her mad comeback plans or her efforts to keep the recent escalation of her terror campaign against Blanche a secret. Both are fully believable exceptions to the rule, and both suggest that an unhinged Jane might be even worse than her usual, coolly sadistic self. That’s curious, because it’s also only when Jane loses her head that she becomes at all vulnerable or sympathetic. The seeming contradiction makes sense, though, because the manic Jane’s vulnerability is like that of a wounded weasel, and however much you might pity a wounded weasel, you sure as hell don’t want to get close enough to one to try comforting it. Notice that when Jane finally turns to murder, it’s panic that drives her; she kills when she realizes that, absent drastic action, her crimes against her sister are about to be found out. Meanwhile, there’s nothing scarier in this movie than the moment where Jane, all alone in the basement, recites a bit from her old stage act before a full-length mirror, and then screams in horrified rage at the haggard, puffy, wrinkled face looking back at her from the glass. It’s the fairy-tale witch thing again. Jane sees that the Fairest One of All sure as hell isn’t her these days, and that pisses her off.

Of course, there was one respect in which Davis didn’t need to act to portray Baby Jane. Neither, for that matter, did Crawford have to do any acting to put across part of her performance. There are a number of competing stories in circulation purporting to explain why— everything from competition over publicity to competition over the love of Franchot Tone to a snubbed lesbian advance supposedly made by Crawford in the early 40’s— but the point is that by 1962, Joan Crawford and Bette Davis hated each other every bit as much as Blanche and Jane Hudson, and had been at it every bit as long. The unfeigned animosity of the two stars accounts for much of this movie’s superiority over its numerous imitators. Not that actresses of their caliber couldn’t fake such a relationship for the camera, but the reality of the lifelong Crawford-Davis feud couldn’t help but bring something extra to any film where they play such bitter enemies. It also turns their casting into a publicity stunt worthy of William Castle, so it’s astounding that none of the big studios to which Aldrich initially pitched the project could see any value in it unless the two leads were replaced by younger and more popular stars. The bigger irony still is that Warner Brothers, the firm that most vehemently rejected What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? the first time around, ended up distributing it anyway, thanks to their partnership with Seven Arts (whose leaders understood what Aldrich was trying to do). Somehow I find it weirdly reassuring that studio execs in the old days could be just as epically clueless as their counterparts today.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact