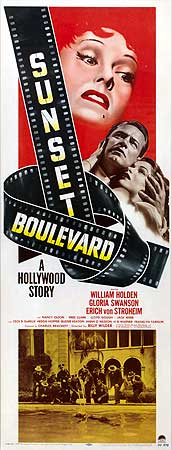

Sunset Boulevard (1950) ***½

Sunset Boulevard (1950) ***½

It’s important to remember, when discussing the first generation of film noir, that we’re talking about an artificial grouping imposed retroactively, by outsiders, upon a body of work whose creators never recognized it as a coherent movement, style, cycle, or whatever. The filmmakers who originated the noir style in the early 1940’s mostly saw themselves as studio hirelings, not visionary auteurs, and the movies now recognized as the founding documents of film noir were initially presented as more or less ordinary entries in a wide array of separate, long-established genres. They were mysteries, suspense thrillers, gangster pictures, melodramas, etc., and most of them were tossed off as quickie programmers besides. It was French critics, newly inundated with Hollywood product that had been kept from them by World War II, who first recognized that these disparate B-pictures had something important in common, and that that something needed a name. The “film noir” handle was bestowed in 1946, by Nino Frank and Jean-Pierre Chartier, although they weren’t quite the first to use it. Rather, they seem to have repurposed an old epithet once used by right-leaning cinema critics to tar movies they deemed morally dangerous. Given the new definition Frank and Chartier had in mind, that strikes me as perversely appropriate.

That piggyback quality (mystery but also noir, suspense but also noir, and so on) is part of the reason why I’m in the camp which holds that film noir is best thought of as a style or a mode rather than a genre unto itself. The other reason concerns the basic slipperiness of what constitutes film noir. It’s partly a look, typified by moody, highly stylized, black-and-white cinematography patterned after the horror movies of the early 1930’s, which had themselves been borrowing from 1920’s German Expressionism— but many noir pictures were shot in color, especially later on. It’s partly a setting, the crime-ridden underbellies of the big 20th-century cities— but rural noir and period noir exist as well. It’s partly a matter of characterization, invoking a world full of weary private eyes, sexually overripe women, and psychopathic criminals, none of whom can ever be fully trusted— but plenty of noirs get along fine without any of those types. And it’s partly a question of implied philosophy, a fundamental cynicism about human nature and institutions— which might be the one characteristic that truly unites all noir pictures. In any case, identifying film noir is a bit like using the DSM to diagnose mental illness. You match the movie’s symptoms against the list of noir signifiers, and if enough of them are present, then you can be reasonably confident that that’s what you’re watching.

Mind you, the situation became more complicated postwar, after the French started making film noir of their own. Many of those self-conscious French noirs made their way abroad, where they did enough business to inspire local copycats. Thus there’s British noir and Japanese noir and Scandinavian noir— plus even a little bit of German and Italian noir, although the style in those countries was quickly supplanted by Krimi and giallo respectively. And of course there was a new wave of Hollywood noir that imitated the immitations, frequently without seeming to realize that they had borrowed from American models in the first place. Then at some point, the criticism of Frank, Chartier, and their contemporaries gained traction outside of France, too, and an international cycle of fully self-aware film noir appeared. There seems to be surprisingly little agreement on the precise chronology, however, which makes it a bit tricky to get a handle on films like Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard. A baroquely weird and twisted tale of showbiz insanity, narrated from beyond the grave by a hard-boiled grifter whom we meet as a corpse floating in a madwoman’s swimming pool, Sunset Boulevard is slyly self-aware on many levels, but it came early enough that one can plausibly question whether Wilder would have understood himself to be making a noir.

The aforementioned floater used to be Joe Gillis (Damien: The Omen II’s William Holden). Joe was a writer when he was alive— first a reporter for some Dayton, Ohio, newspaper, then an author of short stories, and finally a freelance screenwriter in Hollywood. Mind you, he never enjoyed serious success in any of those fields, and he picked a uniquely bad time to break into the last one. I’ll explain later. What matters right now is that Gillis found himself over $200 behind on his car payments— enough to get a couple of repo men on his case. A visit to his producer friend at Paramount (Fred Clark, from Eve and The Curse of the Mummy’s Tomb) availed him nothing. Nobody at the studio liked that baseball script Joe sent in a month or two ago, and there wasn’t so much as an “additional dialogue” gig available in the current production schedule. Joe’s agent (Lloyd Gough) was no help, either. Hell, Gillis couldn’t even bum a loan bigger than 20 bucks from his assistant director buddy, Artie Green (a preposterously young-looking Jack Webb). He was all set to chuck everything and go back to Dayton when a car chase against the repo men forced him to hide out in a long and heavily overgrown driveway off of Sunset Boulevard, up in the hills where the old-timey Hollywood royalty used to live. At the end of that driveway was a decaying mission-style mansion, surely a monument to the swollen ego of some silent-era movie star, or maybe even the head of some defunct studio. You can imagine Joe’s surprise when a voice rang out, announcing despite all appearances to the contrary that the old house was still inhabited.

The owner was Norma Desmond, forgotten starlet from who knows how many of Cecil B. De Mille’s epics of the teens and 20’s (Gloria Swanson, who really did make a bunch of movies for De Mille on her way to the likes of Nero’s Mistress and Killer Bees). She lived alone apart from her surly German butler, Max (Erich von Stroheim, from The Crime of Dr. Crespi and Unnatural), and a tame chimpanzee. Or at any rate, she had the chimp up until recently. The latter was the cause of some mordant hilarity at that first meeting between Joe and Norma, because the ape had just died, and both of the mansion’s human occupants mistook Gillis for the undertaker who was supposed to come round with an appropriately sized coffin. Joe explaining the real situation ought to have been the end of it, but when Miss Desmond heard that word, “writer,” it fired up some of the dusty old machinery in her head. She’d been working on a script of her own, you see, an epic of the ancient world such as she used to star in when she was young, and she wondered if maybe Joe would mind taking a look at it. Was that opportunity Gillis heard knocking? You bet it was! Sure, the old lady’s screenplay was trite, unstructured, repetitive crap, but it was also grand crap of a sort that might pose an interesting challenge to someone used to writing on a more modest scale. But more importantly, Norma Desmond was so fucking rich that Gillis could inflate his asking price to the ceiling, and she’d never bat an eyelash. A week’s work, maybe two, and he’d be able to square up with the bank, tell the repo men where to stick it, and have enough left to tide him over until his job prospects improved. He wouldn’t even have to care whether or not any of the studios wanted to buy the stupid script!

What Gillis didn’t figure on was that people like Norma Desmond are accustomed to getting their way, and to not much caring whether their way is compatible with anyone else’s. The first red flag went up when Norma paid off Joe’s apartment and moved him into the spare room over her garage (all without telling him, you understand), ostensibly so that she could more closely supervise his work typing up and revising her screenplay. Then she started buying him stuff— clothes, jewelry, a swank gold cigarette case, you name it— even as she refused to front him $200 when the repo men finally caught up to him and came for his car. Before Joe knew what hit him, he was a kept man, and on New Year’s Eve, Norma let him know in no uncertain terms that she intended to keep all of him. His one respite from the increasingly intolerable situation was, oddly enough, another collaborative writing project with a woman. Artie Green’s fiancee, Betty Schaefer (Nancy Olson), was a reader for Paramount— in fact, it was her dismal verdict that really killed Joe’s baseball script— but she wanted to move up to writing. As it happened, Betty was a fan of Joe’s short fiction, and she pressed him to go halvesies with her on turning one of his old stories into a screenplay. The trouble was, the pair soon found themselves falling for each other— and we already know there was no happy ending for them, don’t we?

Watching and reviewing Sunset Boulevard is something of a milestone for me. Until now, I’d never seen a movie directed by Billy Wilder— but I’ve seen a bunch of stuff by his no-talent brother, W. Lee. To put that in possibly more accessible terms, it’s like finally seeing Rocky only after absorbing the complete works of Frank Stallone, or Apocalypse Now only after becoming a self-taught authority on the films of Joe Estevez. I wonder if I might actually have appreciated this movie more for having Killers from Space and The Snow Creature as my baseline for comparison?

Either way, I found Sunset Boulevard highly enjoyable. I do suspect, however, that some would accuse me of watching it “wrong.” While I recognize and appreciate it as a dense meta-commentary on the convulsions that wracked Hollywood at the turn of the 50’s— and we’ll talk about that in a bit— where Sunset Boulevard really captures my interest is in its capacity as a missing link between film noir and 60’s psycho-horror. Most noticeably, Gloria Swanson’s Norma Desmond is the ur-example of faded Hollywood glamour queens roaring back onto the screen as deranged harridans. Long before Bette Davis and Joan Crawford turned over-the-hill ex-starlets into a temporarily hot commodity, Swanson’s performance here gave them a model on which to build. She was the first to risk burning her former public image to the ground by saying screw beauty, screw charm, screw sex appeal, and by playing a nasty, twisted hag with all her heart. (Although, if it makes her feel any better out there beyond the grave, Swanson visibly had to work much harder at being repellant than her imitators in the 60’s and early 70’s. Norma Desmond’s age and appearance are far less of a deterrent than her arrogance, narcissism, and insanity.) Nor was it just the actresses in those later films taking notes. Victor Buono’s subplot in What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?, for example, couldn’t be any more transparent a copy of Sunset Boulevard.

The other ways in which Sunset Boulevard ties noir to the spawn of Psycho are more instructive, however. The tyrannical, emasculating domination that Norma exerts over Joe and Max (whose relationship with his employer is ultimately revealed to be just as bent in its own way) makes her an obvious precursor to Ma Bates as well as Baby Jane. There’s a bit of Baby Jane’s sister in here, too, visible in the way Norma uses her emotional fragility as a weapon of blackmail, while her Cougar from Hell persona prefigures a different Crawford performance, the sexually predatory carnival owner in Berserk. The men, too, point the way toward the future, although Joe and Max bear up considerably better under the weight of their shame and self-disgust than would most of their counterparts in true psycho-horror. Had this movie been made in 1964 instead of 1950, one or the other of those guys would almost certainly find himself murdering Norma’s enemies in a deranged bid for her affections. Note, however, that abnormal psychology was a big part of the noir formula as well— indeed, that’s the point I’m trying to make. Sunset Boulevard reveals that noirish concerns had a much stronger influence than is usually credited upon the development of the horror genre once audiences decided that psychopaths were at least as scary as vampires.

Of course, Sunset Boulevard’s creators had even less way of knowing that than they had of realizing they were making a landmark of film noir. Their contemporary perspective is best encapsulated by the tagline that graced most of the movie’s promotional artwork: “A Hollywood Story.” It’s difficult to overstate the turmoil in which the American movie industry found itself at the turn of the 50’s. It faced unprecedented competition from television, its major players were hamstrung by an increasingly obsolete and out-of-touch code of self-censorship, and the Supreme Court had just ruled that the entire Hollywood business model was built upon flagrant violations of federal antitrust law. The studios’ response to those challenges— to concentrate their resources on the production of fewer, bigger pictures— put countless jobbing writers and directors out of work, as there simply weren’t enough films being made to keep them all occupied. Eventually, much of that displaced talent would find homes with the new crop of independent production companies that sprang up to fill the content vacuum left by the contraction of output from the majors, but in the meantime, the result was an impossible job market and a sharp curtailment of opportunities for career advancement. Meanwhile, it was coming to people’s attention that Hollywood had a long history of doing conspicuously wrong by people whose days had come and gone. Most directly relevant to the genesis of Sunset Boulevard was the fate of D. W. Griffith, who did as much as anyone to put the Los Angeles movie colony on the map, but died forgotten in 1948 after a seventeen-year retirement. One of the very few attendees at Griffith’s funeral was producer-screenwriter Charles Brackett, a friend and frequent collaborator of Wilder’s, who was moved to begin work at once on a script that would shine some light on the shabby treatment that had become practically the norm for ex-stars.

What we end up seeing in Sunset Boulevard, then, is both a dramatization of the industry’s midlife crisis and a juxtaposition of it against the similarly huge disruption created by the talkies 20 years earlier. Norma Desmond’s crazed determination to live in a dead past is the natural result of her being offhandedly discarded after a youth in which she was treated like divinity. Joe Gillis’s transformation from ambitious writer to self-hating gigolo is driven as much by his inability to find steady, paying work within the implosively contracting studio system as it is by his fatal underestimation of Norma’s strength of will. And Max stands revealed in the end as an artist so thoroughly bewitched by the glamour of Hollywood that he nuked his own career in order to stay close to it. The only character who can function in this mad and toxic environment is Betty Schaefer, the set-builder’s daughter, who was literally raised in it. It’s a remarkable thing to see a team as gifted as Wilder and Brackett look this long and hard at the source of their own livelihoods and conclude, “Man, fuck this business,” before getting right back to work like nothing had happened.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact