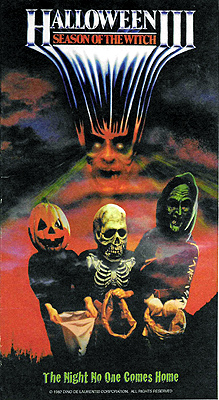

Halloween III: Season of the Witch (1982) -**½

Halloween III: Season of the Witch (1982) -**½

Halloween II was by no means the megaton-yield blockbuster that its predecessor had been, but it still made plenty of money. Furthermore, it made plenty of money at the moment when it was first becoming apparent that the 80’s would be a huge decade for sequels. A Halloween III was therefore inevitable. However, John Carpenter and Debra Hill had found it difficult enough to contrive just one continuation of the original story— and they’d ended Halloween II by blowing both Michael Myers and Dr. Loomis to kingdom come. Where the fuck were they supposed to go from there? Carpenter’s idea was that the third film wouldn’t continue the story at all. Rather, it would shift the series in a hitherto untried direction, with a new, free-standing horror movie on the theme of Halloween to be released each October until audiences finally got sick of them. And with no connection between the individual entries beyond being set on or around October 31st, it could be possible to spin such a franchise out indefinitely. It’s almost impossible to overstate what a wild scheme this was in 1982. Today’s audiences— today’s horror audiences especially— are well accustomed to in-name-only sequels, but back then there was very little precedent. And if we disregard the odd one-off (like The Return of Doctor X), and limit the field strictly to ongoing series, the only things slightly similar to Carpenter’s new vision for Halloween were Universal’s largely forgotten “Inner Sanctum” mysteries from the 1940’s and the American International Pictures Poe cycle from the 1960’s and 1970’s. Irwin Yablans and Moustapha Akkad, the men who held the Halloween purse strings, took some convincing (indeed, Yablans never got fully behind Halloween III, doing no more than to authorize continued use of the franchise name in exchange for a cut of the profits), but Carpenter was by that point someone whose instincts about horror movies it made sound financial sense to trust.

Besides, there was some serious talent lining up behind the project. Joe Dante was attached to direct, and he somehow persuaded Nigel Kneale (whose Quatermass trilogy made him something of a hero to Carpenter) to write the script. Kneale was a perfect match for Hill’s notion that Halloween III should hinge on the malign intersection of modern science and ancient magic, and Dante was at exactly the right point in his career to be looking for bigger and better things to move on to from New World Pictures. Unfortunately, Dante had to back out early in the film’s development, and Kneale’s script struck Carpenter as out of touch with the tastes of the modern horror audience. Carpenter gave it a polish with an eye toward intensifying the violence and bloodshed, and in doing so irritated Kneale so badly that he disowned the resulting draft and refused screen credit. The revised script didn’t suit replacement director Tommy Lee Wallace, either, and he gave it a rewrite of his own before filming commenced. If this is starting to sound to you like one of those Troubled Productions, you might be on to something. You know how those tend to turn out, too, don’t you?

It’s the night of Saturday, October 22nd, and a frazzled-looking man (Al Barry, from Re-Animator and The Last Starfighter) is being chased by a team of coolly efficient, unsettlingly businesslike assassins. As absurd as this sounds, the killers seem to be after the cheesy latex Halloween mask stuffed into their quarry’s pocket. Badly banged up and ranting incoherently, the hunted man eventually winds up in the hospital, under the care of Dr. Daniel Chaliss (Tom Atkins, of Escape from New York and Creepshow). He dies in Chaliss’s care, too, but not because of anything the doctor does or fails to do. One of the assassins (Dick Warlock, from Pumpkinhead and The Abyss) infiltrates the hospital and finds the room where Chaliss sent his patient to enjoy a healing thorazine nap. After dispatching the target in a way that really doesn’t look as though it should be fatal, the killer calmly strolls back to his car, sits down behind the wheel, pours a five-gallon can of gasoline over his head, and blows himself and the vehicle to smithereens with a cigarette lighter. The fire is so intense that by the time it burns itself out, there’s nothing left inside the charred hulk of the car but ashes.

With all that going on, it’s tempting to ignore a pair of items that appear on various televisions in the background. Don’t do that, though, because they, even more than the fate of Chaliss’s unfortunate patient, point to what this movie is really about. One of those bits of televised flotsam is a very peculiar story on the late news: somebody has stolen part of Stonehenge! We’re not talking about some random bit of rubble, either. Rather, the stolen piece is one of the lintels from the outer ring, 5000 goddamned pounds of solid dolerite. Needless to say, it’s a mystery how the theft was accomplished. The other thing for which you should be monitoring the incidental TVs partially explains the mask in the victim’s pocket. It’s a commercial for Silver Shamrock Novelties’ “Big Halloween Three,” a trio of crappy and unimaginative latex masks that we’re expected to believe have become the hottest thing this year among the trick-or-treat set. Although there’s a legitimate possibility of the Stonehenge business either slipping your mind later or slipping by you in the first place, there isn’t a chance in hell you’ll miss the Silver Shamrock ad— not least because you’ll see and/or hear it about 31,000 times before the movie is over. The jingle is by far the most diabolical thing about Halloween III, too, sure to haunt your dreams in a way that none of the film’s ostensible scares ever approach. As a peppy, electronically synthesized sound-squiggle boobles inanely underneath, the chipmunk-pitched voice of Tommy Lee Wallace sings (to the tune of “London Bridge Is Falling Down”), “[x] more days ‘til Halloween, Halloween, Halloween; [x] more days ‘til Halloween— Silver Shamrock!” It’s excruciating.

Anyway, Dr. Chaliss can’t shake the uneasy feeling he’s left with after his weird, hard night at the hospital, no matter how much he drinks, avoids his ex-wife (Nancy Loomis, the only member of the Halloween III cast to have appeared in both Halloween and Halloween II) and children, or flirts with women half his age. Luckily for him, one of those inappropriately young ladies is Teddy (Wendy Wessberg), an occasional girlfriend of Daniel’s who works for the local coroner, so he’s got at least a few resources in his search for a way to explain the lurid crime. Teddy agrees to keep him apprised of whatever she learns from the charred remains of the assassin’s car, even though she isn’t supposed to share such information with anyone not officially assigned to the case. An even better avenue of investigation opens up on Friday the 28th, when a girl called Ellie Grimbridge (Get Crazy’s Stacey Nelkin) accosts Chaliss at his favorite bar. Ellie turns out to be the daughter of the dead man. She explains that her dad owned a toy shop, which makes him sound like just about the last person anyone would undertake a kamikaze mission to kill. Chaliss can’t offer her much additional insight now, but if she’s serious about getting to the bottom of the mystery, he can grab a six pack, blow off his family once again, and play Hercule Poirot to Ellie’s Miss Marple.

The pair head first to Ellie’s father’s store, where the garish display rack for the Silver Shamrock Big Halloween Three first catches Daniel’s attention, then reminds him that Grimbridge was carrying a Halloween mask when he arrived at the hospital. Specifically, he was carrying the Silver Shamrock jack-o-lantern mask. Then Ellie observes that the last entry in her dad’s daily planner is a notation about driving out to Santa Mira— where Silver Shamrock Novelties has its factory and headquarters— to buy more of the fast-selling masks. That was the day before he was killed, so Ellie and Daniel figure a trip of their own is in order.

Neither would-be sleuth really has a plan at that point, but one starts to take shape when it becomes apparent that Santa Mira is for all practical purposes a company town these days, with virtually every one of the inhabitants either directly or indirectly on the Silver Shamrock payroll. Chaliss will pose as Grimbridge’s business partner, attempting to track down the shipment of Halloween masks that Grimbridge was supposed to have bought last Friday. He and Ellie (posing as Daniel’s wife) get a room at the motel run by the ineffably shifty Mr. Rafferty (Michael Curry, from Dead & Buried and The Philadelphia Experiment), and make arrangements to tour the Silver Shamrock plant as part of a group of “fellow” toy vendors. Silver Shamrock boss Conal Cochran (Dan O’Herlihy, of Invasion U.S.A. and RoboCop) is charming enough as he shows the visitors around his factory, but there’s something forced and furtive about his demeanor just the same. Also, there’s one section of the facility that’s off limits to the tour group— even to Buddy Kupfer (The Beastmaster’s Ralph Strait), the top-selling Silver Shamrock retailer in the country— and the excuse offered by Cochran to explain the interdict holds no fucking water at all. Even that isn’t half as suspicious, though, as the garage behind the factory, where Ellie plainly sees her father’s station wagon gathering dust. And even that isn’t half as suspicious as the factory’s security guards, several of whom look exactly like the guy who killed Ellie’s dad.

The most damning clue of all, however, is discovered by Marge Guttman (Garn Stephens), the saleswoman staying in the room next door to Daniel and Ellie’s. Not that the discovery does her any good, mind you. She had brought along an example of defective merchandise, a jack-o-lantern mask from which the Silver Shamrock trademark medallion had come detached. Marge never did get a chance to show the thing to Cochran, and that night in her room, she notices that the medallion has a circuit board, of all things, cut into the reverse face. As she pokes at the anomalous electronics, she accidentally triggers one of their functions. A beam of blue light shoots out, and blows off the lower half of the unfortunate woman’s face. Then a huge, fat Jerusalem cricket inexplicably crawls out of the smoldering hole that used to be her mouth.

Ellie is too busy succumbing to Daniel’s irresistible sexual dynamism (roughly equivalent to the irresistible sexual dynamism of Joe Don Baker or Bo Svenson) for either of them to notice the brief commotion next door, and only the arrival of an ambulance (presumably summoned by Rafferty) alerts them that something has befallen Marge. The paramedics are unmoved by Chaliss’s medical credentials, brushing him aside as they would any other bystander. Conal Cochran (whose limousine pulls up out of nowhere the moment the tailgate on the ambulance closes) gets more deference, however. He assures the small crowd which has gathered by this point that the clinic at the factory is equal to any hospital that Ms. Guttman might plausibly be sent to instead, but that’s hardly enough to allay Daniel and Ellie’s mounting suspicions— especially not after Chaliss overhears one of the paramedics telling Cochran that Marge was caught by a “misfire.” Just the same, the situation has turned threatening enough to make the two interlopers lose their taste for amateur detective work. They decide to leave Santa Mira at once, but alas for them, Cochran is too close to zero hour now for anyone who might suspect anything about his plans to be allowed to leave.

Okay, but what the fuck is Cochran planning? Halloween III: Season of the Witch comports itself as a mystery, which would normally mean that I’m not telling you shit about that. However, since the utter lunacy of the scheme is the only enjoyable or even faintly interesting thing about this movie, I shall go right ahead now and spoil the surprise. Silver Shamrock Novelties is really a front for some kind of neo-Druid pagan cult, of which Conal Cochran is the high priest. It was they who stole that piece of Stonehenge in order to harness the monument’s magical properties to power a mass misdeed defying any possibility of belief. Each Silver Shamrock Halloween mask contains a circuit board like the one Marge discovered, and each circuit board incorporates a minute particle of Druidically sanctified dolerite cut from the Stonehenge block. On Halloween night, the final broadcast of That Damn Commercial (which millions of kids are sure to be watching, because it’s supposed to include the name of a sweepstakes winner, and is scheduled to air at the end of the Halloween Horror-Thon which the company sponsored on one of the networks) will trigger the chips inside all the masks within earshot of a television set. The result, as Marge could guess if she were still alive to, will be the grandest and most glorious Samhain hecatomb of all time. That’s all well and good (or well and evil), but you might nonetheless ask what all this rigmarole is meant to accomplish for Cochran and his followers— Chaliss certainly does. The old Druid’s answer will make you either stand up and applaud the sheer, brass-balled gall of this movie, or hurl the nearest suitable object at the screen.

In theory, I’m intrigued by Carpenter’s vision of a thematically unified, anthological film franchise, but in practice, the time to play that card within the context of the Halloween series was in 1981, when the first sequel was being developed. Once Michael Myers had two successive films under his belt, any subsequent offering called Halloween [X] was his rightful property forevermore. Maybe— maybe— the fanbase would have grudgingly accepted a sequel about a copycat killer instead, but no way were slasher fans going to swallow a paranormal conspiracy thriller masquerading as a Halloween movie. Anyone (except, apparently, for John Carpenter, Debra Hill, Moustapha Akkad, Dino De Laurentiis, and Tommy Lee Wallace) could have predicted that Halloween III: Season of the Witch would be greeted with an outraged chorus of “What the fuck even is this shit?!?!”

This is the point at which I’d like to be able to say something like, “however, if you can put your franchise-based expectations aside, Halloween III is a pretty decent example of what it’s actually trying to be.” I’d like to be able to say that, but it simply wouldn’t be true. Indeed, if you start instead with the expectations engendered by “Nigel Kneale does The Wicker Man by way of The Parallax View,” then this movie looks, if anything, a great deal worse. The secret to making a good conspiracy thriller is that the conspiracy itself must be believable. It doesn’t have to be realistic, strictly speaking, but it does need to have a clear motive, an internally plausible methodology, and an intelligible relationship between its means and its ends. Halloween III fails on all counts. The conspirators of Silver Shamrock have literally no motive at all that is ever elucidated within the film itself. To be sure, there are several motives which we might impute to them without contradicting the letter of the text, but at that point, we’re doing the filmmakers’ work for them, under conditions that offer very little gain for it. As for methodology, I’m prepared to grant a great deal of license at the intersection of mad science and black magic. I’ll even grumble only a little when whichever writer was responsible for this detail tries to hand-wave the theft of a Stonehenge lintel the way Carpenter and Hill once hand-waved Michael Myers’s ability to drive a car. But I can’t accept on any level that Silver Shamrock’s cheesy and unimaginative Big Halloween Three are the best-selling bits of Halloween paraphernalia on the market this year. It’s 1982, for fuck’s sake! If you want to sell to kids on the scale that Conal Cochran aspires to, you need tie-in media— a comic book at the very least, and preferably a Saturday morning or weekday afternoon cartoon. Silver Shamrock has nothing but a commercial so annoying that not even the target audience would be able to tolerate it more than once or twice. And with regard to rational connection between ends and means, notice that the best possible outcome to Cochran’s scheme— the best possible outcome for Cochran and his followers themselves!— is failure due to mass equipment malfunction. Imagine for a moment that the plan succeeds, and millions of children across America have their heads turned to writhing masses of snakes and bugs by the magitech gizmos in their masks. Everyone knows who made, distributed, and sold those masks. Everyone knows who bought the TV airtime for the commercials, and who sponsored the Halloween Horror-Thon that broadcast the trigger signal during its final commercial break. The stolen Stonehenge lintel is sitting right there in the basement of Cochran’s factory in Santa Mira. All Cochran could imaginably stand to gain from the whole stunt as presented is a swift and terrible retribution.

All that said, I have come to appreciate Halloween III as an explosive collision of bad ideas and an exercise in cinematic tomfoolery. Beyond all the beautifully dumb things that it asks us to accept for the main story to work, beyond the unconscionable repetition of the insidious Silver Shamrock jingle, beyond the outrageous effrontery of passing itself off as a sequel to Halloween in the first place, Season of the Witch is a film that dares to be its own worst self in every way it can. Consider the whole second act, built around the tour of the Silver Shamrock plant, when Halloween III reinvents itself for a time as a cheap and witless version of Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory. Apart from Ellie, everyone involved is some cartoonish species of Ugly American, leaving me in little doubt that this section at least was carried over more or less intact from Nigel Kneale’s draft. Assuming I’m right, what the hell was Kneale thinking? He was usually much more reliable than that! Consider also the overstuffed action-movie climax, with its inimitably De Laurentian combination of epic conception and tawdry execution. Most of all, take some time to contemplate Our Hero, Dr. Daniel Chaliss. I haven’t said much about him as a character, because his personality exists in weird isolation from the business of stopping a neo-Druidic mass-child-murder plot, but the guy truly is something else. A drunk and a womanizer and an irresponsible father, he ought to be fairly loathsome even before he climbs into bed with a girl more than 20 years his junior. But there’s something about his manifest incompetence at life that’s as endearing as it is exasperating, as if Chaliss were some manner of very large and dim-witted, but friendly and eager-to-please dog. Note, however, that this is a totally separate matter from the believability of Ellie falling for him the way she does. The only way I can figure it is that Debra Hill herself must have had a thing for Atkins, because this is the second time he was cast in a John Carpenter movie as a cradle-robbing lothario, despite everything about him screaming “little league baseball coach” or “construction site concrete-pouring foreman.” I’ll give Atkins this, anyway: he’s undeniably the right everyman hero for the stupidest conspiracy thriller of the early 80’s.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact