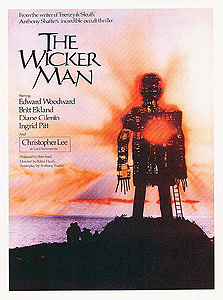

The Wicker Man (1973) *****

The Wicker Man (1973) *****

It’s weird how little congruence there can be between significance and success. Sure, most important movies acquire their importance precisely because they make a ton of money, and in doing so launch careers, inspire rip-offs, or even define (or redefine) entire genres, but sometimes it isn’t that simple. Some movies make a difference gradually, accruing more respect than box-office revenues, and find their audiences slowly, over many years, through the proselytizing of fans and critics. Their imitators— and these films are imitated, albeit rarely by enough people at a time to constitute a trend— are drawn to them not by the smell of profit, but by the promise of a fertile idea which no one film can begin to exhaust. The Wicker Man, however, is in a position even rarer and stranger than that. This movie made absolutely nobody rich. It lifted nobody to stardom, begat no wave (nor even trickle) of copycats, broke down no barriers to previously taboo subject matter. It was barely seen at all in its country of origin and fared little better overseas, thanks to a combination of cosmically shitty luck and distributors who were indifferent and uncomprehending at best, and downright hostile at worst. It’s difficult even to call The Wicker Man an influential movie. It sits, as it always sat, in a dusty, out-of-the-way corner of the occult horror subgenre that attained critical mass on screen with the release of Rosemary’s Baby in 1968, and what distinguishes it from the rest of the lot can’t easily be detached and repurposed for other projects. But just the same, the importance of The Wicker Man is not credibly open to dispute. More than just one of the strongest products of its era’s pagans-and-Satanists boom, The Wicker Man is also among the finest extant examples (well, mostly extant—nearly half an hour of director Robin Hardy’s original, preferred cut appears to be permanently lost thanks to one of the aforementioned hostile distributors) of a style that almost never works right on film. It’s a horror movie that holds back the scares— not for fear of offending sensibilities, or out of some misguided intellectual commitment to the supposed terror of the unseen, but in order to marshal its resources for an Operation Overlord of disorientation and dread to be sprung on the audience at a time and place of its choosing.

Sergeant Howie (Incense for the Damned’s Edward Woodward) is a cop based in some Scottish maritime town, whose regular duties entail patrolling the surrounding sea and its islands in a short-range, single-seat flying boat. I put him well under 40, but Howie is the sort of person who was born a surly old man. He belongs to some very conservative church, in which he is an active lay minister, and he approves of very little. His God did him absolutely no favors by permitting him to be born into an age that would include 1973. Even Howie’s fellow constables think he’s an enormous putz, not least for being still a virgin at his age even despite having a long-term girlfriend whom he has every intention of marrying. One afternoon, when Howie returns from a patrol, he finds a letter waiting for him, bearing an address in the offshore farming community of Summerisle. Famous all over Britain for its apples, Summerisle is the domain of an eccentric nobleman; Lord Summerisle (who’ll be played by Christopher Lee when we meet him later on) owns all the land on the whole island, and he uses the wide latitude traditionally granted to men of his station to organize the community’s affairs according to his own liking. Neither apples nor the privileges of landed gentry are the subject of the letter on Howie’s desk, however. Rather, it concerns a young girl named Rowan Morrison (portrayed in the accompanying photograph by Geraldine Cowper), who has apparently been missing for a matter of months. The anonymous author doesn’t come right out and accuse Lord Summerisle or the other villagers of covering up a crime with regard to Rowan’s disappearance, but the tone of the letter hints unmistakably at suspicions of foul play. Summerisle is technically within Howie’s area of responsibility (although its owner’s prickly attitude toward outsiders is such that he’s never actually been there), and if the sergeant has any inkling that finding Rowan will be anything other than a routine bit of police work, he gives no indication of it.

There are many words with which I could describe Howie’s experiences on Summerisle, but “routine” would not be among them. Hell, they’re not even routine within the context of “driven outsider vs. conspiracy of silence” stories. For one thing, the conspirators here aren’t exactly silent. Indeed, they’re very forthcoming for the most part, except that their cooperation with Howie’s investigation always winds up being the farthest thing from helpful. Half of what Howie hears from the islanders is totally untrue, while the other half consists of truths that lead in contrary directions— and more than once, the lies themselves turn out to be true in ways that the liars telling them seemingly could not have intended. The old men who greet Howie at the wharf where he lands claim never to have heard of Rowan Morrison, but they point the sergeant toward a woman who simply must be her mother. May Morrison (Irene Sunters) has a daughter, alright, but her name is Myrtle (Jennifer Martin), and she’s no more missing than Howie is. Myrtle, however, does admit to knowing Rowan— except that she’s apparently talking about her favorite among the island’s wild hares. Miss Rose the schoolteacher (Stop Me Before I Kill’s Diane Cilento) and her pupils alike assure Howie that there is no such child as Rowan Morrison on Summerisle, but the empty desk in Rose’s classroom and a notation in her roster quickly force her to concede that there used to be. Sure enough, Rowan has a grave in the island’s cemetery, yet the archivist at the hall of records (Ingrid Pitt, from Transmutations and Sound of Horror) can produce no death certificate, even though the town doctor (John Sharp, of …And Now the Screaming Starts and Jabberwocky) professes to have filled one out giving the cause of death as burning. And when Howie eventually secures permission from Lord Summerisle to dig up Rowan’s grave, he finds the coffin occupied by— well, what do you know?— a dead hare.

Meanwhile, Howie is constantly being thrown off his game by his flusterment in the face of local customs. At the Green Man Inn, the other patrons feel no compunction over singing ribald songs about landlords’ daughters not merely in front of Alder MacGregor the landlord (Lindsay Kemp, of Savage Messiah and The Vampire Lovers), but in front of his post-adolescent daughter, Willow (Britt Ekland, from Percy and Satan’s Mistress), as well. Miss Rose forthrightly teaches her students about the sexual symbolism of the Maypole (Howie has arrived just in time for the run-up to Summerisle’s May Day festival), and the folk song locally associated with the Maypole dance is similarly frank (to say nothing of how its description of the cycle of life, death, and renewal seems to verge on reincarnation). Lord Summerisle himself brings pubescent boys to Willow for instruction in sexual technique, apparently as a rite of passage. And on his way to ask the lord’s permission to exhume Rowan, Howie witnesses Miss Rose conducting a group of teenaged girls in frolicking naked around a bonfire in the center of an ancient megalith circle.

The explanation for all that comes partly from Miss Rose, and partly from Lord Summerisle, but all of it comes as a profound shock to Sergeant Howie. Summerisle has abandoned Christianity, lock, stock, and barrel, and embraced a reconstruction of the ancient Celts’ pagan faith. As His Lordship puts it to Howie, Jesus had his chance around here, and he blew it. What Lord Summerisle means is that when his agronomist grandfather bought the island in the late 19th century to serve as a laboratory for his botanical theories, he found the local people oppressed and afflicted by many things. Poverty, agricultural mismanagement, and economic injustice were prominent among the islanders’ woes, to be sure, but Grandpappy Summerisle was most strongly impressed by the life-abnegating strain of Protestantism that in his view encouraged people to accept their miserable lot in exchange for the hope of something better in the next world, rather that to strive for the betterment of this one. The original Lord Summerisle was a utopian at heart, and he wanted his island to shine with promise for the future, not just in the output of its fields and orchards, but in all things. So being also a nobleman who could get away with virtually anything on his own property, he converted his subjects as might an ancient king— taught them to love this life, to cherish its pleasures, and to venerate the natural world of which it was a part via the worship of long-forgotten gods. And at the same time, he taught them new ways to tend and manage their crops, bound up with the tenets of the new-old religion in such a way that the two would become mutually reinforcing, and act as a substrate for a new and altogether more functional culture. Howie may bluster and fume at this tale of organized apostasy, but looking around Summerisle today, it’s hard to argue that the return to paganism has done the island or its people anything but good.

Or at any rate, it seems hard to argue at first glance. Howie, driven by both his professional obligations and his philosophical commitments, has reason to look a great deal closer, however. The key fact, as it happens, is something that Howie has barely thought about since first observing it: the food at the Green Man is very bad, all canned, frozen, or otherwise processed and packaged. This in a farming community, at the height of spring. What’s more, Willow can’t even offer Howie an apple for dessert, apologizing that they’ve all been shipped off for distribution on the mainland. Apples are Summerisle’s cash crop, of course, but surely it’s customary to hold some of them back for the islanders’ own enjoyment? The answer to this seemingly minor puzzle is that last summer’s harvest was the worst in many years, and there’s nothing minor about that at all. Now what do pagan cultures traditionally do when catastrophe strikes? Yes, they try to buy off the gods with sacrifices, and the worse the catastrophe, the bigger and more vital the sacrifice. And at least as pagan religion is presented in pop culture, isn’t the highest form of sacrifice the ritual slaughter of a virgin girl? Suddenly, Howie understands everything. Rowan Morrison does indeed exist, and she isn’t dead after all. She’s being kept somewhere in preparation for her sacrifice at the May Day festival! Naturally, Howie’s first instinct is to rush back to the mainland and return with about a thousand more cops, but somebody sabotaged his plane while he was busy chasing around the island after traces of the missing girl. Besides, it’s April 30th already by the time Howie puts it all together; certainly too late to call for backup. Can one cranky Christian cop deprive an island of desperate pagans of the sacrifice their gods demand, all by his lonesome? Howie is about to find out…

It’s a rare horror movie indeed that not only can get away with doing nothing even ostensibly horrifying for the whole first hour, but is in fact stronger for that forbearance. The secret to The Wicker Man’s success here lies in its devoting that hour to other things at least equally interesting: a compelling mystery and a steadily intensifying clash of ideologies. Howie comes to Summerisle in crime-solving mode, and The Wicker Man follows the structure of the detective story for most of its length. However, it puts the viewer off balance practically from the start by diverting Howie’s efforts immediately from cracking the case into figuring out whether there’s really a case to be cracked at all. That is, on top of the usual mystery-movie business of scouring the action and dialogue for answers, we’re faced with the relatively novel predicament of uncertainty over the true nature of the questions. Any well-written mystery deepens before it gets resolved, of course, but The Wicker Man takes the technique to commendable, engrossing extremes. The real action, however, is on the philosophical front, as Howie’s search for Rowan Morrison exposes ever more starkly the way things are done on Summerisle, and that remains true even after The Wicker Man starts laying on the scares. What begin as disorienting bits of local color are gradually revealed as the motivating force of the plot, shifting the focus almost imperceptibly from mystery to horror. Even when the transformation is complete, however, this is not at all a film on the Rosemary’s Baby-Exorcist-Omen model that continues to dominate the occult subgenre even today.

There are three major points of divergence from that tradition, the most obvious of which is that the Summerisle cult is neo-pagan, not Satanic. In a more superficial movie, that wouldn’t matter much, and there’s never been any shortage of filmmakers unable to tell the difference. But it matters here because Satanists, like it or not, must operate within the framework of Christian cosmology. They may oppose the Christian God and all he stands for, but they inescapably do so on his own terms. A Satanist can never credibly dismiss Christ or Yahweh as having had his chance and blown it, for the very act of opposing something concedes that the thing being opposed has both power and relevance. Pagans, on the other hand, needn’t waste their time denying Christ or dethroning his Father; theirs are positive beliefs, in contrast to Satanism’s mere negation of Christianity. Summerisle’s sun god, sea god, and field goddess are not defined by their relationship to the God Howie recognizes, nor does their existence presuppose His.

The Wicker Man also differs from the mainstream of occult horror in that the threat it poses to its protagonists is not supernatural in origin. The gods of Summerisle never put in an appearance, and for the purposes of this story, it makes no difference whatsoever whether or not they even exist. The islanders believe in the beings they worship, and behave in full accordance with that belief. Holding that the success of this year’s harvest depends upon regaining the gods’ goodwill, they will not be stopped from carrying out the human sacrifice they deem necessary to achieve that end, but at all times it is the cultists, and not their gods, that Howie has to worry about. The Wicker Man thereby establishes its kinship with two of the best occult horror movies from before the post-1968 boom, The Seventh Victim and Eye of the Devil. Indeed, the latter film could almost function as a sequel to this one, hinging as it does upon the principle that when all else fails, only the sacrifice of the community leader himself will suffice. As Howie pointedly reminds Lord Summerisle during the climax, that’s an article of his people’s faith, too.

Which leads me at last to the most unusual thing about The Wicker Man, and the thing that makes it such a treasure: it is genuinely possible to articulate, at least in outline, what the faith of the Summerisle cult is, so that the collision between it and Howie’s conservative Protestantism can be examined in detail and treated as a fair fight, intellectually speaking. As a non-Christian— indeed, an anti-Christian— myself, I obviously bring a certain bias to this aspect of the film. Nevertheless, I don’t think it’s necessary to share my moral and theological perspectives to see the appeal in the Summerisle lifestyle, or to understand what the islanders get out of it. Ultimately, these are happy people. They do not live their lives hemmed in by taboos, beaten down by shame and guilt, or hobbled by fear of being punished for not living up to a by-definition impossible set of behavioral standards. The island’s social structure seems remarkably egalitarian, with men and women enjoying essentially the same levels of freedom and agency, and even Lord Summerisle carries himself more as first among equals than as seigneur among subjects. (How many wealthy noblemen do you think are in the habit of entertaining schoolteachers up at the manor-house?) There’s no visible reason (apart, obviously, from that mysterious, anonymous letter) not to take Lord Summerisle at his word when he assures Howie that the community is well ordered and largely untroubled by serious crime, which tends also to imply that the proceeds of the island’s agriculture are distributed equitably enough despite the medieval land-tenure arrangements. Summerisle, in other words, looks very much like the utopia its founder sought to create— except for that pesky business about the occasional need for human sacrifice.

Meanwhile, Howie makes a very poor pitch man for Christianity. As a practical matter, his religion appears to consist of little more than a very long and dispiriting list of prohibitions. And yet it is no less evident what benefit Howie derives from adhering to it. He is, after all, a cop, and Christianity as he practices it is nothing if not a faith for cops. Howie’s religion (and its privileged position in British society) essentially gives him license to tell whomever he disagrees with that they’re doing it wrong, and to threaten them, implicitly or explicitly, with official coercion unless they change their ways. It’s a hectoring, bullying, exultant exercise in moral masturbation, yet it nevertheless has one undeniable point of superiority over the beliefs of the islanders. It got the only human sacrifice that it will ever require out of the way 2000 years ago. And of course even Howie’s thuggish brand of Christianity must at least pay lip-service to its founder’s radical notion that meekness is the highest form of strength, humbleness the highest form of authority, forgiveness the highest form of justice— and to the gospel-writers’ corollary that a principled defeat is the highest form of victory. That last part is hugely important, because it turns The Wicker Man’s 70’s downer ending into something a great deal more complicated. Within Howie’s and the islanders’ respective conceptual frames, each can legitimately claim to have “won” the encounter. Each party to the clash performs exactly according to their deity’s expectations when the chips are down.

Of course it isn’t just Christianity and paganism coming to blows here. In a significant sense, The Wicker Man is also one of the most thoughtful cinematic examinations of the cultural and generational strife that was tearing most Western societies to pieces from within in the early 70’s. It doesn’t take a lot of imagination to see the people of Summerisle as a stand-in for the hippy counterculture. An insular group with highly idiosyncratic religious, political, and economic beliefs, who have cut themselves off from their parent society to pursue an agrarian lifestyle emphasizing harmony with nature and sexual liberty, and who seem to spend the bulk of their leisure time singing folk songs— Summerisle isn’t a hippy commune in the strict sense, but the Haight-Ashbury types would for damn sure be comfortable there. And as for Howie, he doesn’t need to stand in for the establishment; he is the establishment. What’s both curious and commendable about The Wicker Man when looked at from this direction is that it does not recognizably take sides. I mean, sure— the islanders practice human sacrifice, and they’re nominally the villains here. To that extent, they and the real-world dissidents they can be taken to symbolize are being demonized and condemned. But at the same time, the filmmakers clearly display a certain sympathy for the cult’s beliefs, and if you look closely at the thinking behind whom Lord Summerisle selected to be the sacrificial victim and how, the seigneur himself starts looking downright admirable, in a cockeyed sort of way. It isn’t just that he’s trying to secure the future wellbeing of his people; Lord Summerisle also seeks to do so in the way that will cause the least pain within his community. Even more than he had to begin with due to his approachability and egalitarianism, he thereby exemplifies a benign, compassionate, accountable form of authority that contrasts most favorably with Howie’s.

The Wicker Man’s exceedingly troubled release history (which began with the bankruptcy of the venerable British Lion studio, continued through several attempts by various successor companies to exploit the movie as a tax write-off, and concluded with the loss of all the original film elements— the latter rumored to have wound up as landfill beneath the highway when the M3 was extended past British Lion’s old Shepperton studio complex!), and the dismissive attitudes of nearly everybody who ever formally owned the picture, are very instructive. They hint, I believe, at an aspect of British horror cinema’s decline that goes unmentioned in the conventional story of competition from expensive Hollywood imports on one side and inability to grow beyond what worked from the late 1950’s through the mid-1960’s on the other. Here, after all, is a British horror movie as effective, as imaginative, as provocative as anything being made in America (or in Continental Europe, for that matter) in 1973. The Wicker Man’s existence is proof that Brit-horror could adapt and evolve— that it could not only embrace the subversiveness that was coming to define the genre as a whole in the 1970’s, but also develop it into something much more distinctive and intellectually stimulating than the crude nihilism into which contemporary American and Continental fright films were so often happy to descend. And its standing today as a secret classic suggests that it could have been a significant success, had its owners ever allowed it to be. The Wicker Man’s most formidable enemy was not The Exorcist, but a succession of studio heads who wanted only to bury it (and who literally succeeded in the end, if we believe the M3 legend). British Lion had been one of the UK’s biggest studios, and one of its buyers was the diversified capitalist juggernaut EMI; if British horror films were endangered in the 70’s by big-budget Hollywood imports, then surely The Wicker Man represented a wasted opportunity to hit back.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact