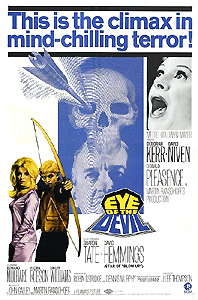

Eye of the Devil/13 (1967) ***½

Eye of the Devil/13 (1967) ***½

Lots of American studios formed partnerships with their British counterparts after the mid-1940’s. Hammer had deals first with Warner Brothers, then with Universal, and American International collaborated with just about every bottom-feeding production house in the Isles at one point or another, while often sending its own producers to England to make movies using local talent. MGM’s British venture, however, was of an altogether more serious nature— that studio went so far as to spin off an entire British-based subsidiary. When it comes to genre movies (horror, sci-fi, fantasy, and the like), the contrast between MGM-America and MGM-UK is both stark and fascinating. While the parent company was sinking so much effort into flashy and relatively expensive mediocrities like The Time Machine, Twice-Told Tales, and 7 Faces of Dr. Lao, the British division was taking a more low-key approach, cranking out some of the finest horror and science fiction of the 1960’s. In their way, these were audacious pictures. Shot on economical black-and-white film, without a lot of action and featuring little or nothing in the way of special effects, they appeared at a time when Hammer and Amicus were steadily raising the standards for onscreen sex and violence, while even tiny companies like Planet were beginning to shoot their horror flicks in lurid Pathecolor. The perennial favorites among the British-produced MGM horrors of this period are Village of the Damned, Children of the Damned, and (depending on how rigid your definitions are) the Robert Wise version of The Haunting. But there were other, lesser-known examples of the form, and one of these, Eye of the Devil/13, is nearly as good as its more famous sisters.

The first half of the film is calculated to keep you as close to completely mystified as possible. A bearded, aging man of distinctly rustic appearance gets off of the train in what I take to be Paris, and catches a cab for the ride out to the mansion of Philippe, the Marquis de Montfauçon (Old Dracula’s David Niven). The marquis is hosting a typically snooty high-society party at the time, but the man from the countryside doesn’t let that intimidate him. Evidently, Philippe knows who he is, too, because the visitor needs only to state that “It’s time” for the marquis to grasp what is expected of him. Later that night, when his wife, Catherine (Deborah Kerr, of The Innocents), goes looking for him to figure out when he’s coming to bed, she finds the marquis brooding in his darkened office. Philippe tells Catherine that the vineyards are failing back at the village of Belenac, the ancestral home of the Montfauçon family, and that he must go see what, if anything, can be done to save them. And mysteriously enough, although Philippe does not know how long he might have to be gone, he insists that Catherine and their children, Jacques (Rasputin, the Mad Monk’s Robert Duncan) and Antoinette (Suky Appleby), not accompany him. Catherine doesn’t really know why, but she doesn’t like the idea.

The reception Philippe receives at Montfauçon Castle suggests that Catherine is right to be worried about her husband. His Aunt Estelle (Flora Robson, from The Shuttered Room and The Beast in the Cellar) refuses to see him at first, and Father Dominic (Donald Pleasence, of Fantastic Voyage and The Hands of Orlac), the village priest, makes veiled reference to some arduous duty which he says he knew Philippe would not shirk when the time came. Meanwhile, back in Paris, Jacques has a curious sleepwalking episode in which he comes to Catherine for his toy motorcar— “so that I can go see papa.” It doesn’t sound like much, but Catherine has an intuitive sort of mind, and she takes the incident as reinforcement of her hunch that Philippe would be much better off if she were with him. Her own arrival in Belenac raises a tough question, however— if Catherine is in town to protect Philippe, then who’s going to protect her? At the top of the list of things Catherine might need to be protected from are a brother-and-sister pair (who look alarmingly like the children of Midwich all grown up) called Christian and Odile de Caray (David Hemmings, from Deep Red and Barbarella, and the ill-fated Sharon Tate, of The Fearless Vampire Killers and Rosemary’s Baby). Neither speaks much, Christian has an unnerving habit of shooting birds and things with his bow under circumstances in which he could easily hit innocent bystanders, and Odile possesses hypnotic (and perhaps even sorcerous) powers. But the real confirmation that bad business is afoot in Belenac comes when Catherine spies the Caray siblings sneaking into the castle with a dove Christian had killed earlier, and follows them at a discreet distance straight to the scene of some kind of pagan ritual being conducted in the basement.

Catherine will have a lot more snooping to do before she gets a handle on the true threat hanging over her husband’s head, but once she has all the pieces together, the picture they form is grim indeed. The inhabitants of Belenac are indeed pagans, but of greater importance, so are Father Dominic and Philippe de Montfauçon. Their religion holds that the earth requires periodic sacrifices if it is to remain fertile, and that it is the responsibility of the village’s seigniorial family to provide those sacrifices in the form of the reigning marquis. The village priest presides over the ceremony at the head of a circle of twelve local notables, while the Caray family is in charge of the actual killing. For Catherine’s purposes, the most difficult aspect of the whole situation is that Philippe, as a practicing adherent of Belenac’s strange religion, might very well refuse to let himself be rescued...

What I kept thinking about as I watched Eye of the Devil was how great a double feature it would have made in conjunction with a later, and more famous, British movie about modern-day pagans: The Wicker Man. This movie might be just a bit upstaged by that one, as it has only Donald Pleasence to compete with Christopher Lee’s performance as The Wicker Man’s heathen priest, but it’s one of the very few other films I’ve seen that devotes anywhere near as much attention to the beliefs of its cultists. In sharp contrast to what you usually encounter in movies about pagan or Satanic cults, Eye of the Devil posits a faith that makes a considerable amount of real-world sense. Its gods are not evil— they’re just very, very demanding— and its doctrines have assimilated Christian notions in an extremely realistic manner. Most intriguing is the way in which it turns the Marquis de Montfauçon into a sort of surrogate Christ, requiring him to sacrifice himself for the good of his people; the ritual of sacrifice itself even goes so far as to surround the doomed lord with twelve apostle figures who stand by and bear witness to his act of ultimate generosity. It’s startling even today, and must have come as a real shock in 1967.

Beyond all that, Eye of the Devil is just an extremely well-made movie. Director J. Lee Thompson exploits the natural atmosphere of the castle in which most of it was filmed to great effect throughout, and generally displays an exceptional eye for frame composition. The only performance that’s anything less than spot-on is Suky Appleby’s as Antoinette, but who really expects decent acting from a seven-year-old anyway? Especially surprising is Sharon Tate, who actually gets to act for once, and who acquits herself admirably. Maybe she should have taken a hint from Barbara Steele, and concentrated on villainous roles. There’s just one thing wrong with Eye of the Devil, but unfortunately it’s kind of a biggie. The movie feels much longer than its 92 minutes. To be fair, this kind of Wilkie Collins-ish conspiracy mystery demands a deliberate pace if it’s going to function properly, but Eye of the Devil is a little too deliberate. Audiences with short attention spans will be climbing the walls within the first half hour, and even I found my concentration slipping in a couple of places. Even so, Eye of the Devil deserves to be far better known than it is, and any fans of MGM’s other British-produced 60’s horror films owe it to themselves to give it a look.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact