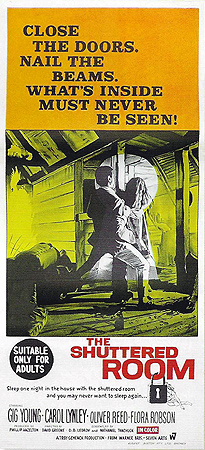

The Shuttered Room (1967/1968) **½

The Shuttered Room (1967/1968) **½

Here’s the thing: Most people don’t know when they’re going to die, so they keep making plans for things they’re going to do later right up until the moment when all planning is rendered permanently irrelevant. And since most people also lack the cursed blessing of a brain that can preserve all of its contents indefinitely, those plans usually leave paper trails for the survivors to find and sort through. Normally, a dead person’s to-do list is of no interest to anyone but friends and family, but when the deceased is a professional author, his or her documentary legacy is almost certain to contain traces of projects that never reached completion, or indeed were never properly begun. The greater an author’s standing and popularity, the stronger the pressure and/or temptation will be to do something with those unfinished, fragmentary, and embryonic works after their death, especially if there are other writers (or aspiring writers) among the heirs and executors. When Howard Phillips Lovecraft succumbed to intestinal cancer in March of 1937, the aunt with whom he’d been living put his papers in the hands of his friend and correspondent, Robert H. Barlow, whom Lovecraft had designated (perhaps merely informally, in conversation with his aunt) as his literary executor. Barlow was an odd choice, for he was just nineteen years old at the time, with little experience in the business of letters, and effective control of Lovecraft’s writings, both published and unpublished, quickly devolved upon August Derleth instead.

Derleth, too, was a longtime Lovecraft pen-pal, and a staunch partisan of his work— even if Derleth’s own writing in the same mode (which we’ll get to in a bit) suggests that he didn’t really understand what he was so ardently promoting. His first move in what would become a lifelong campaign to keep his departed friend in the public eye was to push Dorothy McIlwraith, who was brought aboard as assistant editor of Weird Tales in 1938, and who graduated to the big desk two years later, to accept some of the pieces (including the now highly regarded “The Shadow Over Innsmouth”) that Farnsworth Wright had rejected during his long and pivotal tenure as the magazine’s chief. Then, and of far more lasting significance, Derleth brought his own editing talents to bear, compiling the first-ever collection of Lovecraft’s fiction in book format. When none of the established publishing firms showed any interest, Derleth and Donald Wandrei launched one of their own to get the volume into print; ten years later, their Arkham House imprint was arguably the most prestigious and influential boutique publisher of fantastic fiction in the United States. Derleth also went into overdrive incorporating Lovecraft references into his own writing, gradually codifying his mentor’s vague and deliberately inconsistent fictional cosmology into a more or less coherent mythos. Finally— and it’s surely no coincidence that Robert Barlow was just as dead as Lovecraft by this point— Derleth did the nearest thing in his power to flat-out raising HPL from the dead, raiding his papers for fragments, plot outlines, and story notes, and completing those nascent works as “posthumous collaborations.” It is this final phase that most accounts for the love-hate sentiments that so many modern Lovecraft fans harbor toward August Derleth. On the one hand, Derleth’s decades of ever more inventive boosterism are almost certainly the only reason why Lovecraft was not forgotten every bit as utterly as Kirk W. Mashburn or G. G. Pendarves. But on the other, Derleth, whether deliberately or not, was twisting what he dubbed the “Cthulhu Mythos” into a form its creator would barely recognize, focused on a Manichean opposition between good Elder Gods and evil Great Old Ones that was sharply at odds with Lovecraft’s pure and radical dystheism. And furthermore, those “posthumous collaborations” sucked a whole lot— and not even in the intriguing and fiercely personal ways that Lovecraft’s genuine output frequently sucked. By appropriating his mentor’s name, Derleth was not only cloaking himself in largely unearned glory, but also devaluing that name by associating it with predictable, pedestrian stink-bombs like “The Horror from the Middle Span” and “The Shuttered Room.”

Yes, you were wondering what any of that had to do with shuttered rooms, weren’t you? “The Shuttered Room” was the headlining story in the first Arkham House book to feature Derleth’s team-ups from beyond the grave, and maybe more than any other such tale, it demonstrates the dreary folly of the entire enterprise. Simply put, it’s a limp sequel to both “The Dunwich Horror” and “The Shadow Over Innsmouth” which brings a collateral descendant of the former tale’s Whately clan back to the old homestead to face an “ancestral horror in the attic” situation rehashed from “The Lurking Fear,” with one of Innsmouth’s frog-like human-merman hybrids now residing in the locked room formerly occupied by the less human of the original Whately brothers. It bears an embarrassing resemblance to Maurice Sandoz’s gonzo gothic, The Maze, and fans who wish for some reason to see a faithful film version of “The Shuttered Room” would be much better served by the 1953 Allied Artists adaptation of that novel than by the official Shuttered Room movie shot in Britain for Warner Brothers/Seven Arts a decade and a half later. That isn’t because The Shuttered Room is a bad film, but rather because screenwriter D. B. Ledrov has excised all trace of the supernatural from the story, recasting it as pure backwoods horror of roughly the sort that would loom large over the fright-flick landscape in the wake of Deliverance and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre.

We begin with a little girl waking up screaming in the middle of the night, as seen through the eyes of whom- or whatever is responsible for her terror. The commotion wakes the girl’s parents, who race to the rescue— dad ranting as they go to the effect that mom must have forgotten to lock the door. Mom bursts in and scoops up the POV cam before it can do any harm, then hustles up to the attic, murmuring calming platitudes to her unseen burden all the while. The attic contains a room with a door that looks like it could stop Grond dead in its tracks, and it is therein that the woman confines the person or thing that was making her daughter flip her shit.

Given how the one character’s face dissolves into the other’s at the start of the opening credits, I think it’s safe to assume that the little girl grows up to be 21-year-old Susannah Kelton (Carol Lynley, of The Night Stalker and Beware! The Blob). Susanah was raised by foster parents in New York for most of the intervening years, and it wasn’t until a lawyer called to inform her of her parents’ deaths and her fairly substantial inheritance that she had any idea of her ties to the Whatelys of Dunwich Island, off the coast of Massachusetts. The inheritance in question is the old mill where she and her folks lived during her earliest childhood, a place she remembers only dimly but with considerable unease. Nevertheless, her old-enough-to-be-her-dad husband, Mike (Gig Young, from Game of Death and The Woman in White), is intrigued by the prospect of a second home out in the country, so now the Keltons are on their way up the coast to see what, if anything, might be done with the mill.

In the hierarchy of shitty vacation spots, I’d rank Dunwich somewhere between Amity Island at the height of shark season and Camp Crystal Lake. The island is a lawless little enclave of poverty, ignorance, and superstition, and the locals really don’t like outsiders— even outsiders who technically belong to Dunwich’s most prominent family. The Whately mill is universally regarded to be haunted or cursed or something, and when Mike talks to Zebulon Whately (Blood of the Vampire’s William Devlin), the relative whom the family lawyer said to seek out for directions and other assistance, the old man does his best to convince Mike to get back in his car, turn around, and forget all about doing anything with his wife’s property except to let it finish rotting into the ground. And then there’s Susannah’s cousin, Ethan (Oliver Reed, of The Devils and Burnt Offerings). Ethan leads a gang of country-boy hooligans who wouldn’t seem a bit out of place in I Spit on Your Grave, and he develops an incestuous letch for Susannah the instant he lays eyes on her. What’s more, there’s no realistic way for Susannah to avoid Ethan, for he happens to live with their Aunt Agatha (Flora Robson, from Eye of the Devil and The Beast in the Cellar), the one person whom the girl vividly recalls from her Dunwich days, and whom she had hoped to rely on to facilitate whatever reintegration into the local community might be possible. Agatha has a reputation as a sort of gray witch— a trusted herbal healer and wise woman, but not somebody it pays to cross or to disrespect— and although she is friendly enough when Ethan leads the Keltons to the lighthouse where he and Agatha live, Susannah’s aunt is just as adamant as Zebulon that nothing good can come of trying to rehabilitate the old mill. She doesn’t say as much, of course, but she clearly knows perfectly well that the locked room in the mill’s attic still has its troublesome tenant, and all the laws of horror movie plotting demand that that tenant be a great deal more troublesome now than sixteen years ago.

In point of fact, though, the thing in the attic is scarcely any trouble at all, and I truly can’t tell how much of my dissatisfaction with The Shuttered Room stems purely from unmet expectations. I’ve read the story, so I assumed there was going to be some manner of monster in the room upstairs, even if I also figured the filmmakers would have the good sense not to make it a man-sized frog. Meanwhile, any non-novice horror fan will recognize at once on the basis of the opening scene that the attic-lurker is really Susannah’s sibling. So when we’re formally introduced to the girl’s utterly feral and violently territorial twin sister in the climactic scene, and it turns out that she isn’t even horribly deformed, it seems like rather a waste of all that meticulously engineered buildup— especially since mad sister Sarah isn’t really the villain of the piece! Rather, she’s more of an atmospheric device that finally justifies its presence when’s she’s inadvertently turned loose against the baddies.

Those, naturally, would be Ethan and his gang, and while a mob of psychotic hillbillies is about the least Lovecraftian menace imaginable, I can’t get that pissed off at a movie that casts Oliver Reed as an unhinged sex predator. Basically, what we have here is a rural American version (or at any rate, a British conception of a rural American version) of Reed’s gang in These Are the Damned, with their adolescence even further suspended and a thick veneer of class resentment spread over them, and it truly is remarkable how much they resemble a trial run for I Spit on Your Grave’s backwater rapists. Unfortunately, The Shuttered Room remains unwilling to commit to them as the primary threat until the last few scenes, with the result that most of the film plays out with no clear sense of what’s at stake for Mike and Susannah. Red herrings are one thing, but a band of violent mooks rampaging around a town with no apparent law enforcement organization and an unseen whatsit skulking in the protagonists’ own attic are such obviously incommensurable things to hold over the characters’ heads that the filmmakers’ reluctance to choose between them creates a fundamental confusion as to what sort of movie this is even supposed to be. That indecisiveness is rendered doubly regrettable because director David Greene handles both the gang and the elements relating to the supposed Whately curse with a confidently individualistic approach to suspense that belies his background as a veteran of series television. The Shuttered Room never settles for that colorless professionalism that one quickly comes to expect from TV directors graduating to their first feature film, yet it is equally far removed from the stock techniques of British horror cinema that had evolved since the late 1950’s (and which had been adopted, with one degree of modification or another, by movie industries all over the Western world by 1967). In a strange way, the vibe of the film reminds me most of some of the more serious, bigger-budgeted blaxploitation movies from the following decade— a richly detailed panorama of dirt, despair, and life itself decaying into garbage before the eyes of people who are mostly too stunted and beaten down by poverty and social neglect to bother asking for anything meaningfully better. The difference, of course, is that here we’re dealing with rural blight, and the inhabitants of Dunwich are shown through the Keltons’ eyes as an inscrutable and basically hostile Other. It’s pretty powerful for half an hour or so, before it becomes apparent that Greene and Ledrov are all too perfectly content to kick back and do nothing much at all through the entire second act. The other big frustration concerns the characterization of the Keltons themselves. Mike Kelton is kind of a smug jackass, but that isn’t so bad in context. 30 years older than his wife, and representing a generation of men who took female weakness and incompetence for granted, Mike is at least a believable figure, even if it’s pretty hard to like him. Susannah is the bigger problem, for it’s almost as if she’s trying to live down to her husband’s expectations. Rarely have I seen a more contemptibly useless heroine, and the impression The Shuttered Room conveys that Susannah was meant to stand for the modern, liberated young women of the late 60’s makes her inability to take care of herself on any level even more galling. All in all, I’d like to give The Shuttered Room a heavily qualified recommendation, but it does so much to defy so many of the wrong expectations (along with a few of the right ones, it’s true) that I’m not at all sure who the viewer most likely to appreciate it would be.

The B-Masters are doing H.P. Lovecraft this month. Well, sort of in my case. But the rest of the gang chose much more defensibly than I did, as a click on the banner below will reveal:

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact