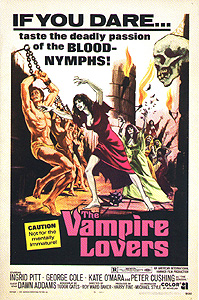

The Vampire Lovers (1970) ***

The Vampire Lovers (1970) ***

Scars of Dracula and The Horror of Frankenstein boded very ill for the future of Hammer Film Productions, but to audiences who went to see The Vampire Lovers instead, it probably was not remotely apparent that the 1970’s had caught Britain’s foremost makers of horror movies with their pants down. Whereas the former two films offered more of the same old shit— or worse, a “hip,” “ironic” take on the same old shit, devised by people who utterly failed to grasp the concepts of hipness and irony— The Vampire Lovers was something altogether new to the British screen. True, movies about female vampires had been hinting delicately in the direction of Le Fanu-esque lesbianism ever since Countess Maria Zaleska decided that there were better things to do with an artist’s model than to paint her picture (but not, you know, those better things) in Dracula’s Daughter. True also that Continental filmmakers had been blurring the line separating horror movies from sex movies for some considerable while by 1970, and that one of the earliest films to do so, Roger Vadim’s Blood and Roses, had in theory been based on Le Fanu’s “Carmilla.” But Blood and Roses did very little that would have been censorable in previous years, and its basis in “Carmilla” is, upon close examination, only slightly stronger than the purely imaginary one sometimes claimed for Vampyr; it actually functions more as a sequel to Le Fanu’s short story than as a direct adaptation of it. That gives The Vampire Lovers the distinction of being the first serious attempt to film “Carmilla” more or less as it was written, and among the first serious attempts to bring the sex-horror genre across the English Channel with all the blood and nudity intact. It was an odd fit for Hammer, but it was also one of the few films the studio made in the early 70’s that performed according to expectations, and Hammer’s only horror movie of the decade to launch a whole new franchise.

In 1794, the sister of Baron Joachim von Hartog (Douglas Wilmer, from The Golden Voyage of Sinbad and The Brides of Fu Manchu) was killed by a vampire (Kristen Lindholm, of Crescendo and The Love Factor). Not just any vampire, either; the assassin was a member of the terrible Karnstein clan. This bloodsucker fucked with the wrong family, though, for the baron was well versed in the lore of the undead. Joachim tracked his sister’s killer to her tomb in the graveyard at the ruins of Castle Karnstein, and forced a confrontation by stealing the monster’s burial shroud. (In this film, a vampire is unable to sleep except wrapped in the shroud in which it was originally buried.) Baron von Hartog was stymied at first by the vampire girl’s almost literally hypnotic beauty, but regained his composure the instant she bared her fangs for the attack. One sweep of Joachim’s saber later, his sister was avenged. Then, just to be sure, the baron spent the rest of the night digging up the whole cemetery, and driving stakes through the hearts of any un-decayed bodies he found within the graves.

There are other Karnsteins, however, no less deadly than those Baron von Hartog dispatched. In the Austrian duchy of Styria, General von Spielsdorf (Peter Cushing) is about to receive a visit from some of them. The reigning countess of the infernal lineage (Dawn Addams, from The Vault of Horror and Riders to the Stars) arrives late to a ball at the general’s chateau, in company with a stunning girl whom she introduces as her daughter, Marcilla (Ingrid Pitt, of The House that Dripped Blood and The Wicker Man). Marcilla is a huge hit with the general’s male guests— all but Carl Eberhardt (Jon Finch, from Frenzy and Lurking Fear), the manager of von Spielsdorf’s estate. He has eyes only for the general’s niece, Laura (Lust for a Vampire’s Pippa Steele). In fact, Marcilla seems rather taken with Laura herself— at least, she spends a lot more time looking across the room at her than at any of the men she takes up on their invitations to dance. Suddenly, a tall, pale man in a scarlet-lined black cloak (John Forbes-Robertson, from Lifeforce and The Legend of the 7 Golden Vampires) hurries in with an urgent message for Countess Karnstein; evidently one of her relatives has just died, and her presence on the scene is required as soon as possible. The journey there will be long and arduous, though, and the countess fears the strain it will put on her daughter’s delicate constitution. Fortunately for her, von Spielsdorf is a true gentleman. He offers to let Marcilla stay with him and Laura until such time as the countess is able to return and collect her.

What’s fortunate for Countess Karnstein and Marcilla is most unfortunate for the von Spielsdorfs, however. The entire business has been but a ruse to install one of the Karnstein vampires in a home where no one knows their true natures. Laura and Marcilla become fast friends— so fast, in fact, that their friendship seems to allow no room for anyone else. The general doesn’t think it’s healthy, and Carl doesn’t like being shut out just when it looked like he might be gaining ground in Laura’s affections. And of course it isn’t healthy at all. Laura begins suffering from recurring nightmares in which she is smothered in her bed by a gigantic cat— dreams that coincide with the solitary walks around the castle grounds which Marcilla claims to take each night to explain her absence from her own bedroom. Soon Laura starts visibly wasting away, and although the local doctor (Ferdy Mayne, of Frightmare and Conan the Destroyer) sees nothing wrong with her that a heavier, more iron-rich diet wouldn’t fix, von Spielsdorf fears the worst. Inevitably, the general is quite right, and Laura dies in her sleep not too much later. Marcilla vanishes mysteriously at just the same time, and both doctor and general are left entertaining thoughts about the strange lesions on the dead girl’s neck that they would each have rejected out of hand even 24 hours ago.

Among von Spielsdorf’s friends is an Englishman named Roger Morton (George Cole, from Fright and Mary Reilly), who has recently moved to Styria with his daughter, Emma (Madeleine Smith, from Taste the Blood of Dracula and Theater of Blood); his estate manager, Renton (Harvey Hall, of Gorgo and The Sex Thief); and a French governess by the name of Perrodot (Kate O’Mara, from The Horror of Frankenstein and Corruption). Shortly after the tragedy in the general’s household, a carriage wipes out on Morton’s property while taking too tight a turn at too high a speed. And what do you know? The driver of the carriage is the pasty-faced messenger who once interrupted von Spielsdorf’s ball, and the passengers are Countess Karnstein and Marcilla— only this time the girl is calling herself “Carmilla,” and the countess is claiming her as a niece instead of a daughter. Again there’s a sob story about an unforgiving schedule and a death in the family, and the next thing Morton knows, Emma is insisting that Carmilla stay with them while Countess Karnstein sets her affairs in order. Nor is that the only parallel with events at Castle Spielsdorf. Emma, too, forms a more than ordinarily friendly bond with the vampire, and begins complaining of both nightmares about cats and weakness and lethargy during the hours of daylight. Morton gets called away on business, however, so unlike the general, he doesn’t directly see what’s happening to his daughter. Emma has only Renton and Mademoiselle Perrodot to look out for her, and Carmilla’s seductive charms work as well on those two as they do on her primary target.

That said, neither one of Emma’s guardians succumbs at once, and Renton lasts long enough to seek medical assistance for the ailing girl. This is the same doctor who attended Laura, and her symptoms naturally strike him as familiar. The doctor sends for Morton and von Spielsdorf, upon which the general— who has been doing his homework and then some since Laura’s death— sends Carl to stand guard over Emma, and sets off himself in search of a man he’s read about who might be able to help in a more decisive manner. Yeah, he’s talking about Baron von Hartog. It’s been 20 years or more, to judge from the whiteness of the baron’s hair, but once a vampire slayer, always a vampire slayer. Von Hartog identifies this Marcilla-Carmilla pest as Mircalla Karnstein, a member of the family who died over two and a half centuries ago, in 1546. Her portrait was on display in Castle Karnstein on the night of the baron’s fraternal revenge, but he was unable to locate her grave during his frenzy of digging and staking. He nevertheless believes that Mircalla’s tomb is around there somewhere, and that if he and his new allies can find it, they will be in a position to save Emma. She clearly hasn’t long to live, though, so Morton and the two lords will have to embark on their coffin-hunt immediately— which inescapably means that Carl will be on his own against the vampire and her two enthralled accomplices at the Morton place in the meantime.

“Carmilla” is a little on the long side, and is structured more like a novel than typical short story. It is thus almost perfectly suited for adaptation to feature film— short enough for the whole tale to fit comfortably within an hour and a half, but not so short as to require the invention of great swaths of new material to fill out the running time. Screenwriter Tudor Gates did indeed stick remarkably close to the source, too. His main alterations were to merge two characters into Baron von Hartog, giving the latter a more streamlined version of his predecessors’ composite background, and to move both von Hartog’s story and General von Spielsdorf’s into their strict chronological places within the narrative. J. Sheridan Le Fanu held both in reserve for use as revealing flashbacks, which rendered the final chapters of “Carmilla” somewhat ungainly. Gates’s approach also entails some clumsiness, however, with its weird double prologue and its attendant postponement of the main action’s inception until what would normally be the beginning of the second act, and even then the film version doesn’t completely dispense with third-act flashbacks. The awkwardness is most obvious with the von Hartog stuff. As the central figure of the opening sequence, he clearly has to be important somehow, but the movie is three quarters over before anyone so much as mentions his name again. The repositioning of the von Spielsdorf material is more successful. Not only does it spare us a long and intrusive digression right on the verge of the climax (see Larry Buchanan’s “It’s Alive!” for an illustration of how well those usually work), but it also casts a pall of bleak inevitability over the Mortons’ turn in the spotlight. We know what’s coming, and as we watch Emma slowly lose herself to Carmilla, we’ll simultaneously be thinking about how many times over the last two centuries Mircalla and her elders must have pulled this same deadly con on other noble families across the Habsburg Empire. Few other movies have so adroitly evoked the continuity of a vampire’s immortal reign of terror, and I’m willing to tolerate a few graceless lurches and unsightly plot sutures in exchange.

Another respect in which The Vampire Lovers is surprisingly adroit is its most un-British melding of sex and horror. Making a film both effectively sexy and effectively horrible by the rapidly rising standards of the 1970’s was a particularly tall order for Hammer, steeped as that studio was in the paternalistic moralism of the late 50’s and early 60’s. And indeed The Vampire Lovers is ultimately just as paternalistic and moralistic as anything the firm produced during the earlier era, nudity and lesbianism notwithstanding. But in much the same way as The Kiss of the Vampire seven years before, that combination of reactionary outlook and libertine presentation creates an internal tension that works strongly to The Vampire Lovers’ advantage. The heroes of both films are stolid, upright father figures, guarding what they conceptualize as the virtue of the young women under their care against an incursion of wanton, ungodly sexuality, which is shown to be alluring and repellant at the same time. To understand why that framing works so well in both The Kiss of the Vampire and The Vampire Lovers, it is instructive to look at a third Hammer production in which it doesn’t work at all, The Devil Rides Out. In 1963, Dr. Ravna’s undead swingers’ club was at the far reaches of cultural acceptability, however demure the handling of it dictated by the British Board of Film Censors, and the whole length of The Kiss of the Vampire feels suffused with the sense that its creators were getting away with murder. By contrast, The Devil Rides Out, with its Mormon Temple picnic of a devil orgy, looks hilariously square in the context of 1968. Mocata’s cult is neither alluring nor repellant— it is merely silly, and the Duc de Richelieu looks even sillier for being so worked up over it. In The Vampire Lovers, finally, Hammer were once again pushing the limits in a significant way, and once again the result is a film that seems to be shocked at its own immorality. That sort of cognitive dissonance is perfect for a vampire movie, or at least for any vampire movie in the tradition of John Polidori’s “The Vampyre,” where the monster personifies the seductive power of evil.

However, for all its effectiveness and promise, there was one ominous fact about The Vampire Lovers, a hidden harbinger of the same doom foretold by the lesser films I mentioned back at the beginning of this review. Unlike previous Hammer hits, this was not an in-house undertaking. I don’t mean just the financing kicked in by American International Pictures, either. Hammer Film Productions had nearly always made skillful strategic use of foreign funding, so the alliance with AIP was new only in the sense that Hammer had never partnered with that particular firm before. The studio’s usual overseas backers— Universal, Columbia, Warner Brothers-Seven Arts— could hardly have been expected to embrace such a project, whereas AIP had no good name to sully. No, the disquieting innovation here was that the idea itself behind The Vampire Lovers originated outside the company. Tudor Gates and producers Harry Fine and Michael Style were in business together for themselves; having arrived at the conclusion that a forthright “Carmilla” movie would sell tickets, they simply pitched the idea to the studio they figured could make the most use of it. So if The Vampire Lovers feels less like Hammer than some lurid indie of the Peter Walker-Norman J. Warren persuasion, it’s because at bottom it basically is one. What we see here, then, is yet another strategy that Hammer could have pursued into the 70’s, coopting the creative energy of independent operators, and either inviting them aboard once a solid working relationship had developed, or having them in effect retrain the Hammer old guard for the new era. In fact, however, the studo did no such thing, or at least not with the sort of commitment that might have saved them. But to return once more to the vantage point of 1970, an outside observer might well have surmised that just such a program was in the offing. After all, the Gates-Fine-Style team was back at work almost instantly with a follow-up to The Vampire Lovers, while yet a third Carmilla movie took shape in the background. Those are other stories, though, which we’ll deal with in their appropriate places.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact