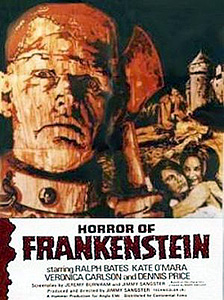

The Horror of Frankenstein (1970) *½

The Horror of Frankenstein (1970) *½

One of Hammer Film Productions’ problems going into the 1970’s was that the studio was still almost completely dependent on the same stable of actors that had assisted their rise to prominence in the late 1950’s. Not that there was anything wrong with Peter Cushing, Christopher Lee, Thorley Walters, or the rest of that lot (save perhaps a few extra gray hairs here and there); the point was that Hammer had not done nearly as much as they should have to nurture new talent through the intervening decade. Even when star-caliber performers like Andrew Keir and Clifford Evans had fallen into Hammer’s orbit, no one had properly appreciated their potential usefulness, and they were permitted to vanish after making just one or two films for the company. Meanwhile, neither Anthony Hinds nor the two Carrerases seemed capable of recognizing any actress except Barbara Shelley as more than a delivery system for a nice pair of tits. However, the most glaring inadequacy of Hammer’s approach to casting during the 60’s was their persistent failure to attract and retain interesting young men. Consider the amazing parade of drips and losers who played the supposed romantic leads in the studio’s mature gothics. Then think about the exceptions to the rule— Sandor Eles in The Evil of Frankenstein, Ray Barrett in The Reptile, Robert Morris in Frankenstein Created Woman— and ask yourself why they didn’t become the nucleus of a steady company B-team, suitable for promotion to headliner status as the need arose.

To be fair, Hammer’s leadership understood that this situation was untenable, and they put a lot of effort into the search for a new star once the 70’s were upon them. Unfortunately, in their cluelessness about the youth whose pocket money they coveted, they seemed to think that any fresh-faced lad with sufficiently long and floppy hair would do the trick. Among the defining features of Hammer’s final decline was thus a succession of sad campaigns to convince audiences that this or that charisma-vacuum pretty boy was the next Christopher Lee. And once again, promising performers (think Mike Raven, Robert Tayman, Damian Thomas, etc.) remained mere blips on the radar screen, left to get most of their work from feisty but impoverished independent producers instead. In 1970 specifically, James Carreras was pushing a handsome 30-year-old by the name of Ralph Bates. Bates had done a lot of stage and television work, and it’s possible that he truly excelled in those environments. On the basis of the movies he made for Hammer, however, Carreras’s enthusiasm for him appears totally inexplicable. Initially, the plan was for Bates to assume the mantle of Dracula from the increasingly difficult and cantankerous Lee, who was forever telling journalists that he was through with the part anyway. Hammer’s overseas distributors were having none of that, though, and the promise of continued American box office receipts would carry the unhappy marriage between Lee and the Dracula franchise through five more years and four more movies. Instead, Bates briefly became the ersatz Peter Cushing, not only taking over for him when he bowed out of Lust for a Vampire, but even inheriting the role that had made Cushing famous to begin with. Having been forbidden to reboot the Dracula series, Carreras sent his other flagship franchise back to the beginning in its place, under the ominously generic title, The Horror of Frankenstein.

Victor Frankenstein (Bates, also in Taste the Blood of Dracula and Dr. Jekyll & Sister Hyde) is an extremely talented student, who is nevertheless the least favorite pupil of all his teachers. He sasses back in the classroom, feels free to ignore any lecture that doesn’t instantly seize his interest, and tomcats around with seemingly every girl in school. Naturally the other kids all adore him, especially Elizabeth Heiss (Veronica Carlson, from Old Dracula and Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed). You know how it is with these teenagers today, right? Mind you, Victor is at the very least a second-generation randy goat, for his father the baron (George Belbin, of Games that Lovers Play and Disciple of Death) has hardly been a lonely sort since the death of his wife an unspecified number of years ago. In fact, Baron Frankenstein has actually managed to out-compete his son for the favors of their adolescent chambermaid, Alys (Kate O’Mara, from Corruption and The Vampire Lovers). Alys isn’t the main point of contention between Victor and the baron, however. Despite the impression you might form from his on-campus conduct, Victor is extremely serious about his studies. In fact, he hopes to go to Vienna next year and enroll in the university’s medical program. Believe it or not, though, his father won’t hear of that. In his own words, “You’ll see me in my grave before I let you gallivant off to Vienna for a couple of years!” Victor takes that as his cue to engineer a hunting accident for his dad, rigging one of the old man’s fowling guns to explode in his face when fired. Look out, Vienna— here Victor comes!

As it happens, the young baron attends university almost exactly long enough to befriend fellow med-student Wilhelm Kassner (Graham James, of Blood from the Mummy’s Tomb) and to impregnate the dean’s daughter. Whoops. Frankenstein decides to slip away home before he winds up married against his will, and on his way out the door, he persuades Kassner to accompany him. Think of it— a whole castle all to themselves, and nobody to meddle in their scientific investigations! Kassner is a little horrified to learn that none of the literal tons of lab equipment that his host bought recently has been so much as taken out of the shipping crates, and he seems fundamentally unclear as to what these experiments of his and Frankenstein’s are supposed to be, but he doesn’t intend to let either of those things spoil his enjoyment of a summer spent boarding at a real baronial estate.

The next two or three reels are mainly devoted to reintroducing Frankenstein’s old associates, and to catching Victor up on what they’ve been doing since graduation. Alys is still at the castle taking care of the place, and despite her disparaging attitude before, she’s just as ready to keep her new master’s bed warm for him as she was the old baron’s. Henry Becker (Jon Finch, from The Last Days of Man on Earth and Frenzy) is a police lieutenant now, while Victor’s sometime admirer, Maggie (Thirst’s Glenys O’Brien), has moved on to become Henry’s wife. And poor, stupid Stephan (The Final Conflict’s Stephen Turner), who made it through school only because Victor did all his homework for him, has surprised absolutely nobody by turning into the village odd-job man— although the proficiency Stephan displays in the kitchen when Alys hires him on as the baronial chef is perhaps less to be expected. As for Elizabeth, she’s still carrying the torch for Victor, as he discovers when he and Wilhelm find themselves fortuitously in a position to rescue her and her father (Bernard Archard, from Krull and Corridors of Blood) from a band of highwaymen. The baron’s subsequent, surreptitious theft of one dead bandit’s head is nearly the only indication offered thus far that anyone involved in making The Horror of Frankenstein remembers what we’re really here to see.

Things begin turning more properly Frankensteinian when Victor similarly steals Elizabeth’s dad’s pet turtle, Gustav. This he does so that he and Wilhelm can first kill it, and then bring it back to life. Once that experiment succeeds, Frankenstein informs Kassner of his true objective, to create and animate a man using salvaged bits of dead bodies. To that end, Victor makes a long-term deal with a body snatcher (Dennis Price, from Horror Hospital and Theater of Blood) who likes to palm the heavy work off on his much younger wife (Joan Rice); I like to think of them as Burke and Harriet. Understand that Kassner is not happy about any of this. Understand further that Alys is quick to catch on that Victor’s new hobby renders him highly susceptible to blackmail. And don’t forget that one of Frankenstein’s old school chums is a cop these days. All in all, it makes poisoning Elizabeth’s father to obtain a brain for his creature (David Prowse, of Black Snake and A Clockwork Orange) a rather foolhardy thing to do. Before he knows it, Frankenstein is killing practically everyone he knows in the hope of covering his tracks— and the creature, once activated, starts killing everybody Frankenstein doesn’t know, for no apparent reason at all.

Jimmy Sangster was handed the script for The Horror of Frankenstein with the expectation that he’d give it a rewrite. But when he read the screenplay through, he realized at once that it was virtually indistinguishable from the one he wrote for The Curse of Frankenstein back in 1956; what, he rightly asked, was the point of making that movie over again in 1970? Sangster and James Carreras went back and forth for a while about what it would take to interest the former in the project, with the eventual result that Sangster agreed to polish up the script on the condition that he be allowed to direct as well. He’d never done that before, and obviously it would take something out of the ordinary to make rewriting a rewrite of his own work seem like anything but a waste of time. With the whole creative side of The Horror of Frankenstein thus under his control, Sangster was in a position to do the one thing he could think of to justify retelling his old Frankenstein origin story— he’d be able to drastically change its tone. The specific new flavor Sangster had in mind was bawdy comedy, which was indeed about as far from The Curse of Frankenstein as one was likely to get. And since this new Frankenstein picture was to be aimed at the youth market, Sangster would give it a snarky rebellious streak, too.

You can already see what went wrong, can’t you? Because Sangster was adding jokes to a script that didn’t originally have them, the humor never really sits right, even on those far-too-rare occasions when it succeeds in being funny. The bawdiness somehow manages to misfire even more woefully, coming across as merely puerile. Hammer’s approach to sex was always markedly hit-or-miss anyway, but even at their worst, they’d never sunk to this Benny Hill-like level. And what’s really peculiar is, even though sexiness is central to The Horror of Frankenstein’s premise, this is actually a much tamer movie in terms of onscreen content than the typical late-50’s Hammer production, let alone such contemporary offerings as Countess Dracula or The Vampire Lovers. The most absolute failure of all, though, is The Horror of Frankenstein’s bid for youth appeal. Ralph Bates’s performance, for starters, amounts to little more than a poor Peter Cushing impression, except insofar as Bates is self-parodically randy instead of self-parodically chaste. Also, he’s nowhere near charismatic enough to make a good antihero, yet here he is trying to fill the shoes of one of the all-time great antihero players. The intended air of rebellion, meanwhile, is just that— an air which the movie puts on about as plausibly as the insistently Irish Kate O’Mara passes for an Austrian. Finally, Sangster’s attempts at an attitude of ironic bleakness accomplish nothing but to emphasize how square Hammer horror was at heart. It’s hard to put my finger on how or why, beyond to say that gallows humor was not something that Sangster understood how to write or to direct. He seems confused here, too, about where our rooting interest is supposed to lie, and why. Is Victor Frankenstein a magnificent bastard whom we want to succeed despite knowing full well how evil he is? Is he a misunderstood individualist battling the stodgy and hypocritical forces of reactionary authority? Or is he just a straight-up villain, whose comeuppance we await with bated breath as his misdeeds multiply and redouble in severity? Sangster doesn’t apparently know, and none of the other characters have the presence or integrity to take Victor’s place as the center of interest. I guess what it comes down to is that Sangster’s best scripts for Hammer were profoundly moral affairs. Even when they invited us to side with evil (The Revenge of Frankenstein being the starkest example), they were nearly always crystal clear in distinguishing the good guys from the bad. The Horror of Frankenstein wants to be a shades-of-gray movie, but Sangster simply wasn’t a shades-of-gray writer.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact