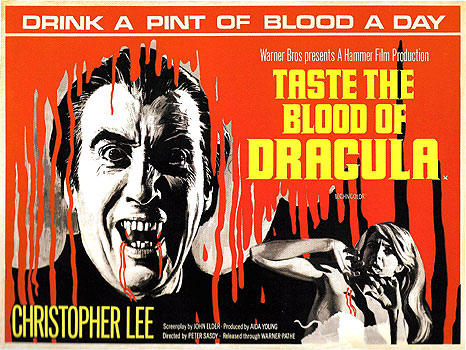

ATaste the Blood of Dracula (1969/1970) ***˝

ATaste the Blood of Dracula (1969/1970) ***˝

It’s too weird and nitpicky a situation to arise very often, but every once in a while, you’ll encounter a franchise entry that so specifically redresses the missteps and misjudgments of its predecessor that it’s almost as if the filmmakers are apologizing to their fans for screwing it up the last time. Taste the Blood of Dracula is one such sequel. It shares all the thematic concerns of Dracula Has Risen from the Grave: hypocrisy, institutional malfeasance and incompetence, generational conflict, good and evil as real metaphysical forces. But whereas the earlier installment was incoherent, reactionary, out of touch with the times, and riddled with hypocrisies of its own, this one is cogent, current, judicious, and if not exactly progressive in its outlook then at least reflective of a more fair-minded conservatism in keeping with the broader Hammer tradition. Its placement in the exact middle of the series is such that it tends to get lost in the crowd, but Taste the Blood of Dracula is probably the best of the bunch, marred only by a weak motivation for the vampire, a conclusion that could have used one more pass during rewrites, and a typically risible performance from Ralph Bates.

For the second time in a row, we begin by rewinding to the timeframe of the preceding movie in order to look in on action that was going on elsewhere. A salesman of knickknacks and bullshit by the name of Weller (Roy Kinnear, from The Bed Sitting Room and The Amorous Milkman) is taking the carriage from Kleinenberg to somewhere else, attempting all the while to unload some of his worthless merchandise on his fellow passengers. Eventually, he so annoys his companions that they toss him bodily from the vehicle, along with all his luggage. Picking his panicky way through the spooky forest flanking the road, Weller stumbles upon the site of Dracula’s most recent demise, just as the undead count (still Christopher Lee— although there’s a story there this time, which I’ll get to in a bit) is dissolving into a foul puddle of viscous gore. The merchant is both suitably impressed and suitably revolted.

Jump ahead five years or so to a Sunday afternoon someplace far more welcoming than the environs of Castle Dracula. In fact, the character names and generally Dickensian milieu here suggest that the series has finally reached London. Church services have just concluded, and teenaged Alice Hargood (Linda Hayden, of Night Watch and Madhouse) is saying a sort of simultaneous hello and goodbye to her boyfriend, Paul Paxton (Anthony Higgins, from Vampire Circus and The Bride), before joining her parents for the coach ride home. Alice should have been more circumspect. Her father (Geoffrey Keen, from Horrors of the Black Museum and Holocaust 2000) throws a four-alarm shit fit back at the house, accusing Alice of profaning the Sabbath with ungodly whoredoms— by which he apparently means speaking to a boy in public. Even Alice’s mother (Gwen Watford, of The Ghoul and one of the more obscure interpretations of The Fall of the House of Usher) thinks Dad is wildly overreacting, but he’s not about to let that rein him in. After Alice retreats to her room for an amply justified sulk, Hargood informs his wife that he isn’t staying for dinner. His philanthropic society is meeting this evening, and he won’t be back until well after his womenfolk have turned in for the night.

Philanthropic society my ass. Hargood and his cronies, Samuel Paxton (Peter Sallis, from The Curse of the Werewolf and Scream and Scream Again)— Paul’s father— and Jonathon Secker (John Carson, of The Man Who Haunted Himself and The Plague of the Zombies), are a wannabe Hellfire Club, and their destination downtown is a high-end whorehouse run by a degenerate homosexual called Felix (Russell Hunter). The men’s orgying does not go quite according to expectations, however, for their privacy is intruded upon by the notorious wastrel Lord Courtley (Bates, from Fear in the Night and The Devil Within Her). Courtley is supposed to be the foremost hell-raiser in town, but Ralph Bates being the soggy twerp that he is, the devilish dandy seems less the Marquis de Sade than the Marquis de Sad. Nevertheless, Hargood, Secker, and Paxton are intrigued by all the fucks Courtley doesn’t give as he barges into their suite and relieves them of their prettiest hooker (Madeline Smith, of Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell and Dr. Jekyll & Sister Hyde). Hargood buttonholes him on his way out the door once he’s finished with Dolly, and invites him to dinner.

Oscar Milde doesn’t take long to figure his hosts out. Gourmets of sin and dissipation, they’ve grown bored at last with the ordinary sort of bad behavior, and now wish for someone to tutor them in advanced wickedness. That’s all well and good, but Courtley doesn’t like having his time wasted by anyone but himself. He challenges Hargood and the others to go big or go home— and going big will not come cheap. Oh, the money isn’t for Courtley— they needn’t worry about that. It’s for paraphernalia, a little something that he saw at an antique shop not long ago, but couldn’t afford on his own resources. You’ll have some idea what Courtley has in mind when the proprietor of the shop in question turns out to be Weller from the prologue. The merchandise His Lordship covets is Dracula’s cape, Dracula’s signet ring, and a vial of red powder that used to be Dracula’s blood. The Heckfire Club still don’t entirely get Courtley’s objective, but a jar full of dehydrated vampire certainly seems to promise exotic enough thrills to suit their jaded sensibilities.

From the shop, the foursome retire to the half-ruined mausoleum of the Courtley family, where the altar of the funeral chapel has already been prepared with an array of Satanic trappings. Courtley means to offer all their souls to the Devil in trade for unspecified supernatural boons, but one doesn’t get Lucifer’s attention by just sending one’s manservant around with a calling card. No, that requires a ritual demonstrating the petitioner’s good-faith commitment to bad faith. Something like reconstituting Dracula’s dried blood and drinking it, for example. That’s right— the title is to be taken literally! But before Hargood, Paxton, and Secker can taste the blood of Dracula, they first must smell the blood of Dracula, at which point all three of them sensibly conclude that this whole soul-selling thing is actually a terrible idea. Incensed, Courtley downs his own goblet of vampire blood, hoping to shame the others into doing what they came here for. However, the way he immediately doubles over in gastric distress doesn’t exactly render his case more convincing. The other men lose their heads as Courtley writhes on the ground in their midst, clutching at their legs for assistance. They begin beating him with their canes in an effort to make him unhand them, not stopping until he ceases moving altogether. And that, or so it would seem, is the end of Dorian Beige.

But is it really? It turns out that drinking Dracula’s blood has effects above and beyond currying favor with the forces of Darkness. It also allows the vampire to reincarnate himself within Courtley’s body. Dracula comes back from the dead rather irritated, though, at the details of his resurrection. I gather that he expected to be greeted by a fawning coven of evildoers— not an empty Satanic chapel— and that Courtley’s death was supposed to have come simply through the toxic effects of the vampire’s accursed blood. Not the sort of man to tolerate being thus slighted, Dracula dedicates himself to the downfall of Hargood, Paxton, and Secker.

Meanwhile, the Heckfire Club find themselves consumed with fear, guilt, and mutual suspicion. Hargood stays drunk practically around the clock, which renders his already winning personality even more delightful. Paxton is virtually paralyzed by worry that Courtley’s body will be discovered, and their crime along with it, yet he can’t bring himself to return to the mausoleum and destroy the evidence. Only Secker keeps his wits about him, but even he is anxious that one of his fellows— the perpetually sloshed Hargood especially— will blab enough of the story to bring the rest of it into the open. So you can imagine how he takes it when Hargood is found dead in his own garden while Alice goes missing.

Actually, the story is more complicated than Secker assumes— or for that matter, than you would expect from a Hammer Dracula movie. Alice disobeyed her father on the night of his death and her disappearance by sneaking out to attend a party with Paul. But when she returned, her father was waiting for her in her bedroom, nursing a stuporous fury and brandishing a riding crop. Hargood was unable to make good on the threat in his impaired state, but did pursue Alice out into the garden. Dracula happened to be out there casing the joint, but rather than fall upon his enemy himself, he imparted to Alice a hypnotic suggestion that there was no time like the present for having it out with her old man once and for all. It was Alice who killed Hargood, striking him down with a shovel and then willingly accompanying the vampire to his lair. Alice is a uniquely good choice for an accomplice, too, because she’s very well connected to all of Dracula’s current targets. Not only is she Hargood’s daughter and the girlfriend of Paxton’s son, but her best friend, Lucy Paxton (Ilsa Blair, from The Monk and the 2005 BBC remake of The Quatermass Experiment), is dating Secker’s son, Jeremy (Martin Jarvis). Through her, the vampire can get to all of his foes’ kids, and through them to the remaining members of the Heckfire Club. On the very day of Hargood’s funeral, Alice coaxes Lucy along with her to the Courtley mausoleum, setting Phase II of Dracula’s revenge in motion.

Meanwhile, Paul is butting heads with a nitwit police inspector (Michael Ripper, of Torture Garden and The Mummy’s Shroud) about the significance of Alice’s vanishing act. Although his stuffy English propriety will not permit him to say so, he knows that Alice hasn’t simply eloped (the inspector’s preferred explanation) because if she had, it would have been with him. Unfortunately, that’s just about the only thing he does know for now. Secker, naturally, has a little more to go on. Proceeding on the assumption that Courtley survived the beating they gave him after all, he leads Paxton on a much belated reconnaissance mission to the crypt, where the two of them stumble upon the now-undead Lucy. Her father is too squeamish to do what needs to be done, and the next thing you know, it’s time for Phase III. Jeremy can expect a visit from Lucy soon, after which Secker can expect a visit from Jeremy. Then it’ll be up to Paul to figure out what’s what before Dracula decides to promote Alice from Renfield to bride.

Taste the Blood of Dracula is a very different movie from the one Hammer initially set out to make. Christopher Lee had been increasingly cantankerous about both his popular association with Count Dracula and the studio’s handling of the character from the moment Horror of Dracula started throwing off sequels. He sat out The Brides of Dracula in a vain attempt to avoid getting typed as a horror star; he vetoed all his dialogue in Dracula, Prince of Darkness, and did nothing but hiss and snarl throughout the whole film; he groused both privately and publicly about the inconsistent and wildly non-standard vampire lore in Dracula Has Risen from the Grave (in which the count casts a reflection and is invulnerable to attack by atheists). Also, Lee was well aware by 1969 of his value as a box-office draw, and felt that it was well past time for Hammer to start paying him accordingly. So James Carreras did what studio bosses usually do with stars who get to big for their britches, and ordered Lee replaced. When Lord Courtley imbibes the blood of Dracula, it was supposed to be merely the vampire’s spirit that passed into him; the body was to remain that of Ralph Bates. But Carreras hadn’t figured on Seven Arts-Warner Brothers, who had distributed the previous Dracula movie in the crucial American market, and were slated to handle this one too. In their reckoning, it was Christopher Lee who sold tickets to Dracula pictures, and not just the character name. Some English TV guy whom nobody had ever heard of was just not an acceptable substitute. Lee’s britches, that is to say, fit just fine, and it was Carreras who ended up needing a new pair.

Normally, you’d consider such serious behind-the-scenes wrangling a bad omen for the completed film. For that matter, the mere presence of Ralph Bates in the cast is usually a bad omen of another kind. So it’s doubly remarkable that this easily overlooked movie is not only a strong contender for best in series, but also the apparent developmental prototype for everything Hammer would get right during their embattled final decade. By starting with Dracula melting into a pool of bloody ooze, and by introducing Lord Courtley in a whirlwind tour of Felix’s brothel (the latter a sequence which was detrimentally trimmed from US theatrical prints), Taste the Blood of Dracula raises the gore-and-titillation ante to a level competitive with contemporary productions overseas. By inserting Dracula into the middle of a conflict between hypocritical elders and unjustly vilified youth, it creates for itself a framework in which to engage the issues of its day without getting lost in doomed attempts to portray a youth culture that its makers don’t understand (a technique that would subsequently be used to even greater effect in Twins of Evil). And with its handling of Alice and Paul— especially during the regrettably muddled and bewildering climax— it takes up in a much more thoughtful and sophisticated way its predecessor’s question of what it means to be good or evil in a society that can no longer trust its institutions.

The crux of the film, and the moment which best demonstrates its strengths, is the sequence culminating in the death of William Hargood. Knowing what we do of him, it’s impossible not to recognize the corrupt lust spilling out on a wave of alcohol as he advances on his daughter with that whip. This confrontation has been building, we sense, since the day Alice’s figure began to fill out. When she flees into the garden and runs straight into Dracula’s arms, it plays out not like a capture, but like a narrowly won reprieve— and then the scene grows more subversive still when the vampire doesn’t lay a finger on Hargood, but rather directs Alice to pick up that shovel and come to her own rescue. Dracula knows what girls like Alice need. Even more startling is the realization that creeps up on you as the closing credits roll: she is never punished for killing her father, nor for any of the other things she does under Dracula’s influence! This despite an ending at least as overtly religious as the last film’s, in which the key factor appears to be Paul’s do-it-yourself re-consecration of the vampire’s lair. In sharp contradiction to Dracula Has Risen from the Grave, Taste the Blood of Dracula implies a God with extremely nuanced ethics.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact