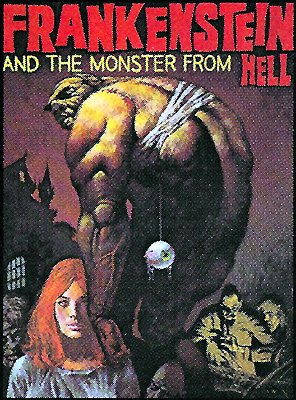

Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell (1974) ***

Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell (1974) ***

As titles go, Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed sounds pretty fucking final, and there are indeed plenty of indications that Hammer intended it to be the last of the line. There was the tagline, for example: ďFrankenstein Must Be Destroyed! The screenís most fantastic fiendÖ and Hammer say so!Ē The ending, too, left Victor Frankenstein in a situation that any man would be hard pressed to escape from alive, with the former colleague whose brain he transplanted without permission into somebody elseís body dragging him unconscious into a furiously burning building. And perhaps most decisively, the next Hammer Frankenstein film was not a fifth sequel to The Curse of Frankenstein, but rather a relaunch of the franchise, with a different, much younger actor taking over Peter Cushingís accustomed role. The Horror of Frankenstein was not a notable success, however, and Hammer made no Frankenstein movies at all for three years; to grasp the significance of that delay, consider that the studio released no fewer than four Dracula installments between 1970 and 1973! In 1974, however, the increasingly embattled studioís leadership gambled that it would put the company back on track to resurrect the formula that had made them great in the first place: Cushing building a proper monster in the grisliest manner that the censors would allow. A conscious return to Hammerís roots might have pleased the longtime fans, but the inability to grow beyond those roots in a saleable, relevant way was precisely Hammerís problem in the 1970ís. Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell, for all its seeming promise, wound up looking very much like the throwback it was, and its era was not a forgiving one for throwbacks. Today, though, this filmís unusual mixture of stodgy traditionalism and raw 70ís viciousness looks substantially more appealing than it must have in the days when it was the best riposte its producers could think of to the challenge posed by Night of the Living Dead, The Exorcist, and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre.

Someone who never saw the trailers and took their seat too late to catch the credits could be forgiven for assuming at first that this was actually a sequel to The Horror of Frankenstein, for although the mad scientist who takes delivery of a dead body from a grave-robber in the opening scene isnít Ralph Bates, he is another of the not conspicuously deserving young actors whom Hammer spent the 70ís pushing in the hope of creating a bankable new star or two. This kid isnít Frankenstein, however, but Simon Helder (Shane Bryant, from Captain Kronos, Vampire Hunter and Straight On Till Morning). Nevertheless, there is a connection, in that foremost among the books strewn over every table and bench in Helderís garret laboratory is a bound collection of all Baron Victor Frankensteinís published papers on medicine and anatomy. Also, Simon is no more popular with the authorities than his notorious idol, and the next visitor he receives is a policeman who places him under arrest for sorcery. The trial goes relatively well for the defendant, I supposeó at least thereís no gallows or guillotine in his future. Instead, the young medical miscreant is sentenced to five years in a hospital for the criminally insane, at the end of which he is to be evaluated once again to determine whether he has been rendered fit to reenter society.

Mind you, thatís likely to be plenty bad enough. Val Lewtonís Bedlam looks like Monte Carlo next to the place where Helder gets sent. Hans (Christopher Cunningham, of Lust for a Vampire and Dracula Has Risen from the Grave) and Ernst (Philip Voss) the orderlies are right brutal bastards who like to entertain their charges by herding them all in to watch while they give new arrivals a firehose bath and an introductory beating. The asylum director (The Witches of Pendleís John Stratton) is a pompous, stupid, and corrupt man who, if left to his own devices, would no doubt be content to toss his patients down an oubliette to starve, and Helder gets on his bad side immediately by temporarily hoodwinking him into taking him for a guest rather than an inmate upon their initial meeting. Even Helderís one major hope for his term of confinementó for he knows that this is the very same hospital in which Baron Frankenstein was finally locked awayó is dashed when the director informs him that Frankenstein died years ago, and now lies buried in the backyard cemetery.

Very well, but if thatís so, then what the hell is Peter Cushing doing skulking around the asylum, upbraiding the staff and taking notes on the patients? He may call himself ďDr. Victor,Ē but that poncey blond wig (easily the worst thing a wardrobe or makeup department has ever foisted on Cushing) isnít fooling me. It will eventually come to light that Frankenstein, even in captivity, was too clever by half for his enemies. He quickly got wind of the directorís habitual misappropriation of asylum funds, and of a secret regarding the connection between him and a patient named Sarah (Madeline Smith, from Some Like It Sexy and Theater of Blood) that would prove instantly fatal to the directorís career (if not indeed to the director himself) if it ever got out. Armed with such information, it was a simple matter for Frankenstein to arrange both the faking of his own death and the installation of the fictitious Dr. Victor as the asylumís top doc. Frankenstein now runs the place for all practical purposes, regardless of what the shingle on the directorís office door might say. Itís only to be expected that Frankenstein would take an interest in Simon Helder, nor should we be surprised that Helder is the one person who has no trouble seeing through the baronís disguise. Very shortly after the younger manís admission, Frankenstein takes him on as an assistant, with the aim of palming off on him as many of the day-to-day duties for the inmatesí care as possible. Frankenstein himself inevitably has other work heíd rather be doing.

There is a special ward in the asylum where Frankenstein keeps inmates who particularly engage his curiosity, which at present is home to three quite remarkable men. Professor Durendel (Charles Lloyd Pack, of Old Mother Riley Meets the Vampire and Corridors of Blood) is a musical and mathematical genius who seems to have suffered what we would describe today as a nervous breakdown. Heís perfectly lucid, and the only thing visibly wrong with him is a crippling lack of coping skills, but Frankenstein claims to see little prospect of him ever again being able to function outside of the asylum. Tarmut (Bernard Lee, from Itís Not the Size that Counts and Dr. Terrorís House of Horrors) is a sort of idiot savant of sculpture. He has the mind of a frightened child, but the things he can make with his hands, even under the rudimentary conditions obtaining in his cell at the asylum, are extraordinary. And then thereís Schneider. Frankenstein describes him as an evolutionary throwback, more animal than man, possessed of nearly superhuman strength but incapable of speech, reasoning, or problem-solving at any higher level than ďHULK SMASH!!!!Ē Schneider is the only one of Frankensteinís special patients whom Helder doesnít get to meet during his orientation tour, because the beast-man mortally wounded himself a few nights ago while breaking out of his cell; seeing the damage he did to the outside wall, itís easy to imagine that the breakout would have left him in straits every bit as dire. This is a Frankenstein movie, though, so it will come as no surprise when we learn that the baron saw to it that Schneiderís body was not disposed of in the regulation manner, transferred instead to the secret laboratory he maintains behind his office in the asylumó a lab, by the way, which does not remain secret from Helder for long. Schneider (David Prowse, of Vampire Circus and Jabberwocky) lives again, but with blinded eyes and pulped hands on top of his congenital mindlessness, he is hardly a satisfying research subject for Frankenstein in his current state.

Those of you who remember the first two films in the series will have already guessed what the baron is about to get up to. As in The Revenge of Frankenstein, heíll be harvesting the choicest parts from the powerless men under his care, and as in The Curse of Frankenstein, the operative theory behind his monster-making is to upgrade an exceptionally powerful body with the means to bring it mentally, perceptually, and dexterously up to the same standard of exceptionality. Both Tarmut and Durendel succumb to extremely convenient deaths in the coming days, and itís the former manís funeral that spurs Helder to seek out Frankensteinís lab and to volunteer himself as a collaborator in his heroís secret work as well. Certainly Frankenstein could use the help, as screenwriter Anthony Hinds (unlike the writers of Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed) remembers that the renegade scientist lost the use of his hands when his lab blew up in The Evil of Frankenstein. Sarah has thus far performed admirably under the baronís guidance (and isnít it just like Frankenstein to pick the hysterical mute to do the work he wouldnít want anyone to know about?), but sheís obviously no substitute for a trained surgeon. Soon, Frankenstein and Helder have Schneiderís body outfitted with Durendelís brain and Tarmutís hands and eyes, and the baron is hard at work devising a therapy program to get all the disparate parts working in proper concert. The thing about being cooped up in the asylum, though, is that Frankenstein doesnít have the option of vetting his ďdonorsĒ for tissue compatibility, and it turns out that Durendel and Schneider arenít a good match at all. The brilliant, sensitive mind that the baron so coveted for his creation quickly goes rotten and deranged, and itís only a matter of time before the composite superhuman lapses into brain death. And more importantly, itís only a matter of time before an insane ex-genius who now has the strength of a grizzly bear thinks to use that strength when something pisses him off.

Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell is not a very well-reputed movie, often regarded as one of the worst of the series. Iíll agree with that as far as it goes, but not because this film is at all bad on the whole. Itís just that four of the preceding five installments are so great that a generally competent 70ís update of the standard Frankenstein movie premise has to be regarded as a significant comedown. The trouble with Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell is basically that weíve been through this before. It wasnít as bloody or as gritty or as thoroughly misanthropic back in the late 1950ís, but the only really new ground being broken here is the truly terrible monster costume that David Prowse must contend withó a costume rendered doubly unfortunate by the way you can dimly make out how hard Prowse is striving to get some real acting done underneath it. The aim was obviously to make Prowse resemble some sort of hulking protohuman, but the execution is in some ways even worse than the titular creature in Trog. Otherwise, I find very little to complain about in Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell. Cushing is brilliant as ever, and seems to be channeling his despair over the recent demise of his wife into a Frankenstein who, though still swelling with defiant hubris, recognizes at some deep-seated level that he has finally been defeated by the society he holds in contempt. After all, what can he really accomplish, in light of the lofty aims he proclaimed in Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed, by whiling away his remaining years rearranging the bodies of lunatics? Frankenstein, to all appearances, is no more satisfied with his return to well-covered ground than the audience is likely to be, and that goes some way toward making up for the retreading. The relationship between Frankenstein and Helder is well drawn, and keeps the viewer constantly gnawing at the question of which man is the bigger psychopath. There are a few aggressively gruesome scenes which prove that Hammer could still steal a march on the competition when they felt like it, an impressively staged set-piece with the monster rampaging through the asylum cemetery in search of its several graves, and the most pitch-black bit of physical comedy this side of Frankenhooker. But most of all, Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell lives up to the best tradition of its franchise, the sense that these movies (with the unfortunate exception of The Evil of Frankenstein) collectively convey of a single, consistent developmental arc for the title character, no matter how many of the little details might get lost or reinterpreted along the way. Victor Frankenstein each time is a somewhat changed man, and each time (with, again, that one exception), thereís a clear reason for the nature and direction of the change. In that sense if no other, Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell is a worthy capstone for the series it brought to a conclusion.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact