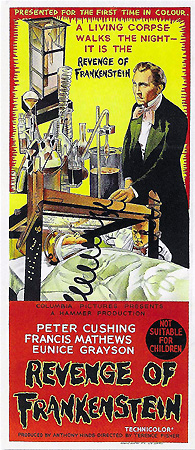

The Revenge of Frankenstein (1958) ****

The Revenge of Frankenstein (1958) ****

To anyone who fails to comprehend my very strong preference for Hammer Film Productions’ 50’s- and 60’s-vintage remakes of such mildewy horror classics as Frankenstein and Dracula to the Universal Studios versions of the 30’s and 40’s, I would like to say two things. First, and of less importance, I call your attention to the fact that with one woeful exception, Hammer had the class not to play their rapidly aging horror franchises for laughs when their popularity declined in the 1970’s. (And a good thing, too-- you’re a harder-core devotee of sewage cinema than I if your blood doesn’t turn to ice at the prospect of Benny Hill Meets the Mummy.) As for my second point, let me steer you in the direction of The Revenge of Frankenstein. This first sequel to The Curse of Frankenstein serves as a perfect example of Hammer’s boldness in re-interpreting stories and characters already deeply entrenched in the myth-pool of the 20th century, often in ways that fly directly in the face of audience expectations. Let’s face it; everybody knows Frankenstein and his monster, but most people know them not from Mary Shelley’s novel, in which their story first appears, but rather from James Whale’s 1931 movie. Say “Frankenstein,” and most people will instantly think of Boris Karloff in a squared-off headpiece and platform heels, and of Colin Clive gasping, “It’s alive! It’s alive!!!!” And the fact of the matter is that most screen adaptations of the story owe far more to Whale’s film than to Shelley’s book. When The Curse of Frankenstein was made in 1957, Universal’s jealousy of their copyright prerogatives essentially forced Hammer to steer clear of anything that suggested Jack Pierce’s makeup or Karloff’s portrayal of the monster, but the tack taken by the English studio for the prolific run of sequels cannot be so easily written off as the product of lawsuit-phobia. Universal’s Frankenstein sequels focused primarily on finding excuses to bring the creature back to life, usually involving the activities of descendants of the original mad doctor. Hammer’s approach is far more interesting, and is, in its way, truer to Shelley’s vision of what the story was about. Instead of chronicling the exploits of the monster, the Hammer movies follow the career of Baron Frankenstein as he continues his efforts to perfect his technique for breathing life into re-constituted corpses.

The Revenge of Frankenstein picks up more or less where The Curse of Frankenstein left off, with Baron Frankenstein (Peter Cushing again) facing execution for the crimes committed by his creature in the last film. As is so often the case with sequels, however, there are a couple of points of discontinuity. First, the new movie wisely disregards the turn into darkness for its predecessor’s ostensible hero implied by The Curse of Frankenstein’s epilogue. I say “wisely” because to do otherwise would only have cheapened that ending by destroying the air of subtle understatement that gives it its power, while simultaneously cheapening the sequel by pushing it into the hackneyed territory that most of the Universal Frankenstein movies occupied. Secondly, you may recall that the last movie had Frankenstein accused of committing his creature’s murders himself, and that his incredible tale of a homemade monster was reckoned to be proof of his madness. The Revenge of Frankenstein has the baron become an internationally renowned villain for his tampering in God’s domain, and the charges against him explicitly recognize that he is being held accountable for his monster’s misdeeds. But Frankenstein is, after all, a genius, and he left his last scruple behind him when he murdered to obtain a brain for his creature. It is thus less than surprising to see the baron turn the tables on his would-be executioners, arranging for the replacement of the men operating the guillotine with two of his agents, who, at the last minute, force a convenient priest into the machine instead. The next night, Frankenstein and his lackeys hire a pair of petty criminals to dig up the grave that supposedly contains the doctor’s body (the coffin, of course, actually houses the dead priest) to provide fresh materials for another attempt at creating life.

Three years go by, and Frankenstein (under the name of “Dr. Stein”) relocates from his native Switzerland to Carlsbruck, Germany (in which case it ought to be “Karlsbruck,” but the signs and title cards in the movie all spell it with a “C” so what the hell), where he has set up a thriving medical practice, siphoning away patients from all the local doctors, while simultaneously operating a public hospital for the poor. The fat-cat neighborhood doctors are all incensed by this turn of events, which is made even more biting for them by Frankenstein’s refusal to join their monopolistic association. The final insult that will earn the baron the eternal enmity of his “colleagues” comes on the day that the president of the society (Charles Lloyd Pack, from Horror of Dracula and The Reptile) sends a delegation around to bully Frankenstein into joining them, and the contemptuous baron makes them wait for him in the public hospital’s main ward, surrounded by evil-smelling, flea-bitten indigents. This is going to come back to haunt Frankenstein, mark my words.

But not all of the local doctors feel threatened by “Dr. Stein.” One, a certain Hans Kleve (Francis Matthews, who would show up later in Dracula, Prince of Darkness and Rasputin, the Mad Monk), actually sees the man’s presence in Carlsbruck as an opportunity. Kleve, you see, thinks he knows who “Stein” really is, and he is quite confident that he can blackmail the doctor into teaching him all about his ungodly research. Kleve’s instincts are right on the money, not only as regards the new doctor’s true identity, but also in the matter of his susceptibility to blackmail. Frankenstein agrees, somewhat reluctantly at first, to take him on as a pupil, but it rapidly becomes clear that Kleve is at least as talented as his old accomplice Krempe, and the baron swiftly finds all sorts of uses for him. The current project makes Frankenstein’s initial efforts look like the work of a talented child with his first Erector set. It is the doctor’s intention to transplant the brain of his assistant, Karl-- the right side of whose body was paralyzed by a blood clot-- into the new body he constructed over the past three years. (Post-transplant Karl is played by Michael Gwynn, whose acting credits range from Jason and the Argonauts to Village of the Damned to The Deadly Bees.) This is no monster, either, all glazed eyes and oozing sutures. This time, Frankenstein has achieved something very much like the perfect facsimile of a man that had been his goal all along. Karl has agreed to donate his brain in the hope regaining the life he led before his illness crippled him, and when the transplant is performed, it certainly looks like a success.

But nothing is ever that easy in a horror movie, and Karl’s body-switch is no exception. His problems stem ultimately from the fact that it takes some time for a brain to adjust to living in a new body. Frankenstein’s earlier experiments with reptiles and apes suggest that at least a week or two of more or less total inactivity is required for the transplant to take. Thus Karl spends his first several days in his new body strapped to a bed in the hospital attic. Deep down, Karl knows this is for his own good, but that doesn’t make him any less itchy to get up and take himself for a test drive. And conveniently enough, a soft-hearted woman named Margaret Conrad (Eunice Grayson, who would appear in several James Bond films in the 60’s), who recently began working at the hospital, has it brought to her attention that there is a man strapped to a bed in a secret, locked room in the hospital. She goes to check it out, and discovers Karl, whose restraints she helpfully loosens, allowing him to free himself after she leaves.

This is very bad business, because anything but the strictest adherence to Frankenstein’s regimen will seriously endanger Karl’s proper recovery. To begin with, Frankenstein’s research has shown that the brain is fundamentally conservative, and will try to follow its accustomed habits unless great effort is expended to break it of them. For Karl’s purposes, this means that, without the baron’s intervention, his brain will most likely fall back into the habit of paralysis, even though there is nothing physically wrong with his new body. More ominous is the possibility suggested by the experience of Otto, Frankenstein’s chimp with an orangutan brain. Shortly after his operation, Otto suffered a stress-related brain injury that turned him into a cannibal. (The movie stumbles here. The set-up for this revelation hinges upon Kleve’s observation that Otto anomalously eats meat. Puzzled by this aberration, he asks Frankenstein to explain. The problem here is that chimps are not in fact strict herbivores. Indeed, they often hunt monkeys, in an astonishingly human-like fashion, for their meat, and under rare circumstances, they may even practice cannibalism. All of this happens in the wild, and no orangutan-brain transplant is necessary to bring it about.) And wouldn’t you know it, Karl’s escape from the hospital has the effect of putting him in some very stressful situations.

But that may actually be the least of Frankenstein’s worries. Remember my promise that the baron’s antagonistic attitude toward the medical society would come back to haunt him? Well, it’s at about this point in the movie that its members come into possession of evidence suggesting that their nemesis Dr. Stein may, in fact, be the notorious Dr. Frankenstein, and they waste no time getting around to making his life very difficult on this score. It isn’t until word gets out into the community as a whole, though, that Frankenstein faces any real danger. What do you think might happen if the charity cases he’s been carving up for parts get wind of this particular rumor, eh?

My point is that this is a movie with balls. Faced with the opportunity to follow Universal’s lead and begin cranking out movies in which Christopher Lee (or a Glenn Strange-like Imposter of the Week) would be resurrected again and again by descendants of his creator to stagger around for 90 minutes until being set alight by yet another enraged mob, the makers of The Revenge of Frankenstein chose instead to take the story in a hitherto-unimagined, radical new direction. There isn’t even really a monster in this movie, as Michael Gwynn’s makeup is restricted to a gradually diminishing scar on his forehead, and he plays the part as that of an essentially normal man whose mind is coming unhinged due to circumstances beyond his control. And then there’s the ending. It may lack the confident restraint of The Curse of Frankenstein’s concluding whammy, but that is more than made up for by the fact that, in the mad scientist sub-genre, only Re-Animator can match the finale of The Revenge of Frankenstein for sheer nerve.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact