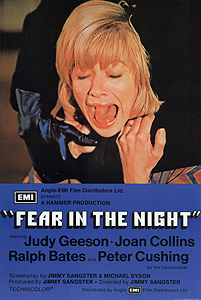

Fear in the Night / Honeymoon of Fear / Dynasty of Fear (1972/1974) **½

Fear in the Night / Honeymoon of Fear / Dynasty of Fear (1972/1974) **½

Oh, hey— would you look at that? It’s another early-70’s Hammer film that points down a promising path not taken, or at least not taken far enough to keep the company alive against declining interest in opera-caped vampires and mitteleuropäischen mad scientists. The last of Hammer’s mini-Hitchcocks, Fear in the Night hints maddeningly at a parallel timeline in which one can speak instead of a transition from mini-Hitchcocks to mini-Argentos. A lingering British squeamishness about really explicit bloodshed prevents it from being truly state of the art, but other details like a killer with a prosthetic arm and a school attended only by the recorded voices of long-ago students place Fear in the Night as close to the newly prolific gialli as to earlier Hammer psycho-horror pictures like Scream of Fear or Maniac.

Fear in the Night’s heroine, however, is right out of those old movies. Her name is Peggy Heller (Judy Geeson, from Inseminoid and It Happened at Nightmare Inn), and she has a history of nervous breakdowns. She’s also just gotten rashly married to a man she’s known for only three months. Robert Heller (Ralph Bates, of Persecution and Lust for a Vampire) seems like a nice enough bloke, but this is a genre in which looking before you leap is very strongly indicated. Robert lives in a cottage on the grounds of the boys’ boarding school where he teaches, which means that Peggy will soon be living there, too. It’s a familiar Gothic setup, but in this case, the threatening weirdness doesn’t even have the decency to wait until the girl is ensconced in unfamiliar territory to break out. On Peggy’s last night at the home of Mrs. Beamish (Gillian Lind, from …And Now the Screaming Starts!), the old lady whom she’d been serving as a live-in maid, she is attacked by someone in a black overcoat, who attempts to strangle her from behind. The last thing Peggy observes before she blacks out is that her assailant wears a hook-handed prosthesis in place of his left arm. But when she comes to a little while later in Mrs. Beamish’s parlor, she is unharmed, there’s no sign of any one-armed maniacs, and Robert, Mrs. Beamish, and the local doctor alike act like they’re more worried about her mental state than they are about the prospect of errant giallo killers setting up shop in England.

Naturally there’s more of the same in store after Peggy moves in with her husband. That school where Robert works is an eerie place. The complete absence of students is innocent enough, since they’re between terms at the moment, but if Robert has to report to campus in preparation for the coming semester, then shouldn’t there be some other faculty and staff on the premises? And given the emptiness of the facility, doesn’t it seem weird that the beds in the dormitories and infirmary are all made, and the tables in the dining hall all set for dinner? Shouldn’t the linens and dishes be kept in storage until someone was around to use them, so as to prevent them gathering dust? Then there’s Michael Carmichael, the headmaster (Peter Cushing). He’s friendly enough when Peggy meets him by accident while poking around in the school, but he’s also… I don’t know. Spacey. Out of phase with his surroundings. If he weren’t a headmaster, you’d swear he was hopped up on something. And his preferred method of getting ready for the arrival of his pupils is unsettling. Peggy makes his acquaintance by following the sound of boisterous young voices, until she inadvertently barges in on him lecturing to an empty classroom where a recording of rowdy children plays over the PA system. Oh— and it’s worth pointing out that Carmichael has both a penchant for black overcoats and an artificial left arm. His wife, Molly (Joan Collins, from The Devil Within Her and Terror from Under the House), is pretty creepy, as well. She’s one of those B-movie hunters who don’t trouble themselves overmuch about whether there are people in the line of fire when they take down their quarry, and who delight in confronting the squeamish with the violent deaths of small, inoffensive animals. Peggy is as squeamish as they come, and Molly practically tortures her with that bunny she shoots in front of her the first time they cross paths.

All of which is pretty much a roundabout way of saying that Peggy has plenty of reasons to be off her game when the One-Armed Strangler starts coming round at the school and the cottage. And just like before, Robert’s response to his wife’s reports of being stalked by a would-be murderer is the farthest thing from helpful. In fact, it’s so far from helpful that you’d be inclined to suspect him of being involved in some kind of conspiracy against her even if you hadn’t already been cued to expect such dirty dealing by the plots of virtually every Hammer psycho-thriller since at least The Snorkel. When the details of the scheme emerge, it’s nice to see that we’re dealing with something more idiosyncratic than the well-worn old Gaslight routine, even if it does resemble Nightmare just a little too much to qualify as original. As in the latter film, Peggy is the target of the plot only insofar as a weaponized crazy person comes in handy for directing blame away from the real conspirators when people start turning up dead. Having said that, I’ve as much as told all but the least perceptive of you the secret, so I might as well spell it out: Robert and Molly are having an affair, and they’ve been faking the attacks on Peggy in the hope of driving her to kill Carmichael for them. Their plan has two flaws, however. First, Carmichael isn’t half as addled or senile as he looks, and secondly, they’ve underestimated Peggy even further.

I can understand why Hammer gave up on psycho-horror after Fear in the Night. In many respects, this movie looks like the dying gasp of an obsolete genre. The storyline is far too familiar; the small cast by itself will blow the mystery for anyone actively trying to outguess the screenwriters; and the whole film has a listless quality similar to that of Jimmy Sangster’s other directorial projects, The Horror of Frankenstein and Lust for a Vampire. The latter defect especially is absolutely toxic to suspense, which of course is rather a problem for a suspense movie. Peter Cushing is largely wasted, Ralph Bates continues to disappoint, and Joan Collins is merely meta-interesting, noteworthy only because of the brilliant hucksters who later took her presence in the cast as an excuse to reissue Fear in the Night as Dynasty of Fear. But Fear in the Night has something that Hammer sorely needed in 1972. It has style, and style of a sort that doesn’t just hearken back to the studio’s rapidly receding glory days. Its weird, gimmicky killer (or at any rate, the weird, gimmicky character we’re supposed to think of as the killer) is, if anything, a few years ahead of the curve, and Sangster’s willingness to give disorienting imagery preference over conventional story logic could have made Fear in the Night a big hit on the Continent if it were paired with the same “fuck the censors” attitude that had animated Hammer’s first generation of gothic horror films in the late 1950’s. Although inescapably a very minor movie— even more so than its predecessors in the cycle of mini-Hitchcocks that it brought to a close— Fear in the Night is still worth a look as an example of promise unfulfilled.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact