Gaslight / Angel Street / A Strange Case of Murder (1940) ****

Gaslight / Angel Street / A Strange Case of Murder (1940) ****

The malignant, acquisitive scuzzbucket attempting to drive a rich lady insane for fun and profit has long been among the most popular driving forces for suspense movies, and for nearly as long, the 1944 Ingrid Bergman vehicle, Gaslight, has been considered to be the definitive example of the form. That movie may indeed deserve the honors it is conventionally accorded (in fact, we’ll be turning our attention to that very question in the not-too-distant future), but what its boosters often lose sight of— and in some cases, may not be aware of at all— is that the 1944 Gaslight is a remake of an earlier and now all but forgotten film. Four years before MGM, British National adapted the same story (derived from a stage play known as Angel Street on the western shore of the Atlantic) to the screen with such impressive results that the present-day obscurity of their version seems a nearly criminal injustice.

Late one night in 1865, a man breaks into the mansion at 12 Pimlico Square, and murders Alice Barlow (Marie Wright), the immeasurably wealthy old lady who leases the house. Mrs. Barlow’s killer then frisks the dead woman’s body, but evidently he does not find what he hoped, for he soon dumps her onto the floor and slits open the upholstery of the chair in which she had been sitting. Still thwarted, he sets about systematically ransacking the entire house, emptying cupboards, dismantling chests of drawers, and shredding every pillow, bolster, and seat cushion he can find. The article in the next day’s morning paper which reports the crime may state that the Barlow Rubies were missing from the mansion when the police came to investigate, but something about the killer’s body language as he makes his escape tells me that it isn’t because he succeeded in absconding with them.

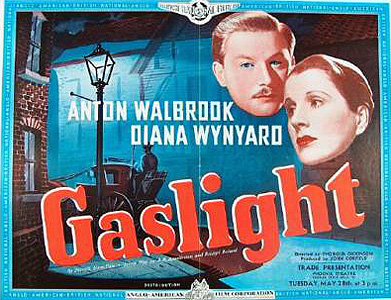

Twenty years later, 12 Pimlico Square finally gets a new tenant— or two tenants, to be precise. The couple who move into the long-abandoned house are Paul Mallen (Anton Walbrook, from the 1935 version of The Student of Prague) and his mousy and noticeably unbalanced wife, Bella (Diana Wynyard). The new tenants keep mostly to themselves at first, and it’s pretty clear that the reason why is that Paul fears his wife will do something to embarrass him if he takes her out in public. They do go to church, at least, and it is on their way home one Sunday morning that they catch the eye of B. G. Rough (Frank Pettingell, from Corridors of Blood), who runs the livery stable not far from the cathedral. Rough used to be a policeman before he got a little too old to go picking fights with felons, and he’s positive he’s seen Paul Mallen before. In fact, he takes Mallen to be a man called Louis Delgado, who was the rather notorious ne’er-do-well nephew of the late Alice Barlow. Rough’s assistant, Cobb (Jimmy Hartley, of Satellite in the Sky and The Lost Continent), however, tells him otherwise— and he should know, too. After all, Cobb is one of several men who are currently competing for the romantic attentions of the Mallens’ chambermaid, Nancy (Cathleen Cordell). Still, Rough thinks he smells a rat, and the old habits of crime-solving evidently die hard. He asks Cobb to keep an eye on Number 12, and to discreetly pump Nancy for any information she might have about her employers.

Rough is right to be suspicious. Paul Mallen is indeed the man he knew as Louis Delgado, and he’s up to something so nefarious that Rough would scarcely believe it if somebody just flat-out told him. Mallen, you see, had always been the poor relation in his family, and he was almost psychotically resentful of his aunt’s wealth. He— as you’d have guessed very swiftly even if I’d kept my big mouth shut— was the one who killed Alice Barlow twenty years ago, but he never did locate the jewels that motivated his crime. Many years later, he married the richest young woman he could find, in order to use her fortune to gain access to his dead aunt’s old mansion. That his new wife should turn out to be nervous, weak-willed, and easily dominated was simply the icing on the cake. The theory underlying Mallen/Delgado’s scheme, of course, is that those rubies are still in the house somewhere, and that by taking up residence at 12 Pimlico square, he can comb the building for them at his leisure. To that end, he has deliberately allowed the upper two floors of the mansion to remain derelict, and he has also arranged to lease the house next door on the sly, so as to both cut down on the number of potential witnesses to his activities and provide himself with a staging area for his nocturnal explorations upstairs. After all, it just wouldn’t do to have Bella see him spending so much time in the theoretically disused section of the house, and Number 14 has a widow’s walk surrounding the loft which allows ready access to the corresponding floor of Number 12.

Even so, there is a potentially crippling hole in Paul’s plan, in that shortly before the move to Pimlico Square, Bella accidentally stumbled upon a letter addressed to Louis Delgado while straightening her husband’s desk. Bella, of course, had never heard of Louis Delgado, and she became sufficiently curious about the mysterious envelope to ask Paul about it. Had she thought instead simply to read that letter, the game would have been up right then and there, and Paul isn’t about to risk discovery again. To that end, he has taken advantage of his wife’s history of psychological instability to plant the idea in her head that she is once again teetering on the brink of madness. The first thing he did was to convince Bella that she merely dreamed or imagined the whole incident with the letter. That accomplished, he now concentrates on keeping her constantly off-balance and second-guessing herself. He pockets small items from around the house, plants them in places to which an “objective” observer would expect Bella to have the easiest access, and then makes a big production of “discovering” them, painting his wife as a kleptomaniac. Bella naturally has no memory of committing these irrational acts of petty pilfering, but neither would she ever think of suspecting her husband, and both Nancy and her fellow maid, Elizabeth (Minnie Rayner) can make perfectly convincing cases for their own innocence (which is only to be expected, seeing as both women really are innocent). The key to Paul’s scheme is that Bella remembers well her previous brushes with mental illness, and thus takes relatively little persuasion to imagine that her grasp on reality is slipping again. It isn’t just Bella herself whom Paul wants to convince of his wife’s madness, however. No, if he’s ever to be really safe from discovery, he has to get everyone in his social orbit to believe she’s nuts, too— that way nobody will credit her story in the unlikely event that she finally works up the nerve to try to dig up and expose Paul’s secret identity and the twenty-year-old crime that goes with it. Needless to say, a nosy ex-cop like B. G. Rough is going to play havoc with any such endeavor, and the interference of Bella’s relatives back home— her cousin, Vincent Ullswater (Robert Newton), especially— would be an even more serious threat. So there’s going to be big trouble ahead for Mallen when Rough picks up enough hints of foul play to seek out Ullswater himself.

You’re not going to find many purer examples of the psychological thriller than Gaslight. Indeed, matters of clinical psychology are central to nearly every aspect of the story. But what is not as immediately obvious is that Gaslight draws just as heavily on the other major branch of behavioral science— it could fairly be described as a sociological thriller, too. For though Mallen’s plot against his wife seeks primarily to exploit her history of mental instability, he would never have the slightest hope of getting away with it were it not for the enormous power imbalance between husbands and wives in the Victorian age. It really is an extremely ambitious scam Mallen’s running here, after all, requiring him to manipulate and control almost every facet of Bella’s life. He has to keep her from having any unexpected contact with people who might be able to expose his lies. He must maintain complete mastery over the couple’s social affairs if he’s going to continue to manufacture incidents with which to present his wife as a madwoman in the eyes of their acquaintances. Most importantly, he needs to dictate all of Bella’s movements, to tell her when, with whom, and under what circumstances she’ll so much as leave her bedroom. Fortunately for Mallen, an upper-class Victorian man could do all those things and more with the woman he had married. So while it is Bella’s mind on which her husband sets his sights, it is the Victorian social context that makes it possible for him to achieve his evil aims.

All things considered, there’s a fair chance that Gaslight is the finest British suspense movie of the 1940’s. At the very least, it’s the best I’ve seen by a comfortable margin. For my purposes, its most appealing feature is its refusal to play by the rules of the mystery, the formula to which it might most logically be expected to adhere given both its subject matter and its time and place of origin. Instead, Gaslight is among the earliest fully modern suspense films, emphasizing an in-depth psychological examination of both villain and victim over the heroes’ efforts to catch the former and rescue the latter. This can be seen most obviously in the way the movie reveals almost immediately that Paul Mallen is a slimy, evil man, even if it takes a little while before it comes out just how evil and slimy. Letting the audience know from nearly the beginning the approximate nature of the threat to the heroine, and exactly the direction from which it will come, focuses the movie’s energy in a way that was all too rare in the 40’s, and provides a fine illustration of Alfred Hitchcock’s bomb-under-the-table principle.

Also worthy of note is how blessedly free of plot contrivances Gaslight is. Most movies which revolve around the sort of Wilkie Collins-ish trickery that Paul Mallen seeks to pull on his wife wind up piling on the coincidences until they’re practically standing in line to trip the viewer’s anti-bullshit circuit breaker. Not Gaslight. The only coincidence here is the one that sets the main story in motion, when it just so happens that a retired cop who knew Mallen years ago under his real name is now employing one of several suitors to the girl who works as the Mallens’ chambermaid. And in a world that is willing to award classic status to the works of brazen and unrepentant coincidence-mongers like Thomas Hardy, that really isn’t too big a demand to make on audience credulity.

The brightest jewels in Gaslight’s crown, however, are the performances of the three lead actors. Frank Pettingell hits the perfect note of time-honed cunning and rusty bluster as B. G. Rough; he’s exactly what you want to see in a tough old former cop who can’t quite let go of his erstwhile duty to protect the innocent from the bad guys. On the opposite side, Anton Walbrook confidently steers the necessary middle course that paints Mallen as a total heel while still leaving it plausible that most of the outside world could fail to notice. Then, caught in the middle, Diana Wynyard makes for one of the more convincing renditions I’ve seen of a woman battling desperately against total emotional meltdown. It’s a rare pleasure to encounter a film of this vintage in which all of the really important characters are portrayed with such skill and finesse, and it’s a pity that Gaslight itself is even rarer these days.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact