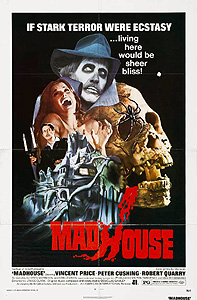

Madhouse / The Revenge of Dr. Death / The Madhouse of Dr. Fear / Deathday (1974) **

Madhouse / The Revenge of Dr. Death / The Madhouse of Dr. Fear / Deathday (1974) **

Sometimes, a very minor movie, little-seen and forgotten by almost everyone, proves unexpectedly illuminating. 1974 was a landmark year in the history of horror cinemaó not as big as 1973, probably, but plenty big enough. Most significantly for our present purposes, it was the year of Black Christmas and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, which between them marked the conception of the 80ís-model slasher movie. (Sometimes genres have a long gestation period, and this one was longer than most.) The slashers brought together a bunch of disparate genre lineages: body-count murder mysteries, the Colorful Killer and House Full of Crazies schools of spooky house movie, 60ís psycho-horror, the European giallo and Krimi traditions, the envelope-pushing gore innovations of David Friedman and Herschell Gordon Lewis, the gimmick-murder thrillers descended from Doctor X and The Mystery of the Wax Museum. Thereís always more than one possible way to combine a given set of influences, however, and thatís where Madhouse takes on a level of interest greatly disproportionate to its significance in the overall scheme of things (which is basically limited to its being the final horror film from Amicus Productions, made in partnership with American International Pictures). Madhouse assembles all the aforementioned elements, yet it is conspicuously not a slasher movie in the full sense of the term. The missing piece is anything resembling the mature slasher plot structure, in which the cast is steadily winnowed until only a protagonist or two remains to face down the killer. And equally noteworthy, Madhouseís eschewal of that structure (which, after all, was already in wide use among Continental European fright films) seems directly tied to its having something that slasher movies wouldnít make use of until A Nightmare on Elm Street accidentally found itself possessed of one a decade lateró an old-fashioned, 30ís-style horror star.

In fact, Madhouse has two of thoseó or possibly three, depending on how you score Robert Quarry. Vincent Price plays Paul Toombes, an actor best known for the long series of films in which he played the seemingly indestructible Dr. Death. Peter Cushing, meanwhile, plays Herbert Flay, Toombesís longtime friend and partner, who co-created Dr. Death and wrote most of the screenplays for his exploits. As for Quarry (whose shakier claim to horror star status rests on films like Count Yorga, Vampire and Deathmaster), heís a sleazy producer by the name of Oliver Quayle. When we meet this bunch, itís ďsome years agoĒ (to quote the scene-setting caption), and Toombes is throwing a studio party to celebrate the release of his latest picture. He also has a major announcement to make. In the very near future, Paul Toombes is getting married to Ellen Mason (Julie Crosthwaite), who was Dr. Deathís featured victim in the movie that just came out. The news comes as some annoyance to Faye Carstairs (Adrienne Corri, from Corridors of Blood and A Study in Terror), another former costar who would have liked to receive the promotion that Ellen is getting. Quayle, evidently a friend of hers, thinks maybe that can still be arranged. At the very least, he knows something that heís pretty sure would torpedo Paulís current wedding plans, and heís shameless enough to reveal that knowledge just for the hell of it. Oliver and Ellen are old acquaintances, too, you see. She made a few movies for him, as a matter of fact, back when he was just getting started as a smut-peddler. Given the timeframe here, Iím sure those films were innocuous enough, but Toombes loses his shit just the same when Quayle tells him, planting the idea in his head that at this very moment, in some skanky 42nd Street flea pit, fifteen rank-smelling guys could be ogling his fiancee with their peckers in their hands. The fight that ensues between Paul and Ellen is utterly vicious and humiliatingly public. What, then, should we make of it when somebody wearing a close approximation of Paulís Dr. Death costume lets himself into Ellenís dressing room shortly thereafter, and decapitates her? Donít bother asking Paul. He fell into a stress-induced blackout after calling off the nuptials, and by the time he comes out of it and goes to make his apologies to Ellen, sheís already dead. Toombes has no memory of the past half-hour or so, but heís honest enough with himself to recognize how this looks. Heís the first one to jump to suspecting him of the crime.

Evidently thereís no evidence firm enough to convince a grand jury, though, because instead of going to trial, Toombes goes to a mental hospital to be treated for a nervous breakdown. Upon his release in ďthe present day,Ē Paul finds himself attracting far more attention than he wants. There are reporters, of course, and the paparazzi, but even Herbert Flayís overtures to his old friend are less than entirely welcome under the circumstances. Flay has fallen on hard times, and Toombes soon receives a letter pleading with him to come back to England to support Herbert on a new venture. Thereís a TV show in the works, for which Flay is on call to head up the writing staff, based on his biggest hit from back in the day. That, of course, would be the Dr. Death franchiseó which unsurprisingly has rather negative associations for Toombes these days. Paul still isnít convinced that he didnít murder Ellen in some kind of fugue state, and he identifies Dr. Death with whatever part of his psyche could be capable of such deeds. He fears that to portray Dr. Death again would be to risk bringing that aspect of himself to the surface, so if it were anyone but Herbert asking, the answer would be a firm, flat no. But because it is Flay asking, Paul agrees at least to sail over and give the project a serious look.

On the crossing, Toombes has a late-night run-in with accomplished star-fucker and aspiring starlet Elizabeth Peters (Linda Hayden, from Letís Get Laid and The Blood on Satanís Claw). He doesnít know it yet, but sheís going to keep causing him trouble long after he succeeds in rousting her from his cabin. Much more to Paulís liking is Julia Wilson (Natasha Pyne), his liaison from the television studio, who meets him at dockside and chases away the press. Julia also informs him of the very advantageous living arrangements sheís made on his behalf. Flay has volunteered to take him on as a houseguest for the duration of the shoot. Thatís just the thing for a recluse like Paul, because Herbertís mansion is way out in the country and easily big enough to afford guests all the privacy they could ask for. As for the TV show itself, itís a done deal just as soon as Toombes gives his assent, with plenty of funding and broadcasters already in the bag. There is one bit of bad news, though. The producer for the Dr. Death show? Heís none other than that bastard, Oliver Quayle.

We all see where this is going, of course. Sooner or later, somebody is going to start dressing up like Dr. Death and killing people whom Toombes has reason to dislike, via methods drawn from Paulís old movies. The question is, is it really Paul, or is someone trying to gaslight him into framing himself? And if it is Paul, is the homicidal madness intrinsic to his personality as he fears, or is someone manipulating him into doing it? Suspicion on some level falls at once on Herbert Flay, because the first of the new Dr. Death slayings comes after Flay has Toombes watch one of his old movies to get back into the spirit of things, and Paul falls into what looks like a genuine hypnotic trance during a mesmerism scene. The victim is Elizabeth Peters, who picks exactly the wrong time to come prowling around Herbertís mansion in search of the One that Got Away. Subsequent victims are personnel from the TV show whom Paul resents for their insufficient professionalism. The police get involved, personified by Inspector Harper (John Garrie), but once again canít find any evidence that will stick to the obvious suspect. Soon, however, weíre made to rethink things a little, because somebody sabotages a stunt at the TV studio with the plain intention of killing Toombes himself. Meanwhile, Elizabethís parents (Ellis Dayle and Catherine Willmer, the latter of The Devils) come around, seeking not justice for their daughter, but blackmail to replace the revenue stream that the girlís stardom was supposed to provide them. Then things turn super-weird on the home front, as Paul discovers a hideously disfigured and completely insane Faye Carstairs living in the basement of the mansion amid a pack of venomous tarantulas. Eventually, Toombes has an altercation of his own with Dr. Death, resulting in what looks at first like an ending straight out of The Pit and the Pendulum. That isnít actually the end, however, and the real conclusion vaults right over the genre fence with an intrusion of the supernatural that, so far as Iíve seen, would not be matched in its disruptive freakishness until The Black Room in the following decade.

Thereís something important about Madhouse that Iím not sure how to account for. From the perspective of the present day, Dr. Death seems an unremarkable sort of character. Heís Freddy Kruger, Michael Myers, Jason Voorheesó the maniac you come back to again and again to see how heís going to exterminate the forgettable nominal protagonists this time. In 1974, though, there wasnít really any such thing as that yet. There were horror franchises, of course, and there were movies about gimmick killers, but to the best of my knowledge, no gimmick killer had ever been popular enough to hold down a franchise of his own. To arrive at a real-world analogue for Madhouseís Dr. Death series before the 1980ís, youíd have to pretend that The Mad Magician, The Abominable Dr. Phibes, Dr. Phibes Rises Again, Theater of Blood, and Madhouse itself had all been sequels to House of Wax, and that Vincent Price had portrayed the same character in all six films. Or at any rate, thatís what youíd have to do to arrive at a Dr. Death analogue in American or British horror movies. There are, however, a few interesting parallels in foreign cinema: Fantomas, Dr. Mabuse, and most of all Coffin Joe. Or alternately, we might look for precedent among chapterplay villains. Itís not the same thing as a franchise, to be sure, but people who turned out to see what the Crimson Ghost was up to every Saturday afternoon for three months could potentially form a similar kind of character attachment to that posited for Dr. Death fans here. And thereís always the wild-card effect that comes with Madhouse having been adapted from a novel. Iíve never read Angus Hallís Devilday, so I donít know how faithful an adaptation weíre talking about. But I can easily imagine a situation in which a pulp writer who wasnít a fan of horror films might misattribute to them some of the patterns of horror literature, which had been heavily dependent on series characters of all kinds since at least the 1920ís. Whatever the derivation, though, the makers of Madhouse unwittingly foretold the shape of things to comeó which ironically makes the movies-within-the-movie more modern than the movie itself.

Apart from the aforementioned areas of interest to paleontologists of the slasher film, Madhouse doesnít have much going for it. Peter Cushing seems tired, Vincent Price seems bored, and Robert Quarry doesnít have nearly enough to do. Price would have come by his apparent boredom honestly, too, since heíd already made five gimmick-murder flicks before thisó including one every year since 1971ó and all but Dr. Phibes Rises Again were significantly better than this one. The mystery of Dr. Deathís identity is too easy to solve, not least because the killer so obviously has to be one of the three name actors. I suspect thatís part of the reason why the horror star and the slasher formula never mixed well until the slashers abandoned all pretense of being concerned with whodunit. After all, what sense is there in putting a guy like Vincent Price or Peter Cushing in your movie, and then casting him as an uninvolved bystander? Madhouse foolishly tries to look like itís doing just that, which on top of being unconvincing results in Cushing and Quarry being counterproductively sidelined for far too much of the film. Furthermore, the motive behind the Dr. Death killings, when it comes to light, proves banal and lazy, and hardly seems worthy of all the effort put in by the villain. Madhouse becomes really enjoyable only when it and its sanity part companyó when charbroiled revenants start materializing out of movie screens or when Adrienne Corri is getting her Spider Baby on. I do rather like the Dr. Death costume, though, both the crude and crappy TV version and the more sophisticated interpretation worn by the killer.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact