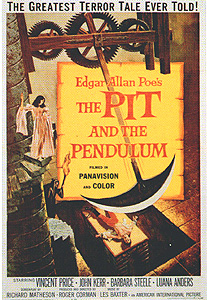

The Pit and the Pendulum (1961) ***½

The Pit and the Pendulum (1961) ***½

Roger Corman’s follow-up to The Fall of the House of Usher is, surprisingly enough, every bit as good as its predecessor, and may even represent an incremental improvement. I would, however, warn Poe purists to stay away from The Pit and the Pendulum. Richard Matheson’s script contains only the faintest hints of the exceptionally good story on which it claims to be based, resembling far more closely a complicated stew of all the most common recurring elements of Poe’s writing, at least until the final scene, when the Inquisition’s ingenious bisecting machine finally makes its appearance.

Indeed, on the basis of the first few scenes, a first-time viewer could be forgiven for believing he or she had turned on The Fall of the House of Usher by mistake. Like the earlier film, this one begins with the arrival of a lone man at the brooding, palatial home of a nobleman played by Vincent Price. In this case, the traveler is an Englishman named Francis Barnard (John Kerr). He has come to the coast of Spain to see his brother-in-law, Don Nicholas Medina (Price), in response to word of his sister’s untimely death. Barnard strongly suspects that Medina had a hand in Elizabeth’s demise, and his first impressions of Medina, Medina’s sister Catherine (Luana Anders, from Night Tide and Dementia 13), and household servant Maximillian (Patrick Westwood, of Destination Moonbase Alpha and “The Quatermass Experiment”) do nothing to assuage his fears. Medina positively radiates guilt, and his evasive explanation that Elizabeth was killed by “something in her blood” sounds none too convincing. Moreover, the morbid manner of her interment— like all the dead Medinas, she was walled up in the cellar of the castle— is both distinctly off-putting and rife with potential for concealing a murder. Catherine’s protests that her brother was in no way responsible for Elizabeth’s death would seem to be of little exculpating value, either, because by her own admission, she came to live with Don Nicholas only after his wife was already dead.

Matters only deteriorate when Nicholas’s physician, Dr. Charles Leon (Antony Carbone, from A Bucket of Blood and The Last Woman on Earth), arrives. Dr. Leon lets it slip out that there is more to the story of Elizabeth’s death than Medina has let on, and Barnard goes back on the warpath with renewed vigor. Eventually, Medina agrees to tell the whole story, despite warnings from both Leon and Catherine that to do so will endanger his frail health. The baron leads Barnard down into a locked room in the cellar, the door to which they had already passed on the way to Elizabeth’s tomb, and invites his guest to have a look around. The room is a torture chamber— a torture chamber with decades worth of dust collected on it, to be sure, but a torture chamber nevertheless. Needless to say, this doesn’t exactly do wonders for Barnard’s confidence in Medina, especially after the don tells him that this is where his sister died.

The truth is more innocent than Barnard’s imaginings, but only very slightly. The grim setup belonged to Medina’s father, Sebastian, one of the most feared and hated inquisitors in that ghastly institution’s long and bloody history. All his life, Nicholas has felt himself and his house cursed by the evil deeds his father committed in this hidden chamber, and he is quite certain that the castle’s palpable atmosphere of spiritual corruption was ultimately to blame for Elizabeth’s death. Not long after she moved into the castle, she began to decline, and to develop a morbid fascination with Sebastian Medina’s chamber of horrors. Nicholas would frequently find her hanging out, brooding among the racks and wheels and whipping posts, and she would often sleepwalk to the chamber on those rare nights when she did, in fact, sleep. Finally, Elizabeth simply disappeared. Medina searched all over the castle for her, but it wasn’t until he thought to look in the dungeon that Elizabeth turned up— locked, apparently dead, in Daddy’s old iron maiden.

But there’s more. When Catherine gets Barnard alone with her, she lets him in on a nasty little secret from her brother’s childhood. One day, little Nicky got curious about just what his father did down in that locked room in the basement. While he was snooping around, trying to figure out what hideous purpose all the wicked-looking devices served, his father suddenly came into the chamber, accompanied by his mother and his uncle Bartolome. Nicholas hid behind one of the machines, and thus got a front-row seat to the spectacle of his father accusing his mother of cheating on him with Bartolome, braining Bartolome with a red-hot iron, and then torturing his mother almost to death. His mother was then walled up in the family crypt to die from thirst, starvation, or her injuries— whichever got to her first. It’s that last part that has had the worst and most lasting effect on Nicholas. Indeed, he has half convinced himself that he accidentally had Elizabeth buried prematurely, despite Dr. Leon’s assurances that she came out of the iron maiden quite dead.

The spooky stuff begins the night after Francis hears the two stories about his host’s past. Maria the maid (Lynette Bernay, from I Bury the Living and The Saga of the Viking Women and Their Voyage to the Waters of the Great Sea Serpent) hears Elizabeth whispering to her, someone or something completely trashes the dead woman’s old bedroom, and Medina really starts to lose it, having concluded that Elizabeth’s angry spirit is haunting him in revenge for having been buried alive. After a couple days of this, Medina resolves to open Elizabeth’s tomb in the hope of discovering once and for all if his fears have any foundation. With the help of Barnard and Leon, Medina sets to work chopping through the wall that conceals his wife’s coffin. Many exhausting hours later, Medina pries open the casket, and gazes upon Elizabeth’s withered corpse, which, though badly decayed, is unmistakably the body of someone who died while trying to claw her way free. Nicholas isn’t in very good psychological shape after that.

Barnard doesn’t believe in ghosts, though, so to his way of thinking, this grim revelation raises more questions than it answers. You see, nobody but Dr. Leon, Catherine, and Medina himself even knew that Nicholas thought Elizabeth might have been entombed alive. And yet— if we exclude vengeful ghosts from consideration— the circumstances clearly point to somebody trying to use the don’s guilty obsession as a weapon against him, perhaps in order to get his or her hands on the obviously considerable Medina fortune. Dr. Leon, too, has begun thinking along these lines, and it is his opinion that one of the servants is the culprit. But as we shall soon see, it is nothing so simple as that, for Nicholas begins hearing Elizabeth’s voice, too. When he follows her lilting calls down into the network of secret passages that riddle the thick walls of his castle, ultimately winding up in his father’s old dungeon, he is finally confronted with Elizabeth herself (Barbara Steele, from Black Sunday and The Crimson Cult). And as if that weren’t enough to snap the poor man’s sanity right in two, the appearance of Dr. Leon in the torture chamber with her, and his subsequent admission that the two of them faked Elizabeth’s death in order to facilitate an affair they’d been having behind Medina’s back for years most certainly is.

And that’s where the two conspirators make their fatal mistake. Thus far, this movie has been conspicuously lacking in two departments: pits and pendulums. Both of those shortcomings are about to be rectified, much to the disadvantage of Leon and Elizabeth. If the adulterers wanted to drive Nicholas mad, they have most assuredly gotten their wish now, but the precise form that madness takes spells trouble for them both, and for Barnard, too. Confronted with a scene so similar in its setup to that which he witnessed as a boy in the very same chamber, Nicholas quite literally forgets himself. He plunges headlong into the memory that has tormented him so over the years, and begins to relive it, but with one crucial difference— this time, Nicholas plays the scene out from his father’s point of view. Locking Elizabeth up in the same iron maiden that supposedly ended her life the last time, Medina then turns his attention to Leon. The doctor falls to his death in the deep pit that occupies much of the darkened room behind the torture chamber, but before the delusional Medina has a chance to process that information, Barnard rushes into the room, drawn by all the commotion. The unfortunate Englishman is incorporated into the don’s revenge fantasy, taking the place of the recently slain Leon, and it is Francis who ends up strapped to the pedestal in the center of pit in the next room, while the razor-sharp mechanized blade descends slowly toward him. The way I figure it, he’s got three chances: Catherine, Maximillian, and Maria. Let’s just hope they heard all the racket attendant upon Medina’s freak-out, too.

It was with The Pit and the Pendulum that the Corman-Matheson team first seriously came up against the toughest obstacle to filming Edgar Allan Poe— his stories are too short and too concerned with inner monologues of madness, obsession, and fear to translate easily into a feature-length movie. “The Pit and the Pendulum” presents an even bigger challenge than most in this respect, because it has but a single character worthy of the name, and nearly all the action of the story takes place entirely within that character’s mind. Stretching the story out to an hour and a half and adapting it to the requirements of a visual medium like film could be done only by converting its plot into a single, climactic vignette, and that is exactly what Matheson did with his screenplay here. Truth be told, the character of Poe’s writing already suggests such treatment— it has always seemed to me as though he bothered to write only the endings of his stories— and in that light, The Pit and the Pendulum proves far more faithful to its source than it might at first appear. This in itself is something of a triumph. The movie is also helped by a much better cast than had worked on the seminal The Fall of the House of Usher, and the one holdover in the cast, Price himself, puts in a much stronger performance. Then again, the film is weakened by its rather excessive similarity to its predecessor on the one hand, and its shameful underutilization of Barbara Steele on the other. Even so, it remains a worthy continuation of the AIP Poe cycle, and it’s easy to see why Corman and his bosses would feel it worth their while to make so many more such movies.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact