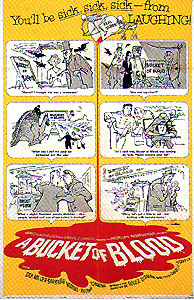

A Bucket of Blood (1959) ***

A Bucket of Blood (1959) ***

A Bucket of Blood was the first of a trio of horror comedies that arguably marked the climax of the first stage of Roger Corman’s directorial career— the phase in which the main consideration driving his work appeared to be “Just how fast can we get this picture in the can, anyway?” Corman spent just five days shooting A Bucket of Blood, his fastest turnaround time to date in 1959. (He would top that record by better than half with The Little Shop of Horrors the following year, while the third entry in the triptych, Creature from the Haunted Sea, was shot in a comparatively leisurely six days.) The surprising thing about this movie is that the ridiculously cramped shooting schedule had little apparent effect on its quality. Its sights are set relatively low, but A Bucket of Blood is quite effective for what it is.

What it is, as I’m sure you’re eager to read, is a sort of super-low-budget beatnik variation on The Mystery of the Wax Museum. Walter Paisley (Dick Miller, from The Terror and Not of This Earth) is the busboy for the Yellow Door coffeehouse, a popular beatnik hangout owned by Leonard de Santis (Antony Carbone, of The Last Woman on Earth and Creature from the Haunted Sea). Paisley is— and this is putting it kindly— a shlub. Yet, surrounded each and every workday by the out-crowd’s in-crowd, Paisley wants nothing more than to be accepted into the mutual adulation society of poets, artists, and writers whose tables he clears for a living. He seems particularly struck by the words of poet Maxwell Brock (The Masque of the Red Death’s Julian Burton), who contends that only the creative are truly alive. Of course we also shouldn’t discount the influence of an artist named Carla (Barboura Morris, from Atlas and The Wasp Woman), who is both the only person in the Yellow Door scene to treat Paisley decently, and the pretty girl for whose attentions the hapless busboy futilely pines.

All of that baggage is chasing itself around in circles in Paisley’s mind one night when he comes home from work to the tiny flophouse apartment he rents from Mrs. Surchart (Myrtle Vail, from The Little Shop of Horrors). The whole business has finally got Walter so worked up that he’s bought himself a big glob of sculptor’s clay, to which he sets himself the moment he walks in the door. His efforts hit a snag, however, in that he possesses not one iota of artistic talent. Then, right when his frustration is at its peak, he hears the anguished mewing of Mrs. Surchart’s cat, Frankie, which has somehow managed to get itself trapped inside the wall of his apartment. Figuring the place is already such a dump that a little more damage here or there won’t much matter, Paisley attempts to free Frankie by cutting a hole in the shamefully thin drywall with a kitchen knife. He is no more successful in this endeavor than he was at sculpting the human face, however, for instead of releasing the cat, he impales it on the knife. But the next morning, while Walter is trying to figure out how he’s going to tell the landlady that he killed her pet, he has a brainstorm. If he were to coat Frankie’s carcass in clay, he could pass it off as a sculpture of his own making, sparing himself the ire of Mrs. Surchart and giving himself an inroad to the Yellow Door art scene all in one go.

Dead Cat, as Paisley entitles his “sculpture,” is a roaring success. Carla loves it (she’s particularly impressed with Walter’s grasp of anatomy), and even Leonard de Santis grudgingly concedes that the piece has merit. De Santis agrees to display Dead Cat in the Yellow Door, and to split the proceeds from its sale with Walter, 50-50. The fawning of the scenesters that evening is even more lavish. Maxwell Brock hails Paisley as an undiscovered genius, and a woman named Naolia (Jhean Burton) is so overwhelmed that she offers to go home with Walter that very night. That’s a bit more than our hero is prepared for, though, so instead, Naolia gives him a small vial as repayment for the “gas” she experienced while looking at Dead Cat. That, as it happens, is where events begin to spiral out of Paisley’s control. He doesn’t know it, but the vial Naolia gave him contains a substantial quantity of heroin, and while he doesn’t know this either, Yellow Door regulars Lou Raby (Jennifer’s Bert Convy) and Art Lacroix (Ed Nelson, from The Brain Eaters and Night of the Blood Beast) are undercover cops who have been trying for weeks to get to the head of the drug racket that supplies the coffeehouse’s clientele. Lou trails Walter home, and places him under arrest for possession of narcotics. Raby’s had better ideas in the course of his career. His prey panics at the prospect of jail, and before Lou knows what’s happening, Paisley whacks him on the head with the edge of a heavy aluminum skillet. Needless to say, Murdered Man soon joins Dead Cat in Walter’s newly acquired artistic portfolio.

So it’s awfully inconvenient for the despised busboy-turned-coddled artiste that Leonard accidentally knocks Dead Cat from its perch on the counter, causing some of the clay to chip free. At first, de Santis thinks of nothing beyond how much fun he’s going to have exposing Paisley as a fraud, but the picture changes once he hears about Murdered Man. When he and Carla go to Walter’s apartment to see the new work for themselves, it’s all de Santis can do to keep his dinner where it belongs. In fact, Leonard is inclined to call the cops on Walter, but then he has a little talk with a wealthy art collector (Bruno VeSota, of The Giant Leeches and The Wild World of Batwoman), who offers to buy Dead Cat for the stupendous sum of $500. Leonard’s resolve wilts a bit at that.

Meanwhile, there’s still one person in the Yellow Door scene who isn’t impressed with Walter Paisley. That one person is a particularly obnoxious snob named Alice (Judy Bamber, of Monstrosity and Dragstrip Girl), who pays her bills by hiring herself out as a nude model for $25 an hour. Alice’s taunting makes Walter so mad that he decides to employ her himself, with exactly the result you’d predict. The trouble with this scenario is that Paisley has now put himself in the position of having to kill people in order to maintain his reputation and all that comes with it. It was one thing to create sculptures as a means of concealing crimes he committed essentially by accident, but it’s something else altogether to rely on premeditated murder to keep himself in the public eye. And let us not forget about Art Lacroix, who has got to be wondering by now just what became of his partner in the Yellow Door stakeout. More serious yet, consider what will surely happen in the event that Walter has misread Carla, overestimating her feelings for him now that he’s an “artist” too…

Given that Dick Miller is best known as a character actor, it’s fascinating to see what he does with a leading role. This is an odd leading role that we’re talking about, to be sure, but it still means Miller gets to carry an entire movie instead of showing up for a few minutes to add color to a scene or two here and there. Truth be told, he does a fairly impressive job of it. In his hands, Walter Paisley comes across as both authentically likeable and authentically pitiable, both necessary traits for a sympathetic lead in a comedy about a serial killer. As a dim-witted but sensitive guy who happens also to be a complete loser, he is believable enough to serve the movie’s purposes whether it’s asking us to accept him bungling his way into murder in the first place or sustaining his killing spree in order to maintain the acceptance that was denied him until it began. And those who have hitherto seen Miller only in the rather whimsical bit parts that became his stock in trade will have a real surprise coming during the scene between Walter and Carla that finally pushes Paisley over the edge.

A Bucket of Blood is also notable for the difference between its comedic stance and that of the later The Little Shop of Horrors and Creature from the Haunted Sea. While the latter two movies play primarily as farces, satire is the name of the game in A Bucket of Blood. Corman and screenwriter Charles Griffith logged quite a few hours in beatnik coffeehouses before getting to work in earnest, and all that homework pays off handsomely. Though I obviously have no firsthand knowledge of the subculture this movie lampoons, the attitudes and personalities of the characters have exact cognates in other subcultures with which I am directly familiar; update the lingo and change the music, and the Yellow Door would be all but indistinguishable from a modern indie-rock club. That this rather unflattering portrait of an insular and self-impressed art scene should ring so true today across a gulf of four decades and at least as many cycles of youth-culture reinvention shows just how much attention Corman and Griffith paid on their scouting missions. However accurate or inaccurate their rendering of the details, they captured something essential about the way scenes like this function, and did a fair job of skewering it. Just don’t look too hard for the bucket of the title— there’s a saucepan of blood visible in the background during one scene, but of buckets, this movie is entirely destitute.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact