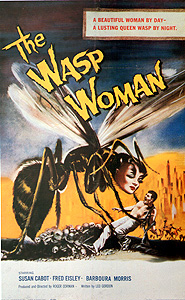

The Wasp Woman/The Bee Girl/Insect Woman (1959) ***

The Wasp Woman/The Bee Girl/Insect Woman (1959) ***

Even the cheapest, clunkiest monster movie can have depth and layers to it in the right hands. And despite his well-earned reputation as an unrepentant trash-peddler, Roger Corman has repeatedly shown himself capable of pulling unexpected insights and surprisingly sophisticated themes out of even the stupidest material. The Wasp Woman, the last of Corman’s 50’s monster flicks (most audiences didn’t get to see it until early in 1960), would certainly seem to offer little promise for those who expect more from a horror or science-fiction movie than a shitty monster suit and a woman in peril, but Corman and screenwriter Leo Gordon somehow managed to turn it into something startlingly serious and mature. This is not to say that it is without a shitty monster suit or a woman in peril, however. Both of those things are very much in evidence.

But the movie doesn’t start out with either one of them, beginning instead with the obligatory nutball scientist, and I figure that’s where we should start too. The scientist’s name is Dr. Eric Zinthrop (Michael Mark, from Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe and Attack of the Puppet People), and he’s an entomologist working for a company that does most of its business selling honey. Zinthrop’s studies have nothing to do with honey production, though. Instead, the company is paying him to do research on royal jelly, the special food with which bee colonies feed the larvae that are destined to grow up into queens. The supposed health and beauty benefits of royal jelly were just starting to be touted in the late 1950’s, and Zinthrop’s employers are interested in developing methods of getting the bees to produce it in sufficiently large quantities to be profitably harvested for use in cosmetic and health-food products. That being the case, it’s easy to understand why the scientist’s direct boss is so irritated with him at the moment. Rather than doing what the company is paying him for, Zinthrop has gone off on his own tangent, experimenting with the royal jelly of wasps in the hope of transforming it into a sort of elixir of youth. (Dr. Science wishes him lots of luck— there isn’t one known wasp species on Earth that produces anything analogous to the royal jelly of honeybees.) The company suit— who always took Zinthrop for a crackpot anyway— gives him the sack the moment he learns the true meaning of that $1000 invoice for “miscellaneous” the scientist sent the home office last week.

Back in Los Angeles, there’s another company with rather bigger worries than $1000 worth of the inexplicable on a researcher’s expense account. Starlin Enterprises, the cosmetics company owned and operated by former glamour model Janice Starlin (Susan Cabot, from War of the Satellites and The Saga of the Viking Women and Their Voyage to the Waters of the Great Sea Serpent), has seen its sales decline fully 14% during the preceding quarter, and Starlin herself wants to know how her cabinet of underlings account for the downturn. Most of the men in the conference room remain uncomfortably silent, but young hotshot Bill Lane (Anthony— or “Fred,” as he’s identified here— Eisley, of Dracula vs. Frankenstein and The Navy vs. the Night Monsters) is not afraid to speak up, or to place the responsibility squarely on the shoulders of his boss either. The way Lane sees it, the decline in the company’s fortunes coincided directly with Starlin’s decision to step aside as public face of the firm. For eighteen years, it’s been Starlin the consumers have seen on every billboard, magazine ad, and TV commercial, and when she made the decision back in February to bring in a group of new spokesmodels to take her place, the public began to lose faith in Starlin Enterprises. Starlin, simultaneously flattered and chagrined, agrees with Hall’s analysis, but doesn’t see what can really be done about it— as she says herself, “Not even Janice Starlin can be a glamour girl forever.”

Enter Eric Zinthrop. He’s been a busy man since being fired from the honey company, and he has achieved truly stunning success with his vespid royal jelly formula. When he showed his old boss the results of his project that fateful day, all he could do was arrest the aging process; now he has the power to reverse it as well. Zinthrop’s letter to Starlin offering the commercial license on his formula arrives later the same day as the meeting at which Hall told her what he thought had gone wrong with the company. I’m sure you can imagine how the eccentric scientist’s promises of restored youth sound to Starlin, so it will come as no surprise that she signs him on as a sort of special consultant reporting to no one but her, empowered to get whatever he needs in order to bring his research to fruition. But beyond its psychological resonance for Starlin, Zinthrop’s project is also just plain old good business— if it works, Starlin Enterprises will have a product on their hands with which none of their competitors could possibly hope to compete. There is a price to be paid for the unlimited support Starlin offers, however. Zinthorp must accept his new boss as his first human research subject, and he must begin experimenting upon her immediately after he has his lab at the company headquarters up and running.

Starlin keeps the project secret at first. She reasonably concludes that her subordinates— especially in-house scientist Arthur Cooper (William Roerick, from Not of This Earth and God Told Me To)— would think her mad even to consider spending thousands of dollars of company money on a quest for the Fountain of Youth, and Zinthrop would rather his work remain under wraps until it produces real results, anyway. But as it turns out, the secrecy itself catches the attention of Cooper, Hall, and even Starlin’s personal secretary, Mary Dennison (Barboura Morris, from The Dunwich Horror and A Bucket of Blood). Opinions are more or less evenly divided throughout the company over whether Zinthrop is a talented con artist or a totally sincere quack, but either way, Cooper and company have no doubt that he’s trouble. All three begin doing what they can to check up on Zinthrop whenever Janice has her back turned.

The funny thing is, the real trouble comes from Janice Starlin herself. She wants results and she wants them now— even if that means sneaking into Zinthrop’s lab after closing time to inject herself with higher doses of the wasp jelly drug than the scientist considers safe. The higher doses have the desired effect, and soon Janice looks nearly as young as she was when she began the company almost two decades before. Unfortunately, they also have the unforeseen side-effect of turning Starlin into a were-wasp! What’s more, Starlin has become so attached to her restored youth that she seems to feel no qualms about the murders she commits whenever she transforms. And wouldn’t you know it, Zinthrop goes and gets himself run over by a car right after he figures out how much danger everyone at Starlin Enterprises is in, but before he has a chance to tell anyone about it.

Not that this would ever happen, mind you, but if I somehow were to find myself teaching an introductory women’s studies course at a state university somewhere, I would definitely have all my students watch The Wasp Woman. The fascinating thing about this movie is the way it turns the usual mad scientist plot completely inside out. Rather than having the scientist abduct and victimize the female lead, forcing her to become the subject of his insane research against her will, The Wasp Woman makes the human guinea pig herself the instigator of the experiment that turns her into a monster. And in a manner that verges on brilliance, Corman and company make it entirely comprehensible that she would do such a thing, and allow her to remain a basically sympathetic character while they’re at it. Janice Starlin is a woman in a predicament which few men ever face. Her rise to wealth, power, and prestige may have stemmed primarily from her intelligence, decisiveness, and business savvy, but it was her beauty that got her the opportunity in the first place, and she has traded on her looks every step of her way to the top. Beauty doesn’t last, however (I mean, have you seen Lina Romay lately?), and those characteristically feminine forms of success that hinge on it are therefore inherently precarious and generally fleeting. Starling is not old, and she certainly isn’t unattractive, but she is no longer the head-turner she used to be, and that worries her so much that she is willing to do literally anything to forestall any further decline. More importantly, her reaction in the face of looming maturity seems, for someone in her position, to be the natural and indeed even rational one. If you make your living from your looks and an opportunity to maintain those looks comes along— even if it comes at a very high price— you’d almost have to be crazy to turn it down.

Now the obvious way to proceed from there would have been to have a slimy and unscrupulous scientist latch onto Starlin’s insecurities and exploit them for his own gain. That’s not what happens here, though. Zinthrop’s professional ethics are a bit questionable, but he isn’t out to take advantage of anybody. Janice makes it a condition of his deal with her that the scientist use her in his experiments, and at every stage, she pushes him to go beyond what he considers safe and responsible. Indeed, when she can’t get what she wants from him, Starlin goes behind Zinthrop’s back and undoes all his efforts to ensure that prudence and caution carry the day. There’s still a form of gender inequity at work here, but it’s a far subtler and more complex variety than usually comes into play in the movies— particularly in the relatively cut-and-dried gender environment of the 1950’s. What leads Janice Starlin to her dreadful fate is not direct masculine exploitation, but rather her own conscious decision to exploit herself as a commodified sex-object. Having built an eighteen-year career as, essentially, a professional hot chick, she now feels as though her very identity is threatened by her advancing age. When Zinthrop offers her what looks like a miraculous chance to change the rules in the middle of the game, she jumps at it with hardly a thought for the possible negative consequences.

There is a pitfall inherent in framing the story this way, but between Corman, Gordon, and Susan Cabot, the movie sidesteps it most adroitly. It would be easy to turn Janice into an out-and-out villain, making her ruthless and self-involved, but to do so would rob The Wasp Woman of much of its power as drive-in social criticism. Make Starlin a callous, calculating harridan, and the film would play out as a simplistic, conservative cautionary tale about what happens when a woman tries to step outside of her prescribed place. But because of Cabot’s extremely astute, extremely sympathetic performance, together with that boardroom scene early on which establishes the impossibility of her situation, we end up taking Starlin’s side from the very beginning, and the thrust of the movie turns around 180 degrees. Yes, Starlin turns into a monster through the backfiring of a desperate bid to hold onto her power and position in what was, in 1959, unquestionably a male domain. But The Wasp Woman makes it very clear that it isn’t Starlin in the wrong, but the system itself. You leave it saying to yourself, “Yeah, but what the hell else was she supposed to do?” If it weren’t for the generally shoddy production values and that pitiful, pitiful monster suit, I’m quite certain this would have become one of the most respected horror films of its era.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact