The Saga of the Viking Women and Their Voyage to the Waters of the Great Sea Serpent / Viking Women and the Sea Serpent / Viking Women (1957) **½

The Saga of the Viking Women and Their Voyage to the Waters of the Great Sea Serpent / Viking Women and the Sea Serpent / Viking Women (1957) **½

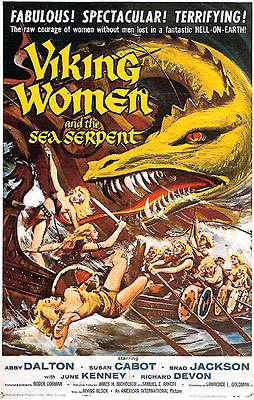

The Saga of the Viking Women and Their Voyage to the Waters of the Great Sea Serpent was a huge, strange departure for both American International Pictures and director Roger Corman, which makes it all the more remarkable that I can see no obvious reason for either party to have made it. The idea originated with Irving Block, a special effects artist associated with Jack Rabin. Block and Rabin commissioned a script from recidivist television wordsmith Lawrence L. Goldman (fresh from Kronos, and looking to continue his foray into feature screenwriting), and then put together a pitch package of concept art to shop around among Hollywood’s independent producers. Corman was one of those they approached, and although he thought the project was too risky for his own resources, he arranged for Block and Rabin to meet with Samuel Z. Arkoff and James H. Nicholson at AIP. Arkoff and Nicholson liked what they saw, committed about $80,000 (rather on the high side for them in those days, if you can believe that), and gave Corman the job of directing the picture. Rabin and Block, meanwhile, went off with about a quarter of the budget to create the maelstrom and sea monster footage for the film’s two biggest set pieces.

Nothing terribly unusual about any of that— it was approximately the way AIP always dealt with outside operators like Herman Cohen or Bert I. Gordon. The compelling question is why a Viking movie, as early as 1957? None of the startlingly numerous European Viking flicks had been made yet, let alone worked their way across the Atlantic to American theater and television screens. Hell, even The Vikings, the Kirk Douglas vehicle that provoked the European fad for movies about Norse sea-raiders, was almost a year in the future when Block and Rabin first got to work. Nor, for that matter, would the earliest of Ray Harryhausen’s seafaring fantasias for Columbia Pictures be released until 1958. The closest thing I can find to a plausibly timely impetus for the AIP project is the revival of interest in swashbuckling adventure films generally in the 1950’s— but none of those pictures had the fantastical elements that formed The Saga of the Viking Women and Their Voyage to the Waters of the Great Sea Serpent’s core. This was, in other words, a movie without apparent precedent, and without apparent links to any larger zeitgeist.

To be sure, AIP in those days was as likely to innovate as to imitate. After all, 1957 was also the year the company launched its famous and hugely profitable cycle of teen monster movies, and the following decade would bring the even more transformative Edgar Allan Poe and beach party cycles. But one of the keys to Arkoff and Nicholson’s success was that they and the people working for them knew how to innovate on the cheap. The Saga of the Viking Women was by AIP standards an expensive production when it was green-lit, and perhaps more importantly, it was also an expansive one. Arkoff, Nicholson, and Corman alike would be biting off more than they’d ever attempted to chew before, and on no firmer basis than a bunch of nifty concept paintings and a verbal summation of a script that none of them would be in a position to read until shooting was ready to begin. It’s all the stranger, then, that on the distribution side, The Saga of the Viking Women was to be treated no differently than any other AIP production. Far from receiving any kind of prestige release, it went out on the bottom half of a double bill with The Astounding She-Monster, with no greater distinction than that the pairing would serve as the first AIP two-fer of 1958. It’s a real puzzle all around, and I have yet to find anything that looks like a solution.

Three years ago, Vedric (Bradford Jackson), the chief of a Viking tribe called the Stonjold, set sail with all his men of fighting age save one to win through plunder the living that his inhospitable land had ceased to provide by more peaceful means. They’ve never been heard from since. Now the women of the tribe are fiercely debating the question of whether or not to go out after them. The “pro” party is led by Desir (Abby Dalton, later— much later, in fact— of CyberTracker and Prank), to whom Vedric was married or betrothed or handfasted, or whatever it is the Stonjold do in that direction. Her reasons for wanting to hit the high seas in search of the missing men should be fairly self-explanatory. The “anti” faction follows Dagda (Lynnette Bernay, from I Bury the Living and The Pit and the Pendulum). She contends that the loss of the Stonjold men is a punishment from the gods, although she never quite gets around to explaining what for. Regardless, if it was the gods’ will that Vedric and his forces fail to return from their raiding, then it stands to reason that Thor and company won’t like the women going out to search for them, either. The factions are evenly matched, so the decisive vote is cast by Enger, the tribal priestess (Susan Cabot, from War of the Satellites and The Wasp Woman). To the surprise of practically everybody, Enger votes to ship out. The more Dagda thinks about it, though, the better sense it makes that the priestess, who has always coveted Desir’s man, would want to find him just as badly as her rival.

The voyage of the Viking women gets off to a rocky start when their hastily constructed drakenskiff throws its rudder while launching, forcing the inexperienced sailors to fall back on the older and less efficient technology of the steering oar. (The loss of the rudder was a real accident, by the way. Corman realized early on, though, that the ten-day shooting schedule authorized by Arkoff and Nicholson was inadequate as it was, and that nothing would be gained by beaching the ship, resetting the rudder, and filming retakes of the launch until they got one in which the vessel remained in one piece.) Then on the first night out, Thyra (Betsy Jones-Moreland, of Creature from the Haunted Sea and The Last Woman on Earth) discovers a stowaway in the form of Ottar (Jonathan Haze, from Blood Bath and Monster from the Ocean Floor), the runty lad whom Vedric had deemed not worth bringing along three years ago, and whom the women similarly meant to leave behind now. It seems strange at first that Desir, Enger, and the rest are so nonchalant about getting stuck with him anyway, but their change of heart is explained when it comes to light that Ottar, unlike any of the Stonjold females, has been to sea before. He may not be as strong even as Desir’s younger sister, Asmild (June Kenney, from Attack of the Puppet People and Earth vs. the Spider), but he knows how to hold a course, how to rig a sail, and maybe even how to navigate.

The first sign that the women are on the right track is an ominous one. Floating in the waves far out from home, Desir spies a wooden object that turns out to be part of a drakenskiff’s mast. Desir has a narrow escape from a shark while investigating her find, but that isn’t half as serious a peril as the one that abruptly looms up soon thereafter. A serpentine creature a hundred feet long or more surfaces off the starboard quarter, and proceeds to swim rapidly in vast circles, generating a powerful whirlpool. Ottar has heard tell of this Monster of the Vortex, but always dismissed it as just another of the tall tales so beloved by seafaring folk. Knowing what the thing is doesn’t exactly help, though, now that it evidently has its heart set on sinking the Stonjold’s ship. Worse yet, it seems the sea serpent has the power to call down thunderstorms, for the sky above its maelstrom becomes as savagely agitated as the sea, until a bolt of lightning streaks down to strike the mast of the ship. The sail ignites, the ship breaks apart, and those who survive the wreck will no doubt have a few new ideas about what might have befallen Vedric and the men.

The voyagers who live to wash up on an unfamiliar shore number seven: Desir, Asmild, Enger, Dagda, Thyra, Ottar, and a woman called Sanda (Sally Todd, from Frankenstein’s Daughter and The Unearthly), whose only distinguishing characteristics are that she’s exceptionally blonde and exceptionally pretty even among her present company. Almost immediately after regaining consciousness, the castaways are rounded up and marched off across the rocky, arid hills overlooking the shore by a party of swarthy, ugly horsemen under the command of a slightly less brutish character by the name of Zarko (Michael Forrest, of Beast from Haunted Cave and Atlas). Their destination is the fortress of Zarko’s lord, the Great Stark (Richard Devon, from The Blood of Dracula and The Undead), king of the Grimolt people, and the reception the Vikings receive from him is difficult to parse. On the one hand, Stark avers that despite the rough handling they got from Zarko, the castaways are to regard themselves as guests rather than captives. But at the same time, the Grimolt king is perfectly up-front about considering it the Stonjold women’s destiny to become mates for him and his warriors, whether they want to or not. The Grimolt worship the Monster of the Vortex as one of their chief gods, you see, and Stark reckons any lives spared by the sea serpent his to dispose of as he wills.

Stark is just in the process of explaining that when his twerp son, Senya (Jay Slater), flounces in to ask what’s keeping him; everyone is ready for the day’s big boar hunt, and His Majesty is holding up the works. The king then emphasizes his hospitable side by inviting the Vikings to join in— assuming, of course, that they aren’t all too weary from their fight with the monster, the ensuing shipwreck, and their forced march from beach to castle. Ottar, with a small man’s unerring instinct for the ways of bullies, immediately accepts on behalf of all the Stonjold. After all, it wouldn’t do to show the slightest hint of weakness in front of the Grimolt, and participating in the hunt might even afford Ottar the opportunity to slip away for a bit of reconnoitering. In fact, though, the main event of the hunt occurs when Senya wanders off from the pack. Thrown from his horse and missing his cast with his spear, the prince comes very close to being killed by the boar, but his bacon is saved by Desir, who brings down the pig in mid-charge. Far from being grateful, however, Senya is incensed that a mere girl has excelled him in what his people regard as the manly arts. The Grimolt, evidently, don’t go in for Norse notions of sexual equality, and so Desir has brought disgrace on the prince by saving his life. Luckily for Senya, Desir is less hung up on honor than he is, and since there were no other witnesses to the kill, she sees no reason not to let Stark and the others believe that Senya hurled the fatal spear instead. For perhaps the first time in Senya’s life, his father publicly expresses pride in him, and for a while it looks as though the Vikings have made themselves a highly placed friend.

The prince pushes Desir’s indulgence one step too far at the celebratory feast that night, however. Hoping to impress his dad a second time, Senya challenges Viking leader to an arm-wrestling match, and although he wins the first trial, the second goes sharply against him. Stark, appalled, puts a stop to the whole business at once, and from that moment on, the Stonjold women are treated not as prospective wives, but as slaves. They’ve got company in that, as it happens. When Ottar takes violent exception to the change in his people’s status, Stark brings all the Vikings in his custody to see the mines where his less privileged captives are forced to labor. There are four Norsemen on the current chain gang— and would you believe that one of them is Vedric? Sure you would. Indeed, no fewer than three of the enslaved miners are the long-missing lovers of somebody in Desir’s crew. (The fourth man, Jarl [Gary Conway, of How to Make a Monster and Black Gunn], probably went to sea with Vedric, too, but he’s by far the youngest of the male prisoners, and may not have been deemed marriageable three years earlier.) Technically, then, the women’s mission is now a success, albeit on rather different terms from those they envisioned when they set out. Those new terms naturally give rise to a corresponding new mission: to spring Vedric and the others from the mine, and to escape from the land of the Grimolt. Obviously that places the Stonjold captives in opposition to Stark, Senya, Zarko, and a whole castle’s worth of ursiform bruisers, to say nothing of that sea serpent they’ll have to slip past in the event that they overcome their human foes. But what nobody except maybe Dagda expects is that Enger is prepared to turn against her own people in order to claim Vedric for herself.

It’s hard to believe that The Saga of the Viking Women and Their Voyage to the Waters of the Great Sea Serpent is less than 66 minutes long— not because it drags, but because Lawrence Goldman and Roger Corman between them have squeezed so much stuff into that hour and change. The film has a boar hunt; a banquet scene incorporating a notionally sexy dance routine, two bouts of surprisingly dramatic arm wrestling, and a brawl; two major (for 1957 AIP values of “major”) battles; two layers of romantic intrigue, as Enger puts the moves on Stark in order to get her hands on Vedric; two human sacrifices; a test of strength between the gods of the Grimolt and those of the Stonjold; and of the greatest significance for most likely viewers, two fights at sea against a giant monster in the center of a whirlpool! Inevitably, 80 grand couldn’t buy terribly impressive versions of any of that, but the sheer moxie of this movie is breathtaking. And the efficiency with which The Saga of the Viking Women zips through its immense surfeit of plot and action leaves me even more ill-disposed than I was to begin with toward the modern presumption that no tale of this size and complexity can possibly be told in less than two and a half hours.

That’s especially true because The Saga of the Viking Women and Their Voyage to the Waters of the Great Sea Serpent never takes its breathless pace as an excuse to skimp on characterization or relationships. A lightly sketched odd-couple romance develops between Ottar and Thyra, the butchest and brawniest of the Stonjold women, giving her an unexpected chance to demonstrate that she’s the most nurturing of the bunch as well. Ottar has a second mini-arc, too, in the form of his running enmity with Zarko. The Grimolt captain somehow always seems to be Ottar’s opponent in any general melee, and kicks his ass every time— until the fight in the surf during the second phase of the climactic escape sequence, when Ottar deftly exploits the buffeting of the waves to wear down his stronger, heavier foe. Desir and Asmild show a believably sisterly affection for each other in all their interactions, a bit of onscreen chemistry that may have had some behind-the-scenes boost; Roger Corman was under the impression that Abby Dalton and June Kenney were sisters in real life, although I’ve found no corroboration of that from other sources. Richard Devon and Jay Slater have a compelling interpersonal dynamic, too, as Stark and Senya. The latter is plainly unfit for the role thrust upon him as the former’s son and presumptive successor, but nobody understands that better than Senya himself. Everything we ever see the prince do— including even his rather farcical death— is part of some hapless, foredoomed attempt to please or to impress his father, yet the one time he succeeds is due to dishonestly borrowing glory that rightly belongs to Desir. Stark, meanwhile, is disappointed to the point of disgust with his weak, ineffectual heir, but his actions following Senya’s demise prove that deep down, he loved the lad even so. Especially considering that these are the villains we’re talking about, it’s impressive to see so much effort and creativity devoted to portraying them as complicated human beings. The meatiest and most memorable role, though, is that of Enger, who starts off as a rival to the main heroine and transitions into out-and-out villainy, only to end by undergoing one of the most satisfying heel-face turns in all of 50’s junk cinema. Here again the material limitations of the production limit the achievements of the finished product in turn, but this movie is doing a lot more with its characters than initially meets the eye.

The last point I want to address concerns the occasion for Enger’s final turn into the light. Remember that she’s the priestess of the Stonjold, making her at least in theory the Earthly agent of the Aesir. The turning point of the film, both in terms of the overall plot and for her personally, comes when Stark has finally had enough of his Viking slaves’ persistent unruliness, and decrees that Desir and Vedric be burned alive in sacrifice to the unnamed Grimolt storm god. Despite all her evil machinations thus far, Enger cannot bear to see two of her own people sacrificed to a foreign deity, and she calls upon Thor to unleash his storm-related power to put a stop to the ritual. At that moment, a powerful thunderstorm blows up out of nowhere, and the torrential rain extinguishes the fires burning around Desir’s and Vedric’s feet. It’s right out of a Cecil B. DeMille biblical epic, which is a pretty unexpected turn for the story to take merely on a tonal level. But when you factor in which god is doing the intervening here, the moment becomes truly astonishing. I quite simply cannot recall seeing the like of it in any other film of this era. I’m not sure which blindsided me harder: seeing Norse religion treated as valid in a cheapjack AIP programmer from 1957, or finding enough material for a five-page review in one that’s barely more than an hour long.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact