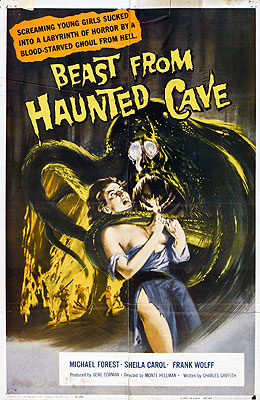

Beast from Haunted Cave (1959) **½

Beast from Haunted Cave (1959) **½

Filmgroup is something of a forgotten chapter in the Roger Corman story, which is a bit weird considering how ubiquitous the company’s products became with the rise of public domain home video labels in the mid-2000’s. The Wasp Woman, The Little Shop of Horrors, Creature from the Haunted Sea, Battle Beyond the Sun— those were all Filmgroup titles. To some extent, I imagine the issue is simply that Filmgroup’s brief lifespan overlapped with the most fruitful phase of Corman’s much longer and better-studied relationship with American International Pictures, while the vibe of the typical Filmgroup production was basically “just like AIP, but even cheaper.” I know I misremember Filmgroup flicks as AIP releases all the time.

In any case, the reason for Filmgroup’s existence was sort of a second-order replay of how Corman got into the creative side of the movie business in the first place. Just as his gig as freelance screenwriter and unpaid production assistant on the 1953 Allied Artists picture, Highway Dragnet, got Corman interested in producing films of his own, four years or so of watching Samuel Z. Arkoff and James H. Nicholson sell his movies gave him the itch to run his own studio, with its own distribution network. His younger brother, Gene, happened to know lots of theater owners, so Roger brought him onboard as a junior partner to handle that side of the business, while he concentrated on developing and/or acquiring the movies themselves. Both brothers would act as producers on individual Filmgroup projects, and Roger ended up directing several of them as well. The company launched in 1959, with a slate of five films— Beast from Haunted Cave among them— most of which wouldn’t see wide release until the following year.

As it happened, though, Filmgroup was never truly successful, and the venture might be best understood as the venue where Corman made all the mistakes that taught him how not to drive New World Pictures straight into a ditch ten years later. More than anything, Filmgroup ran afoul of the old adage that in order to make money, one has to be willing to spend money first. Roger strove to hold the company’s budgets down to $50,000 per picture or less (preferably a lot less), and its shooting schedules to under a week. Filmgroup productions made in Hollywood were often filmed in a frantic scramble on some recently completed larger movie’s sets, during the final few days before the removalists came to dismantle them. Even that was a bit of a luxury, though, because wherever possible, the elder Corman preferred to send miniscule casts and skeleton crews on location to parts of the country where the entertainment industry’s unions either held no sway, or were governed by the lower rates dictated by their less hardnosed Chicago chapters. And those expeditions never yielded just one film, so long as there was any possibility of squeezing in two before the flight back home to LA. Even copyright registration was treated as a needless extra expense, which is how it eventually came to pass that every budget DVD company on Earth offers its own crummy edition of The Terror and Dementia 13. In addition to pissing off just about everyone who ever had the dubious fortune to work on a Filmgroup movie, all that over-the-top penny-pinching resulted in products so conspicuously cheapjack and threadbare that few exhibitors wanted them, and few cinemagoers could be persuaded to take a chance on them wherever they did play. The Corman brothers were too ruthless to lose money (with the solitary, instructive exception of The Intruder), but Filmgroup’s total annual profits were routinely on the order of a few thousand dollars. That wasn’t viable even in the early 1960’s. Unsurprisingly, Gene quit early in 1963 to take a job at 20th Century Fox, after which Roger shut down the distribution side of Filmgroup, and started releasing the firm’s output through AIP (thereby blurring the distinction between the two companies even further). He pulled the plug altogether four years later, with Voyage to the Planet of Prehistoric Women being the final movie to carry the Filmgroup logo.

But now let’s rewind back to 1959, and to Beast from Haunted Cave. In a lot of ways, this movie was a harbinger of everything that would make Filmgroup Filmgroup. It was produced in tandem with an unworkably cheap World War II action programmer called Ski Troop Attack, on location in South Dakota’s Black Hills— which is to say, on the territory of those Chicago-based showbiz unions I mentioned. Although Gene was the producer of record for Beast from Haunted Cave, the concepts animating both films were Roger’s. His marching orders to screenwriter Charles Griffith were to rewrite his old script for Naked Paradise (a noir-in-the-tropics cheapie that the elder Corman had directed on the same trip to Hawaii that spawned She-Gods of Shark Reef) around a gold mine in the mountains, trading the hurricane for a blizzard and adding a monster to make the recycling a tad less obvious. While Roger himself took the helm on Ski Troop Attack, the task of directing Beast from Haunted Cave fell to a first-timer by the name of Monte Hellman, whom the Cormans knew through his then-wife, Barboura Morris. (Like so many people who got their first break in the movies from Roger Corman, Hellman went on to be rather a big deal, even if his time in the spotlight was shorter than, say, Peter Bogdanovich’s or Francis Ford Copolla’s.) And of course the trip became legendary for the wheeling and dealing Roger did to secure favorable concessions left and right from local businesses, including an astounding $1.00-per-night-per-room bargain with the hotel where the cast and crew were booked, two to a room. But most of all, Beast from Haunted Cave foreshadowed what was to come from Filmgroup in the sense that there’s a surprisingly clever, edgy, and psychologically astute movie concealed within its junky exterior.

Alexander Ward (Frank Wolff, of Atlas and The Lickerish Quartet) robs banks. He’s very good at it, too— enough to support a globe-trotting lifestyle appropriate to the successful international businessman he habitually pretends to be while staking out prospective targets. Ward’s current team consists of two henchmen by the names of Byron Smith (Wally Campo, from The Little Shop of Horrors and The Strangler) and Marty Jones (Creature from the Haunted Sea’s Richard Sinatra), together with his hard-drinking girlfriend, Gypsy Boulet (Sheila Carol— or Sheila Noonan, if you prefer— from A Bucket of Blood and The Incredible Petrified World). Their current caper brings them to the South Dakota mining town of Deadwood, in order to steal gold bars from the disproportionately well-stocked vaults of the local bank.

Ward’s scheme relies on a double diversion. Posing in his usual guise, he hires ski instructor Gil Jackson (Mark Forest, of King Kong Lives and The Saga of the Viking Women and Their Voyage to the Waters of the Great Sea Serpent) to lead him and his companions on a cross-country skiing excursion through the Black Hills, setting up both their alibi and their getaway. Jackson himself will most likely need to be eliminated once the criminals are far enough from town to slip away successfully, but omelets and eggs, right? On the night before the heist, Marty is to plant a time bomb inside the mine nearest to the lodge where they’re staying, while Gypsy seduces Gil. Jackson will then have reason to welcome the change in plans when Alex, Marty, and Byron plead a slow start in waking up, and encourage him and Gypsy to begin the trek without them. That will leave the men free to hit the bank unobserved and unopposed after the bomb detonates in the mine, drawing every cop, fireman, paramedic, and able-bodied, civic-minded resident in town to the site of the disaster. By the time Ward and his henchmen catch up with Gypsy and Gil on the trail, they’ll have two gold bars apiece stashed in their rucksacks, and Jackson— easy enough to dispose of under the cover of forest, snow, and the darkness of night— will be all that stands between the thieves and a clean and profitable escape.

There are three things Ward hasn’t figured on, however. First, a blizzard descends on Deadwood right around nightfall, forcing the criminals to seek shelter at Jackson’s cabin. Not only will that delay Ward’s planned getaway, but it also means another witness to silence, in the form of Gil’s Lakota housekeeper, Small Dove (Kaye Jennings, another future member of the Creature from the Haunted Sea cast). Second (and don’t tell me you didn’t see this coming), Gypsy winds up falling for Gil for real. Some sort of jealous explosion from Alex is thus almost guaranteed, to say nothing of what Gypsy might do now once she realizes that Ward intends to kill Jackson and Small Dove to prevent them from talking. But the third unforeseen complication is by far the most serious. Marty breaks into the mine in company with a pretty barmaid called Natalie (Linné Ahlstrand, of Living Venus), on the pretext that doing so will give them someplace both private and secret to violate the Hays Code. The ruckus they create goes unheard by human ears, but it attracts a predatory, nocturnal creature evidently released by the miners’ delving from some unsuspected subterranean ecosystem. The arachnoid monster seizes Natalie and wraps her up for later feeding, and although Marty manages both to get away and to plant the bomb like he was supposed to, the spider-thing evidently gets a good enough look (or listen, or sniff) at him to track him down later. It’s going to want to do that, too, because it’s intelligent enough to connect Marty’s intrusion to the destruction of its lair when the bomb goes off in the morning. Worse, it’s evidently less inconvenienced by blizzards than humans are, for while Ward and the gang hole up in Jackson’s cabin, it forges ahead to set up shop in an ill-reputed cave which its prey will have to pass by if they continue on their current route. Beyond its obvious value as an ambuscade, that cave is advantageously situated to serve as a base from which the creature can attack the cabin in the event that it grows impatient waiting for Marty and the others to come to it.

It’s easy to see why Monte Hellman had such a bright future ahead of him. The material conditions under which he made Beast from Haunted Cave were quite simply absurd, and yet he turned in a movie noticeably better than most of those his boss had directed during his first couple years at AIP. First of all, Hellman got good value for the off-the-beaten-path shooting location, creating a vivid sense of the setting: the town itself, with its somnolent streets, shabby accommodations, and barely extant nightlife; the tourist-luring ski slopes, rising to prominence in the local economy as the mines begin to play out; most of all, the unforgiving bleakness of a Black Hills winter. Similarly, the sequences shot underground to represent both the mine where Marty plants his bomb and the titular Haunted Cave are atmospheric in a way that one seldom sees in cheap monster movies from this era. But naturally my favorite triumph over Beast from Haunted Cave’s material limitations concerns the creature itself. Hellman found exactly the right approach for this thing, showing enough to convey how far it differs from the customary man in a rubber suit (somewhat like its counterparts in Attack of the Crab Monsters, it’s more like a man built into the core of an ungainly puppet), but keeping it sufficiently obscured by shadows and odd camera angles to prevent the viewer from ever forming more than a disquietingly vague impression of its size or form.

Mind you, Hellman had a lot of help from Charles Griffith. Although the real motive for recycling the Naked Paradise script was quick turnaround time, doing so fortuitously gave Griffith a chance to hone his prior plotting and characterization in a way that the original picture’s typically rushed production schedule hadn’t permitted. Furthermore, because Beast from Haunted Cave was rewritten from a script that fell far outside the horror genre, its non-horror aspects end up being unusually effective in their own right. After all, the caper plot originally had to be strong enough to support a whole movie all by itself, without any help from vengeful spider-monsters. Griffith chose a smart means of introducing the creature, too. By bringing it in before the heist, he establishes it as a looming threat that none of Ward’s carefully laid plans can have taken into consideration. The monster also factors into the expected fragmentation of the gang even before it starts hunting them across the Black Hills, because of the conditions under which the criminals initially encounter it. First, there are reports of a mad cougar in the area when Ward and company arrive in Deadwood, suggesting a mundane alternative explanation for the spider-thing’s activities. Second, Marty is the only one who sees it the first time it strikes, and he is understandably so flustered as to be barely coherent when he returns to the lodge to report on his mission to sabotage the mine. Put the two together, and you get a completely reasonable opening for Ward to conclude that Marty is cracking up, and may have to be cut loose before all is said and done. And naturally that prospect will loom ever larger as the creature closes in, even once its actual existence becomes obvious to everyone snowed in at Jackson’s cabin.

Rather to my surprise, however, my favorite thing about Beast from Haunted Cave belongs almost solely to the noir side of the film. Sheila Carol’s Gypsy Boulet is a just-about-perfect intersection of performance and character writing. She’s almost totally corrupt, and yet sadly nostalgic for a time when she wasn’t. If you asked her straight out, I’m sure she would tell you that she was a sucker for playing by the rules before she took up with Ward, and that the life of a bank-robber’s moll has given her everything she ever wanted— but her virtually non-stop angry boozing tells a different story altogether. And now along comes Gil Jackson, whom she’s just supposed to fuck over the way she’s no doubt fucked over half a hundred other credulous, horny shlubs in her time, and suddenly she sees that there’s a way out of all this if she has the nerve to take it. It’s an extremely meaty role for a film on this level, and Carol dives right into it for all she’s worth. Her performance completely blindsided me, although I suppose I shouldn’t have taken my principal other experience with her as indicative of her true abilities. After all, who could possibly do their best work wandering aimlessly around a hole in the ground for 70-odd minutes, under the direction of Jerry Warren?

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact