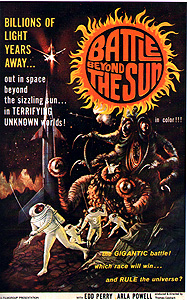

Battle Beyond the Sun (1963) **

Battle Beyond the Sun (1963) **

To be perfectly honest, I’ve always found Roger Corman more interesting as a producer than as a director. That isn’t to say that I’m not fond of the directorial work he did under the auspices of American International Pictures— those quirky and frequently proto-feministic monster movies from the studio’s formative years, the Poe films of the early 60’s, the guardedly sympathetic cinematic examinations of the hippy and biker countercultures from the latter half of that decade— but directing was something that Corman had sort of blundered into, and it absorbed a relatively modest fraction of his extraordinary lengthy filmmaking career. His fifteen years as a director constitute an impressive run to be sure, but that’s nothing beside the 56 years he’s spent producing in some capacity. So eager though I am to plug the remaining holes in my coverage of Corman’s years behind the bullhorn, I’d rather focus my share of the B-Masters Cabal’s unaccountably belated tribute to B-cinema’s most titanic titan on Corman’s wheeling, dealing, and making shit happen.

There are few better illustrations of how far outside the “rules” Corman was willing to stray in the name of putting something interesting up onto theater screens than the string of deals he made on an excursion behind the Iron Curtain in 1962. The official motive for the trip was the Pula Film Festival in Zagreb, to which Corman had somehow secured an invitation. At the festival, he was introduced to a Yugoslavian producer with whom he rapidly negotiated an arrangement to import Francis Ford Coppola and some actors from his just-completed The Young Racers to make a quickie espionage thriller as an American-Yugoslavian co-production. That film mutated into Blood Bath over the next four years, which is a story unto itself. More to the present point, Corman bracketed his stay in Zagreb with visits to Kiev and Moscow, and on the latter stop, he met with representatives of Mosfilm and Sovexportfilm, the Soviet state-run production and international distribution firms. Nothing came of Mosfilm’s proposed offer of a year-long Moscow-based filmmaking contract, but the Sovexportfilm meeting led to Corman going home with the rights to several Russian-made science fiction and fantasy movies. Altered to varying extents, these movies would trickle into American release under the Filmgroup and American International Pictures banners, either theatrically or on television, over the next five years, with the work of adapting them for US audiences entrusted to whichever young protégé Corman was then grooming for a solo directorial career of his own. Battle Beyond the Sun, the second of these “Corman Cut-and-Pastes” to reach Western viewers, was one of Coppola’s contributions to the process, cut down and rearranged from the gorgeous but staid The Heavens Call.

The Heavens Call was in a sense the most challenging of Corman’s Sovexportfilm acquisitions to rework, for its disaster movie-style plot explicitly hinges upon incompetent, glory-hungry Americans getting themselves into trouble and being bailed out by heroic, self-sacrificing Russians. Furthermore, Coppola’s instructions were to shoot no new footage beyond a few minutes of monster sequences intended to spice up the third act. There would be no inserts with washed-up Hollywood stars (like those that later converted Planet of Storms into Voyage to the Prehistoric Planet and Voyage to the Planet of Prehistoric Women), and wholesale reshoots like those that would transform A Dream Comes True into Queen of Blood were completely out of the question. Consequently, Battle Beyond the Sun makes do with a clunky opening voiceover explaining that in 1997— an unspecified length of time after a ruinous nuclear war— the world has reorganized itself into a pair of globe-spanning mega-states known as North Hemis and South Hemis. The leaders of these new polities have apparently learned nothing from the fate of their predecessors, however, for North Hemis and South Hemis are engaged in a cold war of their own, complete with a space race remarkably similar to that which once preoccupied the vanished United States of America and Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.

South Hemis currently has the lead in the latter contest, with Dr. Gordon (Ivan Pereverzev), the genius top man of its space agency, preparing to launch the rocketship Mercury on the first manned mission to Mars. Even the Mercury can’t make a trip of that duration after battling the Earth’s gravity and atmospheric friction, however, so Gordon’s plan has the great vessel embarking instead from the orbiting space port overseen by his military counterpart, Commander Daniels (Viktor Dobrovolsky). Gordon will command the Mercury mission himself, but he’s no space pilot. That task will fall instead to Paul Clinton (V. Chernyak), with Craig Matthews (Aleksandr Shvorin)— who happens to be dating Gordon’s daughter, Nancy (Taisiya Litvinenko)— waiting in the wings as a backup in case something should happen to incapacitate Clinton between now and zero hour. And yes, that is a hint of future developments. This is all to be done under the utmost secrecy, though, because the leaders of South Hemis are concerned that it would be a blow to Southern prestige were the mission to fail. With that in mind, Gordon’s labors will be revealed to the public only if and when they have come to fruition.

On the day before the Mercury’s scheduled launch, the space port receives unexpected visitors in the form of two astronauts from North Hemis, whose vessel, the Typhoon, is in need of repairs. The Northerners are mission commander Captain Torrence (Gurgen Tonunts) and civilian scientist Dr. Martin (Konstantin Bartashevich). The reversal of the military and civilian roles among the Typhoon crew relative to the situation aboard the Mercury might tell us a thing or two about how things are done in North Hemis. Regardless of the rivalry between the two powers, Daniels permits the Typhoon to land, and he and Gordon receive Torrence and Martin as honored guests. Indeed, since they’re all space explorers here, the Southerners even reveal the plan for tomorrow’s Mars launch. That comes as an unwelcome surprise to Torrence, for he and Martin are also bound for Mars in much the same furtive fashion. At the earliest opportunity, Torrence radios home to inform his superiors that they’ve been caught with their pants down. The general above him orders strict adherence to the mission plan even so, but Torrence’s pride will permit no such thing. He falsely informs Martin that their schedule has been moved forward, and the Typhoon blasts off for Mars that very night— in so big a hurry that Paul Clinton, standing watch on the launch pad, is wounded by the ignition, and with the vital repairs that had grounded the rocket in the first place only partially made.

Needless to say, nothing good comes of Torrence’s haste. The influence of the solar wind upon the Typhoon’s still-glitchy guidance system diverts the rocket onto a course straight for the sun, and only Dr. Gordon’s humanitarian instincts save Torrence and Martin from a swift and fiery death. When Matthews intercepts the Typhoon’s distress call midway through the voyage to Mars the next day, Gordon orders the main mission postponed for the sake of rescuing the otherwise doomed Typhoon crew. The diversion puts Mars temporarily out of reach, and the Mercury is forced to set down on the asteroid Angkor, which has fallen into a convenient if distant orbit around the Red Planet. From there, it should be a simple matter of waiting for South Hemis mission control to send up an unmanned supply rocket to top off the Mercury’s fuel tanks, but there are two unforeseen complications. First, a rash of sunspot activity sets up a field of electromagnetic interference that jams the communication uplink between the unmanned rocket and the Mercury’s guidance system; Paul Clinton, recovered now from his injuries, will have to mount a manned resupply mission instead. Secondly, and of much greater importance, Angkor is not the lifeless rock it appears to be from the surface. The asteroid is riddled with caverns, and within them dwell the fearsome Penisaurus and its natural enemy, the Vulvadon! Clinton is going to have an exciting walk from one rocket’s landing site to the other’s, let me tell you. No, the sad hand-puppet monsters aren’t really called the Penisaurus and the Vulvadon, but they sure as hell ought to be. And in case you were wondering, the duel between them that Clinton has the foul luck to wander through is the closest thing we’ll ever see to the promised Battle Beyond the Sun.

Battle Beyond the Sun is markedly less successful at repurposing an ostensibly unreleasable Soviet movie than Voyage to the Prehistoric Planet, partly because The Heavens Call was originally so much better than Planet of Storms, and partly because Coppola did such an amateurish job of dubbing and recutting it. At 64 minutes, Battle Beyond the Sun is drastically shorter than its Russian source, yet it manages to be rather a bore even despite the addition of its jaw-dropping climactic monster battle. A lot of the trouble is that Coppola startlingly displays an almost Jerry Warren-like disregard for the pacing and flow of the original footage, together with a tendency to repeat sequences in obviously inappropriate ways. He cavalierly uses images of the Typhoon in scenes that supposedly feature the Mercury, reruns clips that struck him as particularly useful both forward and backward, and even replays entire scenes with different overdubbed dialogue. Presumably he figured that nobody would notice, but I assure you that you will. The other major defect relates directly to the great mass of footage that Coppola chopped out in a wholly unsuccessful effort to accelerate The Heavens Call’s admittedly glacial pace. Although Coppola (and Corman even more so) might have seen nothing but talk, talk, and more talk in the excised material, what really gets lost is the Russian film’s unusual and commendable effort to invest its characters with depth and nuance. Contrary to most of what you’ll hear from people who have only read about The Heavens Call, that movie was as fair-minded and even-handed as Gosfilm would ever have allowed it to be, and with the exception of the cartoonishly villainous Verst (as Torrence was called the first time around), it was careful to portray everyone as reasonably credible people, with clear individual motives and personalities. Battle Beyond the Sun, in contrast, serves up as unidimensional a bunch of ciphers as you’ll find in any threadbare sci-fi programmer.

What Coppola couldn’t screw up, and what accounts for the bulk of Battle Beyond the Sun’s entertainment value, is the magnificence and spectacle that motivated Corman to buy The Heavens Call in the first place. It was among the most beautiful science fiction movies of the 1950’s in Mikhail Karzhukov’s hands, and until the laughable monsters show up, it’s among the most beautiful science fiction movies of the 1960’s in Coppola’s. Given the enormous difficulty that continues to confront Westerners wishing to see Karzhukov’s version, Battle Beyond the Sun retains significant residual worth as the most readily available presentation of this material. Even shorn of virtually all subtext, of all political perspective, of practically everything that once made it interesting beyond the level of sheer eye-candy, this movie still offers a few muted hints of what Western sci-fi fans were missing out on during the 40 years when the United States and the Soviet Union were not on speaking terms. In fact, a couple of Soviet sci-fi’s less obvious characteristics stand out more prominently with the class ideology and great-power politics bleached out. Note, for example, how many women there are in Dr. Gordon’s space agency, and that not a single damn one of them is ever shown serving coffee to anybody. Note also that there are ugly people in Battle Beyond the Sun, cast in parts that are not defined by their ugliness, and that all characters, without exception, are played by actors of an age appropriate to their roles. I won’t go so far as to assert that such things make the Eastern Bloc’s sci-fi movies superior to our own, but it undeniably is instructive to see what the genre looks like divorced from Hollywood’s persistent neuroses about youth, beauty, and gender roles.

Finally, there’s one tiny little positive contribution that Coppola made in Battle Beyond the Sun, and it would be remiss of me to let it go unremarked— especially since everybody else seems to. Think for a moment about the geopolitical situation in this vision of a post-nuclear future. Ignore for now the indiscriminate employment of Anglo-Saxon names in Coppola’s dub, and observe that the heroes in this movie hail from South Hemis, while the bad guys, if such they may be called, are Northerners. Observe also that South Hemis is depicted as the more technologically advanced and politically progressive of the two mega-states. Now think about where most of the H-bombs would have landed in the nuclear war that reset the global political system. As I observed in my review of On the Beach, there wasn’t much south of the equator that NATO or the Warsaw Pact signatories would have considered worth nuking in the early 1960’s, so it makes all the sense in the world that the nations of the southern hemisphere would enjoy a leg up on their competitors to the north following a nuclear war that stopped short of exterminating the human race, either directly or via postwar fallout distribution. Again, it isn’t much, but it’s a sign that Coppola did at least a little bit of honest thinking when he devised his scenario for removing the real-world Cold War from Battle Beyond the Sun.

This review is part of a long-overdue B-Masters Cabal salute to the incomparable Roger Corman. Click the banner below to read my colleagues’ words of praise both heartfelt and damningly faint.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact