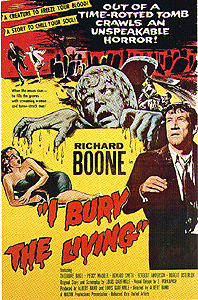

I Bury the Living (1958) ***

I Bury the Living (1958) ***

I’ve been itching for years to see I Bury the Living, ever since I first read this shorthand synopsis in Stephen King’s Danse Macabre:

Once upon a time there was a cemetery caretaker who discovered that if he put black pins into the vacant plots on his cemetery map, the people who owned those plots would die. But when he took out the black pins and put in white pins, do you know what happened? The movie turned into a big pile of shit! Wasn’t that funny? |

Now that’s a seduction, there— you know what I’m saying? And old Steve is right on the money, too. I Bury the Living does indeed turn into a big pile of shit once our hero gets it into his head to try the white pins, but up until then, it’s one of the coolest, most imaginative horror films of its decade.

The Krafts— owners of the Kraft’s department store chain— are in all probability the most prominent family in the smallish New England town of Milburn. Naturally they are phenomenally rich, but their status doesn’t derive from money alone. The family also maintains a number of philanthropic concerns, which the members of the department store’s five-man board of directors take turns managing on a yearly basis. One of these volunteer projects is the caretaker-ship of the Immortal Rest cemetery, and this year, that duty falls to the board’s newest member, Robert Kraft (The Last Dinosaur’s Richard Boone, who was also the voice of Smaug in The Hobbit), who took over the post vacated when his father died a couple of years ago. Kraft would just as soon have nothing to do with the place, but a family obligation is a family obligation, and besides, all he’ll really be responsible for is the paperwork. The hard stuff— maintaining the grounds, carving names on the headstones, digging the actual graves— is handled by a Scottish immigrant named Andy McKee (Dark Tower’s Theodore Bikel), who has held the job since before anybody can remember. Kraft wants to pension him off and replace him with a younger man, but McKee prefers to stay on. And since Kraft puts McKee in charge of finding his own replacement, it seems a safe bet that none will be forthcoming any time soon.

The little cottage that will serve as Kraft’s office when he’s performing his duties as caretaker is dominated by a gigantic wall-map of the cemetery, which positively bristles with black- and white-headed straight pins. As McKee explains, the pins enable the caretaker to see at a glance what the status of any individual plot in the graveyard is. Black pins indicate where someone is already buried; white pins signify that a plot has been purchased, but is currently empty. And speaking of people buying plots, an acquaintance of Kraft’s by the name of Stuart Drexel (Glen Vernon, from The Screaming Woman, who had a brief but conspicuous onscreen turn as the gilded boy in Bedlam) stops by Immortal Rest with his new wife, Elizabeth (Lynette Bernay, from The Pit and the Pendulum and The Saga of the Viking Women and Their Voyage to the Waters of the Great Sea Serpent), to claim one each for himself and his bride. But Kraft isn’t paying attention when he sticks pins in the map to designate the couple’s plots as spoken for, and he uses black pins rather than white to mark them. You’d have known that was significant even if I hadn’t quoted that passage from the King book, wouldn’t you?

The very next day, Robert learns that both of the Drexels are dead, killed in an auto wreck mere hours after he sold them their plots. And after the funeral, when he goes to the map to change their pins, he notices the black ones already stuck in the map, and realizes the mistake he made the preceding afternoon. It gives him an eerie feeling, as if he himself had marked the couple for death, but he understands that he’s not being rational even before he bounces the idea off his reporter friend, Jess Jessup (Herbert Anderson), who works for the Milburn Herald. In fact, the only person who seems to get the way Richard feels about that mix-up with the pins and the subsequent sudden deaths of the Drexels is Andy McKee, who still has enough of the superstitious Old World in him to be unnerved by the coincidence.

Kraft’s and McKee’s respective cases of the wiggins only intensify when it happens a second time. Again, a customer comes in to buy himself a plot, and again, Robert isn’t watching his hands when he picks up a pin with which to mark the transaction on his map. Kraft’s customer has a fatal heart attack that very night, and the caretaker just about loses it when he hears the news. This time, he goes to his fellow board-members with the story, and asks to be relieved of his duties at Immortal Rest. Naturally, none of his colleagues greet the tale of the killer map with anything but total incredulity, but Robert’s uncle George (Howard Smith) is at least perceptive enough to see how seriously the two incidents have affected him. George agrees to come with Robert to see the offending map, and when he does, he proposes a little experiment. All five members of the Kraft’s board of directors own plots at Immortal Rest; Robert will switch one of the men’s pins from white to black, and when the man so designated suffers no ill effects (as George is certain he won’t), then Robert will at last be free of this debilitating new obsession. George nominates Henry Trowbridge (Russ Bender, from War of the Colossal Beast and The Satan Bug) as the experimental subject, and Robert reluctantly changes his pin. I don’t think I need to tell you what news greets the Krafts when they report to work the next day.

Things escalate rapidly from there. The surviving members of the board are still not convinced, and they vote unanimously for Kraft to switch all of their pins the next time he goes to the cemetery. The theory seems to have been that three simultaneous deaths would be so unlikely a coincidence as to cross over into sheer impossibility, but all this newest trial produces is three more dead bodies. Then, when Kraft goes to homicide detective Lieutenant Clayborne (Robert Osterloh, who had previously played tiny parts in The Day the Earth Stood Still and Invasion of the Body Snatchers) with the story of the deadly map, the cop insists on yet another test of its supposed power. Kraft is just about at his wits’ end when the results of Clayborne’s test turn out the same as all the others, but a few minutes later, he has a sudden flash of clarity. Whatever malign synergy exists between him and the map gives him the power to kill with the black pins, right? Then shouldn’t the same force, when acting through the white pins, have the opposite effect? In a virtual fugue state, Kraft pulls the black pins from all the plots in which his victims (if we may call them that) lie buried, and inserts white pins in their places. Then he wisely barricades himself in the office cottage, surmising that anyone who climbs out of the graves he sent them to earlier might not be in the best of moods when they emerge. Don’t get your hopes up, though. Screenwriter Louis Garfinkle reaches down into the big trunk marked “Bait and Switch” at this point, and pulls out a real whopper.

Not since The Beast with Five Fingers had a horror film gone out on a more annoying note. The parallel between that movie and I Bury the Living is made even stronger by the fact that both pictures, up until their disastrous final reels, are among the finest that their eras have to offer. I Bury the Living comports itself in the same manner as the very best episodes of the original “Twilight Zone,” and begins with just the sort of off-kilter premise that made that show so memorable when it was at the top of its game. But unlike “The Twilight Zone,” I Bury the Living never takes a preachy or sentimental tone, even for a minute. Albert Band’s direction is exceptionally crisp for a 50’s film, with nearly as much drive and energy as the rest of United Artists’ 1958 lineup combined. The cast is strong in an understated way, and benefits from including nobody whom I particularly recognize— and wonder of wonders, the Cartoon Scotsman isn’t unendurably annoying. Finally, I Bury the Living is well served by a highly distinctive score which draws just the right amount of attention to itself. You’re always aware of it, and of its lack of meaningful similarity to any other horror movie music you can remember, but it never distracts you from the action unfolding above it. If only it weren’t for that stupid, stupid ending…

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact