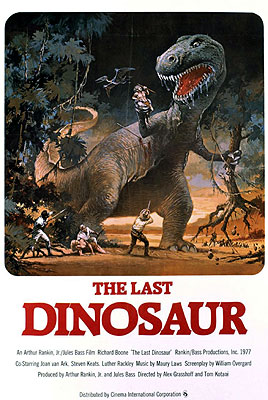

The Last Dinosaur / Kyokutei Tankensen Pora-Bora (1977) -***

The Last Dinosaur / Kyokutei Tankensen Pora-Bora (1977) -***

Although mainly an animation studio (including both traditional cel animation and a stop-motion variant which the company branded as “Animagic”), Rankin-Bass did dabble from time to time in flesh-and-blood filmmaking. And because the firm had always outsourced the hands-on production of its cartoons to Japanese companies, it made sense for them to seek similar partnerships for their live-action projects as well. Most famously, Rankin-Bass teamed up in 1967 with Toho to produce King Kong Escapes, an extremely loose adaptation of their contemporary “King Kong” Saturday-morning cartoon series. Fans of that movie will be pleased to learn that there’s more where it came from. Rankin-Bass don’t appear ever to have worked specifically with Toho again, but ten years after the Kong film, they entered into a new alliance with Tsuburaya Productions, the studio behind “Ultraman” and its spinoffs. For the uninitiated, that’s “Tsuburaya” as in Eiji Tsuburaya, Toho’s resident special effects sensei of the 50’s and 60’s. Eiji himself died in 1970, but the company he started toward the end of his long association with Toho remained a family concern, and was under the leadership of his younger son, Noboru, when Rankin-Bass came calling. Tsuburaya Productions, although hampered by the straitened circumstances of the Japanese movie industry in general during the 1970’s, continued to do pretty impressive work on absurdly low budgets and impossibly tight schedules, making them attractive partners for an American studio that sold most of its output directly to television. Their collaboration lasted from 1977 to 1980— long enough to yield three pictures, all of them involving rubber-suit monsters of the sort that Tsuburaya had specialized in since 1965. The films went straight to TV in the US, but played theatrically not only in Japan, but in several other overseas markets as well. The Last Dinosaur was the first out of the gate. It’s unmistakably cheap, and conceptually obsolescent in a lot of ways, but it’s also well worth watching due to a melding of Western and Japanese sensibilities so seamless as to be downright disorienting.

Petroleum baron Masten Thrust (Richard Boone, from Lizzie and I Bury the Living) is quite possibly the single wealthiest man in the world. Nevertheless, he… Hey, come on! Stop that! Just ’cause his name is Masten Thrust, that’s no reason to… Wait. No, you’re right. I can’t plausibly expect anyone not to laugh uncontrollably at a name like that. Go ahead and get it out of your systems. I’ll wait.

Better?

How about now?

Okay, anyway— Masten Thrust, owner and CEO of Thrust Industries…

Damn it!

Okay, how about now?

Right. So that guy, whose full name I won’t mention again lest you all descend helplessly into guffawing once more, has never attained anything like the happiness, contentment, or serenity that those less materially well-off than him might assume based on the size of his bank accounts or the obsequious bowing and scraping that greets him wherever he goes. He hasn’t even attained the happiness, contentment, or serenity that ought to accompany the infuriating ease with which he lures beautiful women less than half his age into bed with him, despite resembling a deli ham with stage-III cancer of the emulsifier. That’s because the world is passing Masten by, and he knows it. In the late 1970’s, the winds of change are unmistakably blowing against retrograde macho men who like nothing better than polluting the environment, shooting the heads off wild animals, and calling cocktail waitresses “toots” while slapping them on the ass, no matter how McDuckian their net worth might be. All of that is sort of beside the immediate point, but file it away somewhere handy, because it’ll become extremely important later on.

What, then, is the immediate point? Well, Masten’s biggest business venture these days is drilling for oil beneath the Antarctic icecap using high-tech manned vehicles called Polar Borers. Imagine a more compact version of Abner Perry’s Iron Mole, and you’ll have the general idea. The last such mission ended in bizarre tragedy, though, leaving only one member of the five-man crew— junior geologist Chuck Wade (Steven Keats, from Mysterious Island of Beautiful Women and The Ivory Ape)— alive. Wade’s Borer ran offcourse somehow, and surfaced in a previously undiscovered volcanic lake well inland from the intended drilling site. The lake lay at the bottom of a valley ringed by high, steep mountains, forming a sort of air pocket in which the geothermal heat from the volcano was trapped. Even more incredibly, the ecosystem in the valley looked not merely tropical, but downright prehistoric, as if the strange, life-supporting conditions there had persisted for tens of millions of years. Wade’s four higher-ranking colleagues disembarked to have a closer look at this astonishing ecosystem, leaving him behind to watch the Polar Borer— but what he actually ended up watching was the deaths of the other scientists, as they were set upon and devoured by what Wade swears was a Tyrannosaurus rex.

An incredible story, certainly, but we can be absolutely sure at the very least that the four dead men didn’t eat themselves. At the urging of top Thrust Industries scientist Dr. Kawamoto (Tetsu Nakamura, from Atragon and The Mysterians), Masten is putting together a follow-up expedition to return to the valley, track down the otherwise extinct predator, and learn if possible whatever secrets it and its extraordinary environment have been keeping these past 65 million years. Kawamoto and Wade will be going, of course, but so will Thrust himself. It’s just way too big an adventure to sit out, especially for a guy who’s starting to feel like he too is just sitting around waiting for the next comet or asteroid strike. Masten’s attitude worries Kawamoto, and the boss’s choice for the fourth man on the team worries him even more. His name is Bunta (Luther Rackley), and he’s an old friend of Masten’s from his safariing days. To be sure, a Maasai tracker could come in handy even on a strict tag-and-release hunt, but Kawamoto can’t help thinking about all those animal heads hung up on the walls of the old man’s den just the same. After all, it’s one thing for Masten to give his word that no harm will come to the dinosaur in the calm and safety of Kawamoto’s Tokyo laboratory, but it’ll be something else again when he’s right there in that hidden Antarctic valley, within rifle range of a beast that no human has ever hunted before.

The fifth member of the team, meanwhile, will raise a whole second set of issues. Masten has already grudgingly agreed to save a seat for a representative of the press, and the reporters to whom he announces the venture are unanimous in selecting from among themselves a Pulitzer Prize-winning freelance photojournalist by the name of Francesca “Frankie” Banks (Joan Van Ark, of Frogs). You can see where this is headed, I’m sure. A dinosaur hunt is no place for a woman. Masten has never taken a woman on safari, and he isn’t about to start now. The press pool will just have to pick somebody else. All the usual tough-guy horseshit. Ultimately, though, Thrust knows he can’t actually stop Banks from coming, any more than he can undo the sexual revolution, disestablish the Environmental Protection Agency, or repeal the Endangered Species Act. Then again, maybe it won’t be as bad as he fears, anyway. Once Masten gets to know Frankie, he discovers that she’s an experienced and accomplished hunter in her own right, and any serious consideration of what it took to get most of the images and clips in her portfolio will demonstrate that she has as least as much raw physical courage as he does, and probably more. Eventually, inevitably, Masten relents, and Frankie takes her place on the team.

As is only to be expected, a lone Tyrannosaurus isn’t the only thing living in that valley that shouldn’t be. There are also flocks of giant pterosaurs, an inexplicable burrowing Triceratops, and some kind of tusked, four-horned rhinoceros which Wade hilariously identifies as “one of the cerapapsians.” The valley is home as well to a tribe of stoop-shouldered Japanese extras which we’re asked to accept as Australopithecus [although we’d say Paranthropus nowadays] robustus. One of the latter, seemingly the tribe’s only female (Masumi Sekiya), adopts an attitude toward the outsiders much less hostile than that of her menfolk, and begins tagging along after the expedition, trying to be helpful in various ways. Frankie dubs her “Hazel,” and adopts her as something between a handmaid and a pet. Naturally that annoys Masten, not least because Hazel quickly develops an unmistakable crush on him.

Thrust and his companions are going to need whatever help they can get, too, because that Tyrannosaurus proves a great deal more troublesome than they had bargained for. One morning, while Masten, Wade, Banks, and Bunta are out exploring, the dinosaur attacks their campsite, eating Dr. Kawamoto, destroying their equipment and supplies, and even absconding with the Polar Borer like a magpie collecting shiny objects with which to decorate its nest! (That last bit surprised me even more than it surprises the characters, because in 1977, very few people apart from professional paleontologists recognized the close kinship between birds and theropods.) The remaining four explorers are thus stranded indefinitely in this hostile environment, with no way to call for help, and without even the limited supply of modern conveniences (fresh clothes, nonperishable food, ammunition, etc.) that they’d been able to bring with them. Wade and Banks react to the catastrophe pretty much as you’d expect, hoping for rescue with increasing desperation while doing everything in their power to discover some trace of the Polar Borer. Masten, however, seems disturbingly pleased to be cut off from civilization. Even after Wade finds the Tyrannosaur’s lair and the Polar Borer with it, it’s clear that Masten’s ears are ringing with the Call of the Wild, to the extent that the old man can’t necessarily be trusted not to sabotage the others’ efforts to get back home.

The Last Dinosaur has one of those amazing “only in the 70’s” theme songs— that syrupy, maudlin breed of ballad that would have played on your local ear-cancer AM radio station back before it got bought by Clear Channel and started airing nothing but ranting right-wing gasbags. Think about the end-credits music from Orca, or from most of Irwin Allen’s hypothyroidal disaster flicks, if you’re unclear on what I mean. All kinds of movies had those themes back then, of course, even when the subject matter and emotional tenor of the film were in no way fitted to any such thing. Check out these lyrics, though:

| Few men have ever done what he has done |

| Or even dreamed what he has dreamed |

| His time has passed |

| There are no more |

| He is the last dinosaur |

| Few men have ever tried what he has tried |

| Most men have failed where he’s prevailed |

| His time has passed |

| There are no more |

| He is the last dinosaur |

| The world holds nothing new in store for him | |

| And things that startle you and me are just a bore to him | |

| The spark of life has gone | |

| His life grows dim | |

| Can there be something left in the world to challenge him? |

| Few men have ever lived as he has lived |

| Or even walked where he has walked |

| His time has passed |

| There are no more |

| He is the last dinosaur |

| He is the last dinosaur |

Pretty sure she’s not singing about a Tyrannosaurus there. And if The Last Dinosaur had saved the song for the closing credits like most of its ilk, we’d all nod our heads and smile at the ironic retroactive commentary: “Okay, we get it— Masten is the real Last Dinosaur.” But because this movie plays its theme song over both sets of credits, it cues us to understand the title’s double meaning right up front. This is a much less cheap sort of irony, a kind that asks for sincere engagement with its premise, and promises the same in return. It is, to say the least, unusual to encounter that kind of attention to conscious subtext in a cheesy Lost World flick pitting an elderly big-game hunter against a Tyrannosaurus rex. In kaiju eiga, though, it’s a lot less weird to see earnest examinations of serious issues juxtaposed against guys in rubber monster suits wrecking shit. This is most of what I mean when I say that The Last Dinosaur represents a disorientingly seamless melding of Western and Japanese sensibilities. On the surface, it’s goofy junk in the vein of Unknown Island or The Land that Time Forgot, but then it invites us with a straight face to think about aging and regret and the inevitability of change, and how the passage of time eventually takes everything away from all of us, no matter how much we might have started with, or how much we might amass on the way.

Mind you, that ends up being too ambitious by half for the actual abilities of the folks responsible for this film. Richard Boone, who gets completely what this movie is supposed to be about, and throws himself into it as wholeheartedly as Akira Takarada or Kenji Sahara ever did, is pretty much the only one involved who is fully worthy of the film that The Last Dinosaur wants to be. Steven Keats and Joan Van Ark appear to have no idea what their agents have gotten them into. Tetsu Nakamura is eliminated too early to bring to bear his experience with monster movies aspiring beyond their station in any useful way. And poor Luther Rackley doesn’t even get any dialogue! (We’re meant to infer, I think, that Bunta understands English, but doesn’t know the language well enough to speak it.) The attempts to build a love triangle out of Frankie, Wade, and Masten are never at all convincing, simply because it’s never remotely plausible that she’d find either man attractive. Wade is written and played as too much of an insecure man-baby, while any effort to sell Masten as some kind of Connery-esque silver fox is undone by the booze-ravaged reality of Richard Boone. Whatever Boone’s virtues (and he still had plenty of them, even in this phase of his career), no force on Earth could make that bloated old tosspot look sexy. The dinosaurs aren’t too bad from a technical standpoint (they’re certainly better than their counterparts in Legend of Dinosaurs and Monster Birds, for example), but the movie doesn’t really use any of them to their full potential. The pterosaurs don’t get enough to do, the subterranean Triceratops is too absurd to take seriously, and the “cerapapsian” is so fanciful that it belongs in some other film altogether. Even the Tyrannosaurus, rightly the best developed of the valley’s prehistoric fauna, is hampered by screenwriter William Overgard’s inability to make up his mind about what its capabilities are. Instead of being The Last Dinosaur’s Moby Dick, the T-rex comes out more like its white buffalo. Ultimately, this is another case in which you’ll have to decide which weighs more— the uncommonly ambitious stuff that it tries to do, or its inability to do very much of it in a satisfying manner.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact