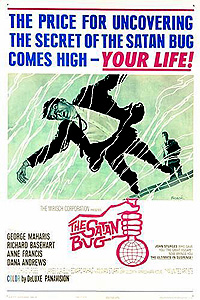

The Satan Bug (1965) ***˝

The Satan Bug (1965) ***˝

As we all know, science fiction frequently deals in prognostication. I’m sure your high school English teachers (past or present, as the case may be) will be happy to talk your ear off about all the stuff Jules Verne and H. G. Wells predicted back in their day, and how a fair number of those predictions panned out in some form or other in the years since. (Although truth be told, that isn’t the case to nearly the extent that said English teachers would have you believe. But we’ll forgive them their misconceptions— after all, there’s a reason they’re teaching English rather than science or history, right?) Most of the time, this subject comes up in the context of beneficial, or at least neutral, advances in technology— the stately march of progress and whatnot. Well, in The Satan Bug, writers James Clavell and Edward Anhalt, together with director John Sturges, made a rather grimmer prediction, and one which today seems ever more likely to come horrifically true. Rather than spinning an optimistic yarn about robotics or space flight or the groundbreaking exploration of the ocean’s depths, Clavell, Anhalt, and Sturges have trained their crystal balls on the intersection of biological warfare and stateless terrorism, positing a situation in which a wealthy nut with an axe to grind gets his hands on an inconceivably deadly artificial pathogen stolen from an army germ warfare lab. It’s a movie that has taken on an all-too-urgent relevancy of late.

It all begins one Friday evening, when a G-man by the name of Reagan (John Anderson… now there’s an odd coincidence…) pays a visit to a top-secret military outpost called Station Three, located somewhere out in the Southern California desert. Two of Station Three’s scientists— Doctors Hoffmann (Richard Basehart, from Mansion of the Doomed and The Island of Dr. Moreau) and Baxter (Henry Beckman, of Devil Times Five and The Brood)— have stuck around after hours, despite the fact that both men explicitly tell Reagan that they’re not working late tonight. Obviously something is up, and from the looks of things, Baxter probably has more than a little to do with that something. Sure enough, a few hours later, the security guards find Reagan’s dead body just outside the computer-controlled airlock of E-Lab, a hole in the wire-mesh perimeter fence around Station Three, and no sign anywhere of Dr. Baxter.

Meanwhile, a rather prickly ex-military intelligence agent called Lee Barrett (George Maharis, who went on to The Sword and the Sorcerer and the infamous made-for-TV miscalculation, Look What’s Happened to Rosemary’s Baby) is discovering that he has company aboard the boat where he seems to live these days. The man in his kitchen claims to be a representative of an organization dedicated to ending all warfare, and he has come to see Barrett because the former spy left the service precisely because of his own increasingly vocal opposition to organized violence. What’s more, Barrett’s visitor has brought with him a sealed flask of yellowish liquid, which he says contains a stolen sample of a newly developed vaccine against an only slightly less new bioweapon called Botulinus. This flask was stolen from Station Three, and its new owner hopes to be able to convince Barrett to transport it to Europe, from which point it will eventually find its way to the other side of the Iron Curtain. The idea here is to preserve the balance of power— Botulinus doesn’t do the US military any good if the Soviets have a counter to it, and thus there’s no point in it taking its place in America’s growing arsenal of unconventional weapons. But instead of cooperating, Barrett pulls a gun on his uninvited guest. Not only is Barrett personally acquainted with the peace activist his visitor is impersonating, but he also knows that Station Three doesn’t do vaccines; if that’s where the flask came from, then the liquid inside must be the Botulinus itself. No sooner does Barrett announce his intention to turn the other man over to the proper authorities, however, than he is joined aboard his boat by two intelligence agents who explain that the whole business was just a test of his reliability. You see, what Barrett is really being tapped for is a limited engagement with his old unit, turning his considerable talents toward the effort to get to the bottom of Reagan’s death and Baxter’s disappearance.

Once at Station Three, Barrett learns that the situation is potentially even graver than he realizes. As Hoffmann explains, Botulinus wasn’t the only synthetic germ he and his colleagues were working on. There is another, even deadlier, disease agent in the refrigerators of E-Lab, which has only just been developed. Hoffmann and the rest haven’t had time to christen it formally, but around Station Three, the new designer germ is known as the Satan Bug. As befits its name, the Satan Bug is easily the most lethal pathogen ever to emerge on Earth. If ever it got out into the atmosphere, all life on this planet would cease in a matter of months. Needless to say, this hadn’t been part of the team’s mission, but sometimes Tampering In God’s Domain yields unexpected results. Hoffmann’s concern is that Baxter (if indeed he is the one responsible for Reagan’s murder) has run off with the Satan Bug, or worse, accidentally exposed it to the air inside E-Lab. But how, exactly, does one find a way to peek inside the lab and find out without risking the release of the Satan Bug into the world outside the airlock?

Suffice it to say that Barrett thinks of something. And when he does, he solves the mystery of Baxter’s disappearance; the scientist is lying on the floor of E-Lab, dead of Botulinus. The trouble is, that doesn’t explain what happened to Reagan, and the guard who was on duty outside the lab last night swears he signed Baxter out. Obviously somebody found a way to infiltrate the lab, kill both Reagan and Baxter, and use the guard’s expectation that Baxter would leave the lab as the cover under which to make his escape. And as Hoffmann soon discovers, the mysterious intruder made that escape not only with all the Botulinus in E-Lab, but with the flask containing the sole extant culture of the Satan Bug as well. Barrett’s inclination is to suspect that the break-in is the work not of the KGB or some similar organization, but of someone far more dangerous than that— a disgruntled, unbalanced eccentric with ties to the agency in charge of Station Three and some kind of self-appointed messianic mission in the offing. No sooner has he put forward this thesis than a telegram arrives at the lab. Someone wants Station Three shut down and the US military’s bioweapons program discontinued, and he’s not afraid to use the Satan Bug to enforce his demands. And just to prove that he’s serious, he’s going to warm up by turning loose a plague of Botulinus on Key West and Los Angeles.

Most of the time, I’m not very fond of techno-thrillers. However, I generally appreciate them more if, like The Satan Bug, they present themselves in the guise of just-over-the-horizon science fiction. Of course, The Satan Bug itself is now alarmingly close to not being fiction anymore. If you switched out the independent psycho peacenik in favor of a Saudi suicide squad funded by a Wahhabi madrassa, and made the doomsday germ the product of a Soviet bioweapons program that fell through the cracks when the USSR disintegrated, this movie would turn into something we could very well be reading about in the newspaper next week. For that reason, I imagine a modern audience would view The Satan Bug with a far greater sense of gravity than would somebody who saw it back in 1965, when the prospect of private terrorist groups using unconventional weapons to make their presence felt was merely a theoretical possibility rather than a documented reality— before the Aum Shinrikyu cult’s nerve gas attack on the Tokyo subway system and the US anthrax-in-the-mail scare of 2001, to give just a couple of examples. But even without that grim new sense of veracity to back it up, The Satan Bug is a very impressive film. The crisis it poses and the efforts of the authorities to resolve it are handled in a mostly realistic manner, and there are no annoying personal-life subplots to get in the way. It’s difficult to overstate the importance of that last point. The Satan Bug’s characters are hip-deep in a situation that could easily mean the end of all life on Earth— they don’t have time for personal lives right now, and the filmmakers’ implicit acknowledgement of that fact is perhaps the movie’s greatest strength. This is especially true when you consider that one of Lee Barrett’s partners on the Satan Bug case is his girlfriend, fellow spy Anne Williams (Anne Francis, from Mazes and Monsters and Forbidden Planet), which seems at first like an obvious setup for just such a distraction. Compare this show of restraint to the huge numbers of contemporary espionage thrillers on the James Bond model, in which no emergency is ever so pressing that it can prevent the hero from making time to lure a succession of glamorous young women into bed with him. In a similar sense, even this movie’s biggest weakness— the somewhat lackadaisical climax— can be given a positive spin, in that the only way a situation like this could end in anything other than catastrophe in the real world would be for the authorities to get a grip early, leaving no opportunity for a high-stakes endgame confrontation between them and the terrorists. It’s just one more example of realism triumphing over mere spectacle in The Satan Bug, part of a pattern that makes this movie something different from and far preferable to the ludicrous adventure flick you might expect on the basis of its era and subject matter.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact