Mazes and Monsters (1982) -**½

Mazes and Monsters (1982) -**½

I’m cheating a little by including Mazes and Monsters in this Satanic Panic update. Don’t get me wrong, now; you won’t find a better cinematic encapsulation of early-80’s hysteria over role-playing games generally, or Dungeons & Dragons in particular, than this CBS telefilm (even if it does back away from the most lurid bits of Rona Jaffe’s novel of the same name, thereby cheating us out of Tom Hanks, Male Prostitute), and we all know how large D&D loomed in the pantheon of things Pat Robertson and his ilk had their panties in a twist about in those days. But shrill as it is, Mazes and Monsters doesn’t couch its opposition to role-playing games in religious culture-warrior terms. Rather, this movie embodies the more genteel, respectable side of the anti-D&D craze. You see, while religious conservatives were playing Pentagrams & Pentecostals, imagining themselves as courageous heroes battling the forces of Evil by making bonfires of the Dungeon Master’s Guide, a less superstitious but equally fervent group of would-be opinion-makers rose up, worrying aloud about devotees of role-playing games losing their ability to distinguish fantasy from reality. The irony was rich enough to give you gout.

The thing is, though, that the underlying psychology of the panic was the same, whether or not the panickers themselves directly invoked the name of Satan. Either way, flipping out over Dungeons & Dragons masked a fundamental mistrust of imagination on one hand, and on the other a deep-seated anxiety regarding the impact of post-nuclear family life on the nation’s youth. The former concern is easier to spot. Authoritarians of all stripes— left or right, radical or conservative, religious or secular— have always tended to look askance at imagination, because the ability to envision alternatives is the necessary first step toward questioning or resisting those in power. Combine that tendency with an ideology that insists upon crude literalism as the one true hermeneutic for understanding even so complex and self-contradictory a text as the Bible, and you’ve got an obvious formula for producing people unable to tell the difference between playing at wizardry and practicing witchcraft. Or combine it instead with an obsessive focus on the practicalities of “getting ahead,” and you get a mentality that draws no distinction between escapist entertainment and a weak-minded refusal to live in the real world.

As for family fears, remember that the Satanic Panic reached its climax by hallucinating an epidemic of “Satanic ritual abuse” within the daycare industry, with the result that totally innocent people spent years in prison for crimes that never actually occurred. Remember that these were the days when the Vice President of the United States raised a major stink over a fictional television character having a child out of wedlock. Remember the media hand-wringing over “latchkey kids” left to fend for themselves after school by working mothers, the advent of “Have You Seen Me?” photos on the sides of milk cartons, and the first blossoming of TV news departments’ ghoulish obsession with missing photogenic white girls, all of them phenomena of the 80’s. Dungeons & Dragons simply became one more ostensibly dangerous thing for unsupervised kids to get into while their mothers were out in the workforce. Mazes and Monsters is especially instructive on this point, for the movie makes the social subtext explicit. All four players of the titular game come from broken, neglectful, or otherwise dysfunctional homes, and the screenplay posits that an element of do-it-yourself psychotherapy is consciously built into M&M’s play methodology, inadequately making up for the support and guidance the players can’t get from their self-involved parents.

The first of the unhappy kids to be introduced to us is sixteen-year-old Jay Jay Brockway (Vamp’s Chris Makepeace), arch-nerd and connoisseur of outrageously terrible hats. All four protagonists are affluent (indeed, the notion of these beautiful, high-achieving scions of privilege having to role-play their way to the illusion of a fulfilling life is one of this movie’s core absurdities), but Jay Jay’s family is filthy, filthy rich. His father— whom we significantly never see— is the youngest publisher in New York City, while his mother is famous interior designer Julie Brockway (Louise Sorel). Demand for both parents’ professional services is immense, which makes the demand for their time equally so. It isn’t just competition with work that leaves Jay Jay feeling like an outsider in his own family, however. Both parents are so caught up in their own affairs that even their efforts to bestow affection are alienating. Dad once bought Jay Jay a car without realizing that the boy was too young to drive it, while Mom routinely trial-runs her latest decorating ideas in her son’s bedroom, so that his personal space is under constant threat of arbitrary disruption. Add in the social isolation that almost inevitably comes with having a tested IQ of 190 and being admitted to college at the age of fifteen, and it’s no wonder that Jay Jay’s closest friend is his myna bird, Merlin.

Nineteenish Kate Finch (Wendy Crewson, from Skullduggery and The Good Son) is probably the best adjusted of our maladjusted heroes. A child of divorce and a failure at navigating the anarchic post-70’s dating scene, she’s pretty much what young people were learning to call normal by 1982. Alone among the protagonists, Kate has a close and affectionate relationship with at least one parent, although I get the impression from the scene that introduces her mother (Susan Strasberg, of Psyche-Out and The Manitou) that the divorce settlement put Kate in her father’s custody instead.

Daniel (David Wallace, from Humongous and Mortuary) isn’t too big a mess, either. The conventionally handsome son of a computer science professor (Peter Donat, of Mirrors and Ladies and Gentlemen, the Fabulous Stains), he gets a lot of attention from girls, although it seems he mostly attracts the wrong ones for his purposes. The girls he wants to date are put off by his largely baseless reputation as a ladies’ man, while the ones who want to date him are invariably disappointed when they find themselves with an introverted intellectual instead of the golden-boy jock whom he appears to be. Daniel’s real problem, though, is his dad’s determination to have his footsteps followed in. The old man wants Daniel to become a proper engineer, but Daniel would rather put his programming aptitude to work designing video games. (Little does Dad suspect that his son’s “impractical” hobby is going to be the world’s #2 entertainment industry 20 years hence…) He certainly doesn’t feel ready for the cutthroat competition of MIT’s engineering program, regardless of his GPA at the milder-mannered Grant University, which he attends alongside Kate and Jay Jay. Daniel’s father won’t leave him alone about transferring, though, and his mother (Anne Francis, from Forbidden Planet and The Satan Bug) is more than happy to pile on whenever there’s a flareup of the old argument.

Then there’s Robbie Wheeling (a young and as-yet-unknown Tom Hanks, seen here in between He Knows You’re Alone and Splash). Torn between a belligerently disapproving father (Lloyd Bochner, from The Night Walker and Legend of the Mummy) and a drunken, regret-consumed mother (Vera Miles, of Baffled! and The Initiation), Robbie makes even Jay Jay look healthy in the head by comparison. He’s already been given the boot from Tufts University by the time he sets foot on the Grant campus, and his arrival there triggers an ominous juxtaposition. No sooner does Cat Wheeling admonish her son to stay away from “that game” now that he’s been given this second chance than we see Kate excitedly asking Jay Jay if he was able to find a new fourth player, hinting as she does so that the old one did not part from his fellows under pleasant circumstances.

“That game,” obviously, is Mazes and Monsters, and getting unwholesomely wrapped up in it was a big part of Robbie’s inability to hack it at Tufts. It’s inevitable, then, that Jay Jay, Kate, and Daniel should quickly find him, and pressure him into joining their gaming circle. Even so, things go pretty well at first— enough so that rational observers would conclude that meeting the other kids had been good for Robbie, even despite the friendship’s basis in a hobby that got him into trouble once before. Daniel runs a pretty laid-back game, and they rarely play more than twice a week. Furthermore, Robbie and Kate almost immediately develop feelings for each other, giving the boy someone to whom he can open up at last about the most traumatic experience of his life so far. A few years ago, Robbie’s older brother, Hall, ran away from home on his birthday, slipping away unseen from the Halloween party with which the date coincided. Robbie was the last person Hall spoke to before leaving, begging money for his getaway and promising to write as soon and as often as he could. In fact, though, none of Hall’s relatives ever heard from him again. Well, unless you count the dreams, that is. As Robbie somewhat sheepishly confesses to Kate, Hall shows up often in his dreams, almost as if he were dropping in from the spirit world to offer brotherly guidance and advice. About the one sign of trouble early on comes when Robbie jumps the gun by inviting Kate to move in with him, but they get past the hurt feelings engendered by her rejection of that premature offer quickly enough.

Jay Jay, however, reacts poorly to all the time Kate and Robbie are spending alone together. They and Daniel comprise essentially his entire social circle, and their twice-weekly Mazes and Monsters sessions are the only context in which he really understands how to relate to them. So when the couple begin blowing off game nights in favor of romance, Jay Jay takes it as a personal rebuff. He sinks so low as to contemplate suicide, but his flair for the theatrical will not permit him to do anything so mundane as to OD on sleeping pills in his dorm room or whatever. No, if Jay Jay is going to kill himself, he needs a stage on which to do it. After some pondering, he settles on breaking into Pequod Caverns, a former tourist trap a few miles from the Grant campus which was shuttered decades ago due to safety concerns. That ought to be a suitably lurid setting for the self-inflicted demise of a famous couple’s weirdo son! But while Jay Jay is underground planning his exit, he suddenly gets a better idea. He does still commit suicide of a sort, in that he has his character, Frielich the Frenetic, do something fatally stupid at the gang’s next M&M session, but that’s just a ploy to make his friends more receptive to the scheme that came to him in the caves. If they don’t like the idea of spinning their wheels while he creates a new character, and works him up to the same level as Kate’s Glasya the fighter and Robbie’s Pardieu the holyman, then perhaps they’d rather spin off a brand new game— one set in the real-life Maze of Pequod Caverns? Jay Jay would take over from Daniel as Maze Controller, naturally, so there’d still be the need for a new character, but since everybody would be learning a whole new style of play anyway, that shouldn’t be too big a problem. Kate, Robbie, and Daniel take a bit of convincing (they’d all be risking expulsion if they were ever caught), but the attractions of acting out their characters’ adventures in so evocative an environment are ultimately too great to resist.

This, as you might expect, is where things go awry, albeit not in the obvious senses of somebody getting lost in Pequod Caverns or maimed when the ceiling falls in on them. The first subterranean session is a huge hit with the players and a creative triumph for the Maze Controller. But it proves too immersive for Robbie, who begins losing his grip on the boundary between himself and Pardieu after “encountering” a monster from his imagination down in the caves. Guided by a figure in his dreams that calls itself the Great Hall, Robbie takes on in his daily life ever more of the holyman persona he adopts for his game sessions, eventually going so far as to terminate his romance with Kate in pursuit of spiritual purity. Finally, on Halloween night, Robbie sneaks away from a party at Jay Jay’s, exactly mirroring what his brother did all those years ago. Pardieu has been given a quest, you see: to join with the Great Hall at the Two Towers above the Underground City.

Kate is the first to link Robbie’s disappearance to his strange behavior in the preceding weeks, and to realize that Robbie has merged with Pardieu. Unfortunately, explaining that to anyone in authority would require admitting to what she and the others were doing in Pequod Caverns, virtually ensuring that they’d be kicked out of school. After much discussion, she, Daniel, and Jay Jay agree to dismantle their setup in the caves, and to tell police detective Lieutenant John Martini (Murray Hamilton, from Too Scared to Scream and Jaws) that Robbie was in the habit of playing Mazes and Monsters in Pequod. Jay Jay even contrives to give Martini the map he made of the cave system as an anonymous tip. Soon the caverns and their environs are crawling with cops and reporters, but no sign of Robbie turns up.

That’s because he’s on his way to New York City, drawn by subconscious suspicions about what became of his brother. Again Kate is the one to make the breakthrough, realizing that the “Great Hall” mentioned enigmatically in papers she and her friends salvaged from Robbie’s dorm room is not a place, but a fantastical avatar of his missing brother. That would tend to suggest that the Two Towers similarly attested might be something real as well, and not just a Tolkien reference. Before she can unravel the mystery any further, though, Robbie calls her from a pay phone at the corner of 40th Street and 8th Avenue, not far from the alley where a couple of thugs attempted to mug him. Robbie doesn’t remember that part, as he was literally not himself at the time, but it turns out that Pardieu knows how to handle muggers. The boy also doesn’t remember that the folding knife he used to shank one of his attackers in the ribs wasn’t long enough to do mortal damage. All he knows is that his hands are covered with somebody else’s blood, and it was that realization that brought him out of his delusion. Kate tells Robbie to make for Jay Jay’s uptown apartment, and rounds up the other two kids to meet him there. But when Robbie finds himself in the subway, the Great Hall’s words about the Underground City return to him, and suddenly he’s Pardieu again. Kate, Daniel, and Jay Jay will therefore have to figure out what their friend’s imaginary alter ego is looking for, in the hope of finding Robbie before he can come to any of the thousand griefs that 1982’s Manhattan held in store for the unwary.

Mazes and Monsters disappointed me with its network-TV stolidity. As a sleazy hatchet-job on an undeserving target, it gains nothing from attempting to maintain a sober, well-mannered tone. I mean, if you’re going to join up with a torches-and-pitchforks mob, at least show some enthusiasm for the enterprise! I wanted more of Robbie blundering around in skuzzy old Times Square, more of the ambitious yet shoddy dragon-man suit representing the boy’s delusions of supernatural peril, more of Martini’s bull-headed efforts to pin Robbie’s disappearance on his fellow M&M players. At the absolute minimum, I wanted to see more of the titular game, because wildly unworkable play mechanics are almost always a significant source of mirth in the forgotten mini-genre of 1980’s D&D scare stories. (An aside on this point to Hobgoblin author John Coyne: There is no way to roll 83.4 on three four-sided dice.) Mazes and Monsters has a serious “tell, don’t show” problem all around, especially during the crucial phase of the story when Robbie is actively cracking up. Apart from his dreams of the Great Hall and his sudden dumping of Kate, we learn about Robbie’s descent into weirdness primarily through his friends’ conversations. Doing things that way compounds the already implausible abruptness with which Robbie folds himself into Pardieu. It’s bad enough that it takes just one gaming session in Pequod Caverns to collapse the boy’s real and fictional identities despite a host of indicators pointing toward his improving mental health. Keeping Robbie mostly offstage from the onset of his illness until the night when he embarks on his quest, too, is just incredibly sloppy storytelling. I suppose I shouldn’t be surprised, though, at the short shrift Mazes and Monsters gives to its ostensible point, even as it lavishes energy, time, and attention on its characters’ uninteresting love lives. The source novel was something of an aberration in Rona Jaffe’s writing career, which was mostly devoted to conventional romance potboilers. Chances are the book was even worse about misapplying its narrative resources.

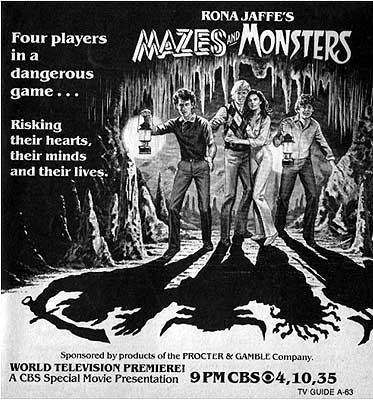

But to return one last time to the issue of Satanic Panic and this movie’s relationship thereto, let me draw your attention to a possible link hidden so far in the background that I noticed it only when I found a scan of a newspaper ad promoting Mazes and Monsters’ initial broadcast. Television airtime was still cheap enough in the early 1980’s that it could occasionally make economic sense for just one company, foundation, or organization to pick up the whole tab for a special presentation here or there. Mazes and Monsters was one of those increasingly rare single-sponsor productions, and the first-run ads identify its sponsor as Procter & Gamble, the parent company of such ubiquitous brands as Tide laundry detergent, Crest toothpaste, and Dawn dish soap. That would be the same Procter & Gamble that spent most of the past 40 years fending off wildcat boycotts from right-wing church groups in response to bizarrely persistent rumors that their CEO had appeared on a daytime TV talk show (which one varies according to which version of the hoax you encounter) to announce that the company tithed some preposterous fraction of its profits to the Church of Satan, and that their century-old Man-in-the-Moon logo was a stealthy acknowledgement of the firm’s Infernal loyalties. No one seems to know for certain where or how the Satanism libel originated, but Procter & Gamble has repeatedly sued Amway Corporation, a competitor in the market for household hygiene products as well as a pyramid scam and a tawdry cult of Supply-Side Jesus, for helping to keep it in circulation— and in 2007, a jury ordered Amway to fork over $19.25 million for doing so.

As that ought to imply, Procter & Gamble has poured a lot of money into fighting those rumors over the years. In addition to the Amway litigation, there was a meticulously documented dossier of debunking, which P&G sent out to every two-bit nest of Bible-bangers they could find, under a cover letter asking said groups to make photocopies for anyone who came to them with worries that Tide was the Devil’s detergent. The firm collected letters from talk show hosts verifying that no company representative had ever appeared on their programs, let alone used them as a platform for promoting Satanism. They enlisted a team of religious leaders including Billy Graham, Jerry Falwell, and the archbishop of Cincinnati to aver that whatever Lucifer used to polish his sulfurous fangs, it certainly wasn’t a gratis case of Tartar Control Crest. In the end, they even stopped using the trademark that had served them since 1851, on the theory that idiots might finally stop nagging them about the triple-six in the curls of the Man in the Moon’s beard if there were no more curls, no more beard, and no more Man in the Moon. And so now I find myself wondering: is it possible that Procter & Gamble’s sponsorship of Mazes and Monsters was part of that counteroffensive, too? Might the firm’s leadership have hoped to quiet the controversy by publicly joining their delusional detractors in attacking some other easy target? Was paying for CBS to air this movie Procter & Gamble’s way of saying, “See? We can’t be Satanists! If we were Satanists, why would we be just as worried as you are about that freaky witchcraft game with the tiny lead demon figures and the funny-shaped dice?” I don’t know. If so, it didn’t work very well. It would cast this crummy film in a fascinating new light, though, if I’m not just chasing phantoms here.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact