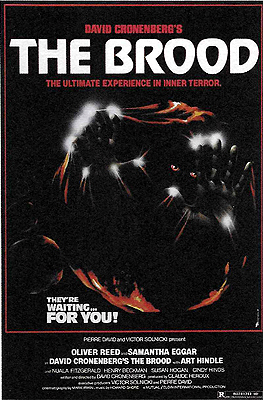

The Brood (1979) *****

The Brood (1979) *****

It’s been quite a while since I’ve reviewed a real masterpiece, and I think it’s about time I stopped torturing myself with slow-moving, mediocre movies about submarines and sea monsters. So with that in mind, let’s have a look at The Brood, one of David Cronenberg’s finest, most hard-hitting films. This was a very personal movie for Cronenberg; by making it, he was trying to work through the psychological and emotional fallout of his divorce from his emotionally disturbed wife and the bitterly contested custody battle over their young daughter which followed from it. I have no idea how the situation sorted itself out in the real world, but it’s quite clear in any case that Cronenberg came out of it with a lot of demons to exorcise. And though I’m sure his ex was none too happy to see those demons exorcised in the form of a widely released movie (albeit one that reached its audience only gradually— it took a while to convince the studio heads that they weren’t going to take a bath on this picture), we horror fans have much cause to rejoice in Cronenberg’s unorthodox therapeutic strategy. If you like your movies queasy and disturbing, The Brood is one of the great highlights of 70’s horror.

Cronenberg’s surrogate among the characters is Frank Carveth (Art Hindle, from Black Christmas and the 1978 remake of Invasion of the Body Snatchers). As the movie opens, Carveth’s wife, Nola (Samantha Eggar, of Demonoid and The Dead Are Alive), has checked herself into the clinic run by psychiatrist Dr. Hal Raglan (Oliver Reed, from The Curse of the Werewolf and The Two Faces of Dr. Jekyll), author of The Shape of Rage and inventor of a new form of psychiatric treatment which he calls “Psychoplasmics.” Psychoplasmics is basically the reductio ad absurdum of 1970’s fad psychotherapy; its central principles are role-playing and mind-over-matter. In a typical session, Dr. Raglan assumes the persona of a figure from his patient’s life whom he believes to have a central role in whatever that patient’s psychological problem is, and engages him or her in a dialogue meant to elicit an intense emotional response. What makes Psychoplasmics different from other forms of therapy is the rationale behind these dialogues: Raglan trains his patients to release their negative emotions via psychosomatic stigmata! His star patient is a man named Mike Terlan (Point of No Return’s Gary McKeehan, whom Cronenberg had used before in Rabid), a man who can cover his body with psychosomatic wounds resembling cigar and cigarette burns.

I dare say most of us would be a little bit troubled if one of our loved ones had committed herself to the care of this man before we had quite grasped the exact nature of his signature treatment, but really that’s only part of the explanation for Carveth’s increasing distrust of Dr. Raglan. One day, when his daughter, Candice (Cindy Hinds), comes home from one of her periodic visits to her mother at Raglan’s isolated clinic, Carveth notices that the girl has been injured. Her body is covered with scratches, bruises, and even bite-marks! Carveth naturally assumes that it was Nola who inflicted these injuries on Candice, and he drives up to Raglan’s clinic (which is amusingly named “Soma Free”) to inform the doctor that Candice will not be coming to visit Nola any more unless and until Raglan can provide Carveth with some kind of meaningful assurance that neither Nola nor any of the other patients will ever be afforded another opportunity to hurt her. Now most psychiatrists would be bending over backwards right about now to placate Carveth, their bowels loosening with lawsuit-inspired terror. But not Raglan. Not only does Raglan insist that Candice continue her regular visits to her mother— he says they’re essential for the woman’s recovery— he actually threatens Carveth, reminding him how easy it would be for an accredited psychiatrist to make sure Nola, and not Frank, ended up with custody of the child! Raglan sends Frank away with the warning that Candice’s visit the following week had better occur as scheduled.

Carveth’s lawyer confirms the seriousness of Raglan’s threat. The only way for Frank to get out of this bind would be to demonstrate in court that Raglan is a quack and a shyster, a danger to both Candice and Nola. It’s a tall order, but it just so happens that Raglan has at least a few former patients who are not terribly happy with him. In fact, one patient, a certain Jan Hartog (Robert Silverman, of Scanners and Prom Night), is suing Raglan for malpractice on the grounds that the stigmata aspect of Psychoplasmics is responsible for the lymphoma that is now slowly killing him. But even Hartog admits that he will probably lose his case when he goes to court; at this point, he’s just hoping the negative publicity that stems from being sued in the first place will damage Raglan’s reputation and career.

It is against this background that the real horror elements of the story begin to emerge. Frank has maintained a close relationship with his in-laws even in the face of his disintegrating marriage. Indeed, he’s closer to Nola’s parents now than she is. It is thus understandable that Nola’s mother, Juliana Kelly (Nuala Fitzgerald, from Deadly Harvest) is Candice’s primary babysitter, and Carveth leaves the girl with her when he goes to meet with Jan Hartog. While Frank is away, somebody— a midget? a child? someone small in any event— breaks into Juliana’s house and brutally murders her. The killer strangely leaves Candice unharmed. She’s been terribly traumatized, however, and is of no use as a witness when the police come to look into the slaying. The police investigation of the house doesn’t turn up even a single real clue, either.

Evidently, though, there is one place in Juliana’s house where the cops never looked, and this oversight has dire repercussions for Barton Kelly (Devil Times Five’s Henry Beckman), Nola’s estranged father and Juliana’s ex-husband. He comes to town to arrange the funeral and take a stab at getting his daughter away from Dr. Raglan. Raglan is no more willing to release Nola to Barton than he was to accommodate Frank’s fears for Candice’s safety, and the despairing old man ends up heading over to Juliana’s house to drink himself stupid while a lifetime’s worth of painful memories get together to throw a party in his head. This happens while Frank is having dinner with Ruth Meyer (Susan Hogan, from Rolling Vengeance and Phobia), Candice’s kindergarten teacher, who wanted a chance to talk with him about how his daughter was holding up under the strain of the past few months. Their dinner is interrupted by a call from Barton, who has gotten it into his head to return to Soma Free and spring Nola, by force if necessary. Realizing what an incredibly bad idea this is, Frank asks Ruth to watch Candice for a bit while he goes to Juliana’s to talk Barton down. But by the time Frank arrives, Barton has already been beaten to death with pair of paperweights by Juliana’s killer— who has been hiding under the bed the entire time. It is when Carveth confronts the killer that we get our first really good look at it (and as we shall soon see, “it” is very definitely the most appropriate pronoun); it stands about three and a half feet tall and has blond hair, dead-white skin, and yellowish eyes with pupils that are much too small for the light level in the house. It also has a harelip and horny, beak-like gums instead of normal teeth. But the most disquieting aspect of the killer’s appearance is the fact that, despite all its deformities, it still looks more than a little like Candice.

Strangely enough, the killer drops dead for no readily apparent reason soon after launching a somewhat desultory attack on Frank. The pathologist who examines the dead dwarf after the cops come determines that this is because the nutriment contained in the membranous sac on its back had been depleted— the creature essentially just ran out of gas. The doctor also calls Frank and the detectives’ attention to a number of other anatomical oddities displayed by the Kellys’ killer. It has no sex organs, its eyes have no retinas (the doctor doesn’t even want to guess as to how it might see, but he doubts that it would have had color vision), and strangest of all, it has no navel either. No navel means no umbilical cord, and no umbilical cord means that the creature isn’t human at all— its birth and gestation must have involved a process completely unlike that of human beings. Looks like Frank’s going to have one hell of a tale to tell Ruth when he finally gets back home, huh?

Yeah, well Ruth’s got a story for Carveth, too. While he was out dodging killer mutants, Nola called and accused her of trying to break up the Carveth family. Considering that we in the audience know something that the characters do not at this point— that Juliana and Barton Kelly were both killed shortly after Nola underwent Psychoplamics sessions that dealt with her pent-up rage against her parents— this gives us cause to suspect that there might be a visit from a killer midget in Ruth’s future. There most certainly is. Two creatures like the one that killed the Kellys show up at Candice’s school, kidnap the girl, and then go to work on Ruth. See, this is why kindergarten teachers usually begin the day with a roll call...

The attack on Ruth Meyer, like those on Nola’s parents, makes it into the newspapers, along with the information that the police are seeking dwarf suspects. And back at Soma Free, Dr. Raglan has been reading these newspapers. One such attack could be a fluke. Two makes for a suggestive coincidence, but still might not be worth getting too worked up over. But three attacks by psycho munchkins on people whom Nola Carveth has reason to dislike definitely constitute a pattern. Raglan, who knows more about the whole business than he’s been letting on, finally realizes how far out of hand the situation has gotten, and he suddenly closes down his clinic, dismissing all of his patients except for one: Nola herself. Frank finds out about the mass discharge through Jan Hartog, who has been keeping in touch with Raglan’s other patients, and he understandably wants to know why Raglan wants to be alone with his wife. Not only that, when Mike Terlan, the source from whom Hartog has been getting most of his information, mentions that Nola had long since taken his place as Raglan’s favorite patient, and that the doctor has Nola helping him take care of a ward full of “disturbed children,” Frank figures he knows where the midget monsters have taken Candice. Carveth shows up at Soma Free just in time to take advantage of Raglan’s change of heart regarding the therapeutic usefulness of Psychoplasmics. It is possible for a technique to work too well, and mind-over-matter coupled with psychotic rage really isn’t the sort of thing you want to mess around with lightly. If Mike Terlan can give himself burns, who knows what someone as spiteful and unbalanced as Nola might be able to do...

I think The Brood really marks the emergence of David Cronenberg as a top talent in the horror field. His previous movies were intriguing and imaginative, but never quite lived up to their potential. But with The Brood, the impact of the finished product actually exceeds what a casual observer might reasonably expect of it. The movie carries a visceral charge that has rarely been equaled before or since, and contains the most aggressive portrayal yet of that curious combination of psychological, sexual, medical, and biological horrors from which Cronenberg derives so much of his work: a mind gone bad makes a body go bad with the help of modern medicine, with hideously venereal results. The influence of the director’s own hellish experiences of marriage and divorce with a woman of questionable sanity also comes through loud and clear in the character of Nola. There’s nothing like a bad, ugly breakup to drive home to a man the utter alien-ness of women (I’m sure the converse is true, too, but Cronenberg and I are both guys, and The Brood unquestionably takes a masculine perspective on the subject), and in Nola, one can see all the aspects of femininity that most frighten, confound, and revolt the average man writ large. Her fierce, unbridled emotions and intense, unpredictable mood-swings play to men’s unease with the female mind, while the final revelation of what Psychoplasmics has made her plays even more strongly to men’s unease with the female body and the ultimately insoluble mystery of motherhood. In fact, The Brood speaks so directly and specifically to male phobias that I sometimes wonder what, if any, effect it would have on a female viewer. (I’ve never been able to convince a woman to watch it with me.) Most of The Brood’s greatest strengths stem from its deft exploitation of something that all men know, but few are willing to admit to themselves: women are scary. Because I doubt that a woman could be frightened of women in the same way (hell, I doubt that a woman could be frightened of men in the same way), it may be that The Brood would seem like just another gross 70’s horror flick to a female viewer. But it makes me squirm, and if you’re packing a Y-chromosome, I bet it’ll make you squirm too.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact