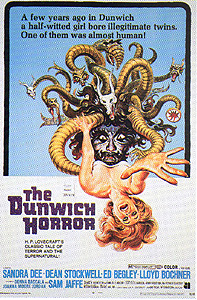

The Dunwich Horror (1970) *½

The Dunwich Horror (1970) *½

The writings of H. P. Lovecraft are another subject upon which conventional opinion and my own part company. Apart from Edgar Allan Poe, no other horror author has been so successful at winning over the mainstream literati, and among fans of the pulps— the milieu in which Lovecraft’s work was first published— only Edgar Rice Burroughs and Robert E. Howard enjoy comparable modern followings. All of which goes, in my estimation, to make Lovecraft a front-runner for the title of Most Overrated Author of the 20th Century. Now don’t misunderstand me— I want to like Lovecraft, and I’ve been trying to like him for more than a decade. But with the exception of “Rats in the Walls” and “The Hound,” I just can’t seem to do it. Part of the problem is his prose style; “cyclopean” and “eldritch” simply aren’t the kind of words you can get away with using every single time you put pen to paper, and no writer is going to win any points with me by insisting on employing grammar and sentence structure that was already archaic 50 years before his time. I’m also put off by the sense I get that Lovecraft basically spent his entire career writing the same damn story over and over and over again. On Planet Lovecraft, everybody is an obsessed antiquarian, and four men out of five are the malnourished, misanthropic, attic-dwelling descendants of evil sorcerers who were murdered by posses of their neighbors three or four generations back. Every rinky-dink town on Planet Lovecraft has some accursed spot on its outskirts where one of those evil sorcerers has tried, is trying, or soon will try to bring ancient and even more evil beings from another dimension into our world by means of incantations written in an unpronounceable tongue that was already extinct when the first Homo erectus wandered out of Africa in search of new hunting grounds. And for reasons that I absolutely cannot fathom no matter how I try, a startling proportion of the inhabitants of Planet Lovecraft keep pet black cats named “Nigger.” The sameness of Lovecraft’s stories and the impenetrable artificiality of his prose are terribly frustrating to me, because the ideas that inform his writing are fascinating. The notion that the universe was created and originally ruled by unspeakably evil monster-gods who, though long dead, have their ardent worshippers even today, and who might be restored to life by the adulation of those worshippers, has tremendous power to it. The hope that, hidden somewhere in one of the innumerable Lovecraft collections that have been published over the years, there is a story in which the author did that notion justice is what keeps me buying and reading his books. And more to the point of this review, paralleling my quixotic search are the efforts of four decades’ worth of filmmakers who have been trying with equally little success to do that notion justice by adapting Lovecraft’s stories to celluloid.

Which brings us at last to Daniel Haller and The Dunwich Horror. Haller had spent the first half of the 60’s as an art director/production designer for American International Pictures; it was he who gave Roger Corman’s Poe movies their consistently distinctive look. In 1965, he decided to try his hand at directing, and in what could have given rise to an interesting counterpoint to the Corman-AlP Poe cycle, he began by filming Lovecraft’s “The Color Out of Space” as Die, Monster, Die!, a movie that ended up owing as much to The Fall of the House of Usher and its successors as it did to anything Lovecraft wrote. It also conspicuously failed to generate any echoes of the Corman-Poe buzz, and hence did not originate a quasi-series of its own. Indeed, it wasn’t until 1970 that Haller tried again, with results that suggest he would have been better off not to have bothered.

Professor Henry Armitage (Ed Begley, of The Monitors), of Miskatonic University in Arkham, Massachusetts, has just finished up with a research project on the subject of Oliver Whateley, the supposed warlock who is the nearby town of Dunwich’s most notorious historic citizen. Armitage sends his graduate assistants, Nancy Wagner (Sandra Dee) and Elizabeth Hamilton (Brainscan’s Donna Baccala), to the library to return a rare book that was central to that research, and while they’re at it, the two girls encounter a man who is just as interested in the ancient tome as their boss is. The book is the legendary Necronomicon, that grimmest of grimoires, and is the only remaining copy known to exist. The man who wants to peruse it is Wilbur Whateley (Dean Stockwell, from The Werewolf of Washington and Dune), great-grandson of Oliver Whateley, who was said to have possessed the second-to-last extant copy. Elizabeth can tell right off the bat that there’s something amiss about Whateley, but Nancy is, shall we say, a bit more susceptible to suggestion, and she sends Wilbur off to the reading room with the Necronomicon without a second thought. The only thing that stops Whateley from walking out with the book right then and there is the arrival of Professor Armitage, who sees it under the man’s arm and stops him to ask just what in the hell he’s doing. Armitage gets a little friendlier when he finds out who he’s talking to, and invites Wilbur out to dinner with him and his assistants. He still won’t agree to lend Whateley the Necronomicon, though.

So do you really think Wilbur Whateley is going to let a little thing like Armitage’s refusal stand in his way? Hell no! Oh, and emphasis is definitely on the “hell,” there. He’ll be back to steal the Necronomicon later, but first he’s got some groundwork to lay. Using a combination of innate hypnotic powers and what appears to be some manner of love potion, Wilbur convinces Nancy to come with him to his estate in Dunwich, and to stay there throughout the following weekend. Shall we count the ways in which this is obviously a bad idea? First, there’s the fact that the Whateley manor is a dead ringer for the House of Usher (or, more appropriately, for the Curwen place in The Haunted Palace). Then there’s the Devil’s Hopyard, a funny-looking altar-like contrivance built on a stony prominence atop the hill overlooking Wilbur’s property. Wilbur also has a pair of relatives even creepier than he is. One is his grandfather, identified only as Old Whateley (Sam Jaffe, from The Day the Earth Stood Still and Battle Beyond the Stars), who carries a cheap-ass magic staff around with him everywhere he goes, and whom the townspeople of Dunwich dislike immensely. The other is Wilbur’s brother, who lives in a little room in the attic, and spends most of his time angrily rattling the locked and bolted door. You figure he might be portrayed by an embarrassingly shoddy special effect when we finally get a look at him? Good guess.

To their eternal credit, Elizabeth and Professor Armitage get worried about Nancy when she doesn’t return from driving Wilbur home from dinner that night. Driving to Dunwich, they immediately begin checking up on the Whateley family, asking all sorts of questions of the townspeople. (You know, for a man who has just finished writing a book on the subject, Armitage seems awfully ill-informed about Oliver Whateley and his kin.) In so doing, they learn that Wilbur never entertains guests, that he had a twin brother who supposedly died being born, that nobody really knows just who his father was, and that his mother, Lavinia Whateley (I Dismember Mama’s Joanne Moore Jordan), has been confined to a mental hospital ever since giving birth to her sons. Falling in with town physician Dr. Cory (Lloyd Bochner, from The Night Walker and Satan’s School for Girls) and his nurse, Cora (Talia Shire, of Gas-s-s-s and Prophecy, who was calling herself “Talia Coppola” in those days), Armitage and Elizabeth gradually come to believe that the magic of the Necronomicon and the unholy anti-gods worshipped by the Whateley clan actually exist. And if that’s the case, then Wilbur’s interest in Nancy can be explained only one way: he wants her to mother a brood of hell-spawn like him and his twin. Meanwhile, the usual pattern for such movies asserts itself again here, as Elizabeth— little more than an innocent bystander, really— opens the door to her doom (and lots of other people’s, too) by snooping around inside the Whateley mansion and setting loose Wilbur’s brother. One can only assume this second Whateley kid takes after his absentee dad...

There’s just enough upside to The Dunwich Horror to make me really pissed at how lame the rest of it is. As was almost always true of the AIP gothics that Haller had a hand in, the production design is beautiful, and belies the relatively small amount of cash that went into it. There are a few all-too-obvious matte paintings (another commonality between The Dunwich Horror and, say, Tales of Terror), but for the most part, the look of the movie is quite convincing. Haller and his people are also to be commended for eschewing the usual pentagrams and goat-imagery in the design of the Devil’s Hopyard and the assorted magical paraphernalia used by the Whateleys. Finally, while the rubber model depicting Wilbur’s brother is as crappy as they come (I can think of few other movies in which keeping the monster off-screen was such a wise decision), the device employed to indicate his presence— an intense but short-ranged wind that agitates foliage and the surfaces of ponds and streams within a small, tightly defined area— is very effective.

Otherwise... ye gods! If ever there were a movie that needed an emergency infusion of Vincent Price, it’s The Dunwich Horror. Dean Stockwell just might be the least believable warlock ever put on the screen at the behest of an actual studio. I could maybe buy him as the lead in an adaptation of The Case of Charles Dexter Ward, which revolves around a black magician who stumbles into the trade essentially by accident, and who is utterly unprepared for the travails that he has brought upon himself, but Stockwell seems much too bemused and ineffectual to portray the spawn of the Elder Gods themselves. A much more serious defect, however, is the directionless meandering that consumes most of the movie. “The Dunwich Horror” was not a long story. As Lovecraft wrote it, it would probably have been good for about half an hour of screen time— enough for one segment of a three-part anthology film, for instance, but not nearly sufficient for full feature length. So in keeping with the procedure developed for the AIP Poe movies, screenwriters Curtis Lee Hanson, Henry Rosenbaum, and Ronald Silkosky crammed the material derived from the original tale into the first five minutes and the final fifteen. To take up space in between, they could apparently think of nothing better than the magically enhanced seduction of Nancy Wagner by Wilbur Whateley. It’s the “watching the paint dry” quality imparted to the film by this gross miscalculation that really sinks The Dunwich Horror. People come to Lovecraft looking for Cosmic Evil, and Dean Stockwell trying to get laid just isn’t an acceptable substitute.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact