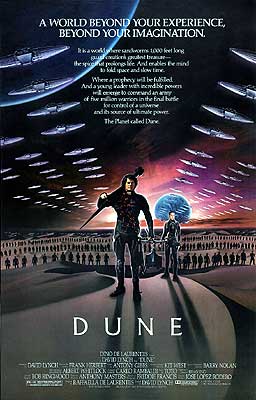

Dune (1984) **½

Dune (1984) **½

One of the best cinema documentaries I’ve seen in ages is about not the making of a movie, but how one didn’t get made. Jodorowsky’s Dune tells how maverick Spanish filmmaker and comic book writer Alejandro Jodorowsky organized what amounted to an international, interdisciplinary artists’ commune for the sake of adapting Frank Herbert’s sprawling sci-fi novel, Dune, to the screen. Just the list of collaborators whom he brought together is enough to make your head spin. Jodorowsky himself would direct, of course, and do much of the writing as well. His main partner in the latter capacity was Dan O’Bannon. The production design team included Jean “Moebius” Giraud, Chris Foss, and H. R. Giger. Pink Floyd and French prog-rockers Magma were to supply the score. And the cast was to have featured Orson Welles, Gloria Swanson, Salvador Dali, and Mick Jagger, along with more affordable talent like David Carradine, Udo Kier, and Brontis Jodorowsky (whom some of you may recall as the little boy in his father’s mad Western, El Topo). The project was extraordinary in other ways, too. Instead of a conventional script, it had a hulking tome of storyboards— essentially a colossal comic book. Assuming any slightly normal relationship between those storyboards and the completed film would yield a running time in the neighborhood of fourteen hours. And as you’ve probably already guessed, Jodorowsky and O’Bannon’s version of the story bore only the most tenuous resemblance to the source material, veering off in all kinds of contrarian directions— a fact which provoked a very public snit from Frank Herbert. Realistically speaking, there was never a chance of the movie getting made. The projected cost was prohibitive, the running time alone rendered it economically impossible, and one man’s congress of visionary geniuses is another man’s rabble of long-haired weirdos who’ll probably smoke more of the budget than will ever find incarnation in celluloid.

Still, the dream of a Dune movie wouldn’t die, even as Jodorowsky’s collective drifted apart and took their various ideas with them. (Some of those ideas would eventually find expression in other projects; Jodorowsky and Moebius’s comic book, Incal, for example, is very heavily laden with Dune leftovers.) Particularly after Star Wars proved just how big an audience a well-made sci-fi movie could attract, the pre-existing Dune fan cult made Herbert’s novel a tempting target for adaptation. It was just a question of how to make a coherent film of reasonable length out of a story that roams for years across three worlds, following dozens of characters though a labyrinthine plot in which millennia worth of cultural, political, and religious history are implicated. Okay, when I put it like that, it does sound like an awfully tall order, especially since one attempt to do so had already succumbed to unconstrained gigantism. There are some producers, though, for whom unconstrained gigantism is a way of life, and when word got out that Dune the movie was going to happen after all, nobody should have been surprised to see Dino De Laurentiis (together with his daughter, Raffaela) in back of it.

The director, on the other hand, was a name nobody would have expected to hear in connection with a would-be sci-fi blockbuster. I mean, seriously— David Lynch?!?! The Elephant Man guy?! The fucking Eraserhead guy?!?! In point of fact, Lynch had not been Dino’s first choice. When De Laurentiis acquired the Dune adaptation rights, he turned initially to Ridley Scott, then fresh from his triumph with Alien. But after grappling with Dune for a couple years, Scott decided that Phillip K. Dick was more his speed, and bailed out to make Blade Runner instead. Lynch came onboard after a screening of The Elephant Man convinced Raffaella De Laurentiis that he was indeed the director she and her father needed. Frankly, I still don’t understand the thought process there, but it’s certainly no weirder than George Lucas offering Lynch Return of the Jedi around the same time. Maybe Carlo Rambaldi— who worked with Lynch on The Elephant Man, and with Dino De Laurentiis on any number of things— vouched for him. In any case, Dune was very much a work-for-hire undertaking for Lynch, although he did get to write his own screenplay for the film. And if we may judge from his subsequent reluctance to talk about the experience, it’s not one in which he ever took a great deal of pride. I can’t say I blame him for that, even if I’m quicker to defend Dune than most people.

We begin with something baffling that will begin to make sense if you read the book. Dune might as well start that way, too, because “baffling, but begins to make sense if you read the book” is practically this movie’s mission statement. Princess Irulan (Virginia Madsen, from Zombie High and Highlander II: The Quickening), heiress to the throne of the known universe, explains that it is the year 10,191, and that the most valuable commodity in all of existence is a spice called melange that can be found only on the inhospitable desert planet of Arrakis— also known as Dune. Melange extends life, expands consciousness, and confers vast parapsychological powers when used in great quantities over a long period. When I say “vast,” I mean, for example, that the navigators of the Spacing Guild (who take so much of the stuff that it mutates them into giant tadpoles) are able to fold space with the power of their minds, circumventing the pesky physical law that limits movement to the speed of light. What’s so baffling about that, you ask? Only that it’s being laid out for us by a character who, for all practical purposes, isn’t in the rest of the movie! Apart from this monologue and a few snatches of voiceover narration later, Irulan appears only in the first scene and the last, and then only as an uninvolved observer on the sidelines. Like I said, though, it starts to make sense if you read the book. In Herbert’s hands, Irulan was a sort of Anna Comnena figure, and he began each chapter with an epigram supposedly taken from one of her many books.

Then, after the opening credits, we get— wait… Another exposition dump? Really? This one is labeled “A Secret Report Within the Guild,” and it identifies the four planets with which we need concern ourselves for the next two hours and change: the aforementioned Arrakis; Caladan, the home of House Atreides; Giedi Prime, the home of House Harkonnen; and Kaitain, the Universal Capital. The report goes on to hint at developments on those worlds which threaten to disrupt spice production, and concludes by stating that a high-ranking navigator is on his way to Kaitain even now to interview Padishah Emperor Shaddam IV (Jose Ferrer, of The Amazing Captain Nemo and The Swarm) about whatever it is that has the Spacing Guild so concerned.

Now brace yourself, ‘cause we’re about to dive deep into interplanetary power politics. It turns out that the Emperor of the Known Universe is a limited monarch despite his hugely impressive title, and that he shares power with an assembly called the Landsraad. The latter body apparently speaks for the Great Houses, which are the Imperium’s hereditary nobility. There’s also a religious order called the Bene Gesserit, but we’ll get to them in a bit. One of the Great Houses, the Harkonnens of Giedi Prime, used to administer Arrakis as an imperial fief, but Shaddam recently annulled their contract and installed their enemies, House Atreides, on Arrakis instead. That’s because the emperor has grown leery of the rising influence of Duke Leto Atreides (Jürgen Prochnow, from House of the Dead and Judge Dredd) in the Landsraad, to say nothing of rumors that Caladan has introduced a new model army equipped with some kind of sonic weaponry that could make them a match for the imperial Sardaukar terror troops. By sending the duke to Arrakis, Shaddam not only separates him from his power base, but also stokes the rivalry between the Atreides and the Harkonnens. Then, after a suitable interval, the emperor will lend Baron Vladimir Harkonnen (Kenneth McMillan, of Cat’s Eye and Salem’s Lot) five legions of Sardaukar and turn a blind eye while he retakes his family’s old Arrakis concession by force. The emperor assures the navigator that there’ll be no more than a blip in spice output while his machinations take their course. The navigator agrees on behalf of the Spacing Guild not to interfere, provided Shaddam takes special care to ensure that the duke’s son, Paul (Kyle MacLachlan, from Showgirls and Xchange), is killed in the fighting. Now that’s weird. Paul Atreides is just a kid; why would the Spacing Guild want him eliminated? The emperor’s Truthsayer, the Bene Gesserit Reverend Mother Gaius Helen Mohiam (Sian Phllips, from Clash of the Titans and Ewoks: The Battle for Endor), determines to find out.

And I guess that means we have to talk about the Bene Gesserit now, don’t we? This bunch are more than just an order of weirdo space nuns. By using another mind-altering Arakeen product called the Water of Life, they’ve given themselves telepathy, precognition, and a superhuman suggestion power called the Voice. But more importantly, they have an agenda, too. For 90 generations, they’ve been pulling the strings behind noble marriages within the Imperium in the hope of breeding a man they call the Kwisatz Haderach, a sort of eugenic messiah. They’re very close now— so close, in fact, that Mohiam dares to hope that the child of an Atreides daughter and a Harkonnen son would be it at this point. The Bene Gesserit therefore saw to it that Duke Leto would take as his concubine one of their own agents, a woman called Lady Jessica (Francesca Annis, from The Eyes of Annie Jones and The Pleasure Girls). Jessica was supposed to bear only daughters so as to force the required union between the two houses, but in the end, she decided she cared more about Leto’s desire for an heir than she cared about her mission. Thus Paul. It occurs to Mohiam that the fears of the Spacing Guild might be taken as evidence that Paul himself has Kwisatz Haderach potential, and the test to which she puts the boy yields highly suggestive results. Suggestive enough, indeed, to set the Bene Gesserit order against the Guild’s plot to have him killed.

Now Duke Leto is not a stupid man, and neither is his chief advisor, the mentat (or human computer) Thufir Hawat (Freddie Jones, from The Satanic Rites of Dracula and Krull). They both know they’re walking into a trap on Arrakis, and they have no intention of letting it close on them. Leto therefore sends one of his best men-at-arms, Duncan Idaho (Richard Jordan, of Logan’s Run and Solarbabies), to Dune ahead of the rest of the household to scope out the place. Above all, Duncan is to make contact with the Fremen, the proud, nomadic race that dwells in the planet’s deepest deserts, where no human should be able to survive between the heat, the aridity, and the thousand-foot sandworms. Anybody that tough is someone Leto badly wants on his side. He also orders Gurney Halleck, another of his finest fighters (Patrick Stewart, from Mysterious Island and Lifeforce), to step up Paul’s military training, both in Caladan’s traditional knife-and-forceshield martial arts and in the new sonic weaponry.

All that shrewd preparation comes to naught, however, for there is a traitor in the Atreides’ midst. Baron Harkonnen has a mentat of his own, a cruel and perverted man called Piter De Vries (Brad Dourif, from Spontaneous Combustion and Alien Resurrection), and Piter has done something that’s supposed to be impossible. He has overcome the Imperial Conditioning (a psychological discipline intended to make the recipient incapable of doing deliberate harm to another human being) of Dr. Yueh, the Atreides court physician (Dean Stockwell, of The Dunwich Horror and The Nest). De Vries did… things to the doctor’s wife, you see, and the only way Yueh can be sure that those things have come to an end is by betraying his beloved master. When the time comes, Yeuh will sabotage the defenses and fortifications of the ducal palace, permitting the Harkonnen forces to enter virtually unopposed. And in the aftermath, the baron will leave Arrakis to the none-too-tender mercies of his dim but deadly nephews, Raban (Paul L. Smith, of Red Sonja and Pieces) and Feyd-Rautha (ex-Police frontman Sting, whose other forays into acting include The Adventures of Baron Munchausen and The Bride).

The time comes much faster than Duke Leto is prepared to handle, too. His sonic army is still settling into its new barracks. Thufir Hawat is still scrubbing the palace and its environs clean of Harkonnen booby traps. The overtures to the Fremen have barely begun. Hell, Leto is only just starting to win the trust of Dr. Liet Kynes (Max Von Sydow, from Needful Things and Star Wars: The Force Awakens), the imperial planetologist who’s gone full native since arriving on Arrakis, whom the duke was counting on as a shortcut to the Fremen’s good side. Baron Harkonnen’s plan goes off with very few hitches, and at first it looks like that’s probably true of the emperor’s plan as well. But Dr. Yueh has lain the groundwork for a revenge more magnificent than even he suspects. Amid the chaos of the Harkonnen conquest, he arranges for Paul and Jessica to escape into the deep desert equipped to survive as the Fremen do, at least for a little while. When the fugitives make contact with the Fremen tribe led by Dr. Kynes’s friend, Stilgar (Everett McGill, of Silver Bullet and Quest for Fire), they are welcomed after a somewhat tense start, and over the next several years, Paul and Jessica assimilate into Fremen society at least as thoroughly as the planetologist. Jessica becomes the tribe’s Reverend Mother, and Paul becomes the lover of Chani (Sean Young, from Headspace and Blade Runner), a fierce female fighter. More importantly, it turns out that the Bene Gesserit aren’t the only ones awaiting a messiah. The Fremen too have legends and prophecies of a superhuman savior, and between the genes carefully marshaled to create him and the consciousness-warping effects of the spice-rich Fremen diet, Paul starts to look a lot like the guy Stilgar’s people have been praying for. Duke Leto’s dream of a Sardaukar-slaughtering Fremen army will be realized after all, even if he doesn’t live to see it himself.

I can’t deny that Dune is a tangled, disorderly, overly hurried, and frequently bewildering mess. It’s the only movie I’ve ever seen where they handed out cheat-sheets at the theater— and that was just the last step in a multilayered and ultimately unsuccessful effort to render the institutions and terminology of Frank Herbert’s universe comprehensible to audiences that hadn’t already read the book. Other aspects of that campaign include the opening monologue and recurrent narration by Princess Irulan, endless whispering voiceovers meant to reveal what this or that character is thinking, some good old-fashioned exposition dumps in the original dialogue, and even a tacky curtain call in the closing credits affording one last chance to match names to faces among the film’s 500 or so major characters. However, it’s immediately obvious that these intended aids to comprehension were added on an ad hoc basis at different times throughout Dune’s production, because there’s no coordination among them. Characters repeat verbatim points that were already covered in the narration, while those raspy interior monologues state the obvious one moment only to leave some crucial point unexplained in the next. For instance, one of Jessica’s audible thought-bubbles calls attention to Dr. Yueh’s Imperial Conditioning without bothering to explain what that is, so that only those who already know the story will understand why it’s such a big deal that the Harkonnens have suborned him— but it laboriously connects the dots for us regarding why the doctor is overcome with emotion whenever he mentions his wife. Dune is that rare film that can leave you utterly in the dark even as it insults your intelligence.

But let’s say you did your homework and read the novel; how does Dune look then? If I thought there were such a thing as a non-purist fan of literary science fiction, I would expect most of them to find this movie generally adequate, if rather too short. The majority of the book is present in some form, although a few things (like the ecological relationship between the spice and the sandworms) get harmfully short shrift, while others (like the Sardaukar and the Atreides Weirding Way of Battle) have been altered enough that it may take a second viewing to recognize them. I’ll even go so far as to say that some of Lynch’s changes qualify as improvements. For instance, I so like his vision of the Sardaukar as nigh-indestructible poison-gas zombies (complete with body bag-like environment suits to hold in the toxic fumes they need to breathe) that I was disappointed to discover, upon reading the book, that Herbert rendered them merely as men toughened nearly to the limits of human capacity by life on the second-worst nominally habitable planet in the universe. (Look closely at that description, and you’ll see why the Fremen are able to beat the imperial terror troops in Herbert’s telling; Salusa Secundus is nasty, but it isn’t as nasty as Arrakis.) I’m also fond of Lynch’s much weirder and yet more readily explicable interpretation of how the Spacing Guild navigators use the spice, although it lacks the original thematic tie-in with how the spice affects Paul. I mean, come on— isn’t getting so high that you can tie a knot in the universe with the power of your mind a lot cooler than circumventing the limits of human reaction time because you can precognitively see the quantum waveform of the future, even before you factor in dope so gnarly that it turns you into a giant tadpole? Then there’s the Lynchiest part of the film, the baroque exaggeration of the Harkonnens’ depravity. Make no mistake, Herbert’s Harkonnens were not nice people, but they’ve got nothing on the richly layered foulness of this bunch. It takes the imagination that brought you Eraserhead to dream up having externally accessible valves installed in the hearts of all your employees, so that killing them in a fit of pique becomes a simple matter of pulling the plug. On the other hand, I’m less crazy about treating the Weirding Way as a technology instead of a fighting technique— not because a word-gun that blows things up or melts them or sets them on fire depending on what you say into it isn’t boss, but because this movie could have climaxed with giant kung fu fight between Paul’s Fremen army and the aforementioned poison-gas zombies. Don’t even try to convince me you wouldn’t want to see that.

The one issue on which I absolutely can’t argue with disgruntled purists is the nature of the Kwisatz Haderach. Simply put, either David Lynch missed the point entirely, or he rejected it equally entirely. Probably the cleverest thing Frank Herbert did in Dune was to turn the hoary old Chosen One narrative inside out by constantly reminding the reader of the Bene Gesserit order’s role in manufacturing both the prophecies and the man who supposedly fulfills them. In the novel, there’s no magic, no destiny. There’s just a bunch of far-seeing women exploiting human superstition on one hand while attempting to steer post-human evolution on the other. If Paul Atreides seems to embody the promises of Fremen religion, it’s because the Bene Gesserit seeded that religion and a thousand others like it in anticipation of the day when their centuries-long eugenics project reached fruition. In the movie, however, the Kwisatz Haderach is a genuine living god, and although the Bene Gesserit brought him about, they seem to have done so as an act of faith rather than an act of hubris. Here the hubris lies instead in Reverend Mother Mohiam’s expectation that the Kwisatz Haderach will be hers and the emperor’s to command.

The majority of Dune’s defects are traceable to Universal’s insistence on a running time that rounded down to two hours. Lynch started off aiming for three, which was probably the absolute minimum necessary to tell this story without major pruning, but he understood from the get-go that his contract with De Laurentiis and the studio didn’t grant him any say over the final cut. So when the grumbling started over the screening per day that the extra running time was going to cost, Lynch didn’t put up much of a fight. The great frustration of Dune is thus that no director’s cut is even theoretically possible, because much of what would have gone into it was never shot in the first place. The three-hour alternate cut that surfaces occasionally on TV was created by tossing in every scrap of remotely usable footage, including a fair amount that was never technically finished. (Note, for example, that the Fremen characters in the long version frequently lose their distinctive blue-within-blue-within-blue eyes. The Fremen eyes were an optical effect added in post-production, so their absence marks footage that was condemned to the cutting room floor before principal photography wrapped.) Although it has been passed off from time to time as the more legitimate edit, the truth of the matter may be judged from the opening credits: “Written by Judas Booth” and “Directed by Alan Smithee.”

In either major version (there are myriad minor variations on each, depending on the market and release format), what most holds Dune together is its truly outstanding production design. Even when a particular set element or special effect looks cheap and shoddy— which happens far too often for a $46 million film— the underlying concept is almost always a triumph of visual imagination. Even without the involvement of Jodorowsky’s conclave of fantasy-art luminaries, Dune displays not one but several unforgettable esthetic personalities, from the Space Habsburg grandeur of the imperial court to the charnel hideousness of Giedi Prime to the sweaty severity of Arrakis itself. What’s more, all of those different vibes have a distinctly 70’s Eurocomics edge to them, which really made them stand out in the more practical-minded context of 80’s science fiction. I think that more than anything accounts for my undying affection for this troubled and uneven picture. As with The Black Hole, Dune’s stunning looks encourage you to imagine the film it doesn’t quite manage to be.

With this review, I join my fellow B-Masters in celebrating producer Dino De Laurentiis, the schlock-movie titan who married the slapdash, try-anything audacity of the Italian cinema industry to the megalomania of Hollywood. Click the link below to read my colleagues’ thoughts on the subject.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact