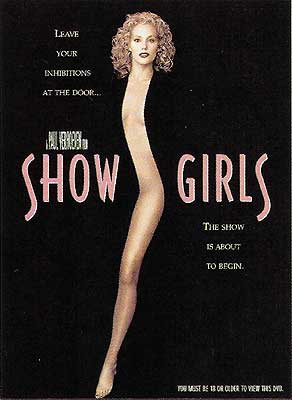

Showgirls (1995) -***

Showgirls (1995) -***

If you hang out, as I do, among bad-movie hobbyists, somebody sooner or later is bound to ask you what’s the worst thing you ever paid full price to see in the theater. It impresses me sometimes that my answer has remained unchanged since 1995: it’s Showgirls, no question. Showgirls is also my answer to “What’s the worst [and/or most wildly inappropriate] movie you ever saw on a date?” although with that one, I can plead the rather astonishing extenuating circumstance that it was her idea. That’s the part that really throws people. Even given my pronounced taste for trashy women, how on Earth did I ever find myself taking a date to see this outrageously crass, sleazy, exploitive, and reprobate film at her instigation?! To understand that, you have to understand how assiduously Showgirls had attempted to hoodwink the ticket-buying public before its premiere, which in turn requires some familiarity with the development of adults-only movies in America during the 27 years preceding that premiere.

Remember that in 1968, the Motion Picture Association of America, then under the direction of Jack Valenti, succeeded at last in devising a workable replacement for Will Hays’s old Production Code, the increasingly ludicrous set of industry self-censorship guidelines promulgated originally in 1930 (and first rendered meaningfully enforceable in 1934). The outdated censorship code was superseded by a four-tier rating system in which anything that would have passed muster under its predecessor was rated G for general audiences, while the three higher tiers covered various degrees of adult content: M (admission unrestricted, but recommended for mature audiences), R (admission restricted to those sixteen and older unless accompanied by a parent or guardian), and X (no one under sixteen admitted). There was some tinkering over the ensuing years, but the system as a whole has proven remarkably durable. Indeed, most of the changes have been unofficial, tacit shifts in the boundaries between ratings that have kept pace, for better or for worse, with the zeitgeist concerning various sorts of content. And the few official changes have tended to be sensible in concept, even if they’ve led to questionable applications. The cutoff ages for the top two ratings were raised to seventeen and eighteen respectively. M was recodified in 1970 as GP and then again in 1972 as PG (parental guidance recommended), acknowledging that the original G rating was perhaps too broad. A fifth tier, PG-13, was introduced in 1984 to do approximately the M rating’s old job. But the most persistent problem, remaining effectively unsolved to this day, was the administration of the system’s adults-only rating.

It seems weird, but the MPAA never filed a trademark on the X-rating. Evidently they didn’t want to burden the ratings board with every scumbucket exploitation flick to come down the pike, especially with pornography slipping loose from its accustomed legal restrictions in jurisdiction after jurisdiction. The hope was that the vilest schlockmeisters would self-impose their own Xes if given the freedom to do so; the trouble was that they did. Indeed, hardcore pornographers soon began claiming bogus XX and XXX ratings for their product, bragging that their letter was more scarlet than the other guy’s. The 1970’s had barely begun before all that exuberant X-mongering permanently tainted the public perception of the rating. Owners of non-pornographic theaters started refusing to play X-rated movies. Mainstream media outlets started refusing to advertise them. And when home video became a factor in the 1980’s, the biggest rental and retail chains made it a policy not to stock them on their shelves. Even the ratings board itself got into the act, using the stigma of X as a weapon against independent producers with little clout in the industry, who hoped to compete with the big boys by trading on a higher pitch of sensationalism. The “X is for porn” mentality thus effectively discouraged the creation and distribution of genuinely adult pictures. Filmmakers were forced to choose between censoring themselves to get an R and accepting that their work would play strictly on the ever-shrinking arthouse and grindhouse circuits— neither one of which might be a suitable environment for it. The untenability of the situation was brought into stark relief in 1989, when Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer and The Cook, the Thief, His Wife, and Her Lover both won critical acclaim, but had to be released unrated (which carried penalties of its own) in order to escape being bundled together with the likes of Sextectives and Oral Majority 7. The MPAA had rendered itself incapable of coming to grips with movies that dealt unflinchingly with the subjects of sex and violence unless they were sleazy and exploitive.

Thus it was that in 1990, the organization scrapped the open-source X rating, and replaced it with the duly trademarked NC-17. The theatrical market for porn was moribund anyway by that point, so there was no more reason to fear having to sit through a million numbing parades of ineptly shot copulations, and the first few films to carry the new rating were very much in the intended vein. But there was still something of an experimental quality to NC-17. Henry and June and its mostly European contemporaries were all small movies, consciously aimed at specialist audiences. Until 1995, there was no serious attempt to take NC-17 big, to test its viability as a non-pejorative statement of content in the unforgiving ecology of wide, commercial release.

That’s where Showgirls came in. Showgirls was nothing if not big. It was developed by Carolco (which succeeded Cannon as Hollywood’s foremost independent studio) before being sold to MGM/UA, and its reported production cost topped $45 million. It opened on 1388 screens nationwide, including seemingly unlikely places like the Harbor Nine multiplex in suburban Annapolis. It was marketed in magazines, newspapers, and network television, all media that had traditionally shunned adults-only films in the pre-NC-17 era. And the creative team behind it were themselves larger than life. Paul Verhoeven was deservedly regarded as the day’s great auteur of excess, and screenwriter Joe Eszterhas was the first Hollywood scribe that I can recall attaining the kind of public visibility enjoyed by star directors. Together, they had already racked up one monster success de scandal with Basic Instinct. If anybody could make an NC-17 blockbuster, it ought to be those guys, right? Weeeeell…

Nomi Malone (Elizabeth Berkley, later of S. Darko) is hitchhiking her way westward to Las Vegas. As she explains to the skeezy wannabe cowboy who picks her up for the last leg of the journey (Dewey Weber), she wants to be a dancer in some big casino hotel’s T&A revue, but more interesting than Nomi’s peculiar aspiration is that she appears to be a sociopath. Granted, I’ve never gone hitchhiking in my life, and I don’t pretend to be an expert on the relevant etiquette. Still, I’m willing to bet that pulling a switchblade on the person giving you a ride is generally considered an excessively confrontational response to being asked your name, no matter how big a smarm-monster the person doing the asking might be. Jeff (for that is the wannabe cowboy’s name) sensibly pulls his truck over at once, and tells Nomi that she can just get the fuck back out onto the road if that’s how she’s going to act. Temporarily chastened, Nomi puts her knife away, and manages to be almost civil to Jeff for the next 342 miles. It even seems that their meeting might be a lucky break for Nomi, because Jeff claims to be the nephew of a host at the Riviera— maybe he can pull a string or two to get her a job as a cocktail waitress or something. It’s possible he was telling the truth, too, since he does indeed take her to that hotel, but while Nomi amuses herself playing the slots (in what passes around here for subtle foreshadowing, she scores big on the quarter machines, but then loses every cent of her winnings playing silver dollars), her supposed benefactor slips away and takes her suitcase with him. All is not lost, however, for the girl whose car Nomi assaults during her subsequent temper tantrum in the Riviera parking lot is a candidate for sainthood, and offers to take her in once she’s calmed down enough to explain what just happened.

Nomi’s new roommate is named Molly Abrams (Gina Ravera, of Kiss the Girls), and she’s a professional-caliber seamstress. In fact, she works as the wardrobe mistress for shows at the Stardust, keeping all the dancers’ G-strings in good working order. Her talents also benefit Nomi, insofar as she enables the latter girl to dress like a high-priced call girl on a crack whore budget. I shouldn’t let Nomi hear me say that, though— she takes violent exception to being compared to a prostitute in any price range. It’s inconvenient for her, then, that the only dancing gig she can hustle up is one riding the brass pole at the Cheetah, a large but fairly revolting strip club where proprietor Al Torres (Robert Davi, from Illicit Behavior and Predator 2) demands regular blowjobs from the staff as a condition of employment.

One night, Molly takes her roommate to work with her. Watching Goddess (the current Stardust revue) from a privileged, staff-only vantage point reinforces Nomi’s ambition to shake her tits for a higher class of voyeur, but it doesn’t go well when Molly brings her backstage to meet Cristal Connors (Gina Gershon, of Prey for Rock & Roll and Voodoo Dawn), the lead dancer. Cristal dismisses her at once as a mere sex worker (“I don’t know what it is you’re good at, darlin’, but if you do it at the Cheetah, it ain’t dancing.”), sending her into such a snit that there’s nothing else for it but to blow off work, go out clubbing, pick a fight with a bouncer, and get arrested. Fortunately, James Smith, the aforementioned bouncer (Glen Plummer, from Strange Days and Monsters in the Woods), apparently likes girls who kick him in the balls and get him fired from his job. He comes by the jail to bail Nomi out the next morning, and tries to interest her in collaborating with him on his latest project.

James, you see, aspires to be a producer of lewd entertainments, and he thinks Nomi would be just perfect for the female lead in his one-number show, A Private Dance. They’ll spend much of the first act sparring over the issue, but I’ll be damned if I can tell you what Nomi’s objections to signing on are supposed to be. Part of it may be the simple fact that James thinks she needs training and discipline to reach her potential, only that’s so manifestly true that it makes Nomi look delusional for taking offense at it. Part of the problem could also be James’s inability to compartmentalize training his dance partners from dating them, except that Nomi can’t seem to compartmentalize those states either. The final rupture between them comes when James gets tired of her vacillating, and starts grooming her fellow Cheetah girl, Penny (Rena Riffle, from Satan’s Princess and Bound Cargo), for the part instead. And even then there’s no making sense of Nomi, because she’s the one who gets pissed off at him for involving another dancer in something that she clearly didn’t really want to do in the first place.

Besides, Nomi has always had her sights set a lot higher than A Private Dance. Despite her manifest lack of qualification for the job, she wants to dance in Goddess at the Stardust. Luckily, Cristal Connors also happens to like her for no obvious reason, and spends the weeks after their introduction relentlessly insinuating herself into the younger woman’s life. First she comes by the Cheetah with her boyfriend, Goddess producer Zack Carrey (Kyle MacLachlan, from Dune and The Hidden), and spends a fortune hiring Nomi for a humiliating lap dance. Next, she uses her influence to get Nomi an audition with casting director Tony Moss (Alan Rachin, of Time Walker and Terminal Voyage)— which is not without humiliations of its own— and maybe even to secure her hiring. Everyone on the staff at the Cheetah is very sorry to see Nomi go, especially Henrietta Bazoom (Lin Tucci), the combative, auto-misogynist insult comic. (Have I mentioned yet what a bizarre down-market titty bar the Cheetah is? It’s almost as if neither Verhoeven nor Eszterhas had ever set foot in such a place.) Even then, Cristal’s intervention in Nomi’s life doesn’t stop, nor does the pattern whereby every new largess carries a high price in dignity and self-respect.

Meanwhile, in the background, we are also privy to the ongoing feud between Cristal’s turbo-bitch understudy, Annie (Ungela Brockman, rather more visible here than she would be later in Starship Troopers and From Dusk Till Dawn), and another, slightly less bitchy dancer called Julie (Melissa Williams, from Women of the Night and Between the Lies). At first their rivalry just looks like local color, but around the time that the weirdness between Nomi and Cristal blossoms into a full-on hate affair of barely suppressed lesbianism, Julie takes decisive action in revenge for Annie’s mistreatment of the other woman’s two children. In the middle of a number that has all the girls being carried around overhead by their male partners, Julie releases a handful of glass beads into the path of the guy toting Annie. He slips, she falls, and her kneecap shatters into a zillion pieces even though she unmistakably lands on her ass. With the understudy position now open, Zack (who is by this point fucking Cristal and Nomi alike) pushes Nomi to apply for it, and when Cristal puts the kibosh on that latest bid for advancement, our heroine decides to take Julie as a role model. A good fall down the backstage stairs leaves the Stardust without a star, and Zack convinces the owner to take a gamble on Nomi.

Now that Nomi’s rise is complete, you’d expect the rest of the movie to concern her fall, but that’s not quite what happens. Although the hotel’s vetting staff do turn up the past indiscretions that she’s been covering up so neurotically ever since she refused to reveal her name in the opening scene, the revelation causes her little actual harm, since it does no more than to confirm what everybody— characters and viewers alike— already suspected. Instead, the third-act drama revolves around Molly (remember her?), who comes to grief when her favorite crooner, Andrew Carver (William Shockley, from Street Asylum and Howling V: The Rebirth), puts on a show at the Stardust. Nomi thinks she’s doing her friend a favor by introducing her, especially when it turns out that Carver is the sort of performer who takes that kind of interest in his fans. But what both girls fail to realize until it’s too late is that Andrew can’t get it up unless the sex is nonconsensual. Molly is in pretty bad shape by the time Carver and his bodyguards are finished with her. That sends Nomi onto the warpath, and the next thing we know, Showgirls has turned itself into a big-budget, sublethal riff on Ms. .45. Naturally the Stardust isn’t going to stand for one of its star entertainers putting the other one in the hospital, so Nomi skips town for Los Angeles— hitching a fortuitous ride from a certain wannabe cowboy suitcase thief, no less! That conclusion puts a truly delightful notion into my head: what if this story has been repeating itself, in ever more grandiosely sordid terms, in every major city along the interstate southwest from Buffalo?

Showgirls did alright on opening weekend, grossing better than $8 million— $15 or so of which were mine and my ex’s. Then the people who bought those tickets started talking, and it was all downhill from there. As virtually everyone was quick to point out, this attempt to take adults-only cinema both upscale and into the mainstream had resulted in a product every bit as tasteless, tawdry, stupid, hateful, and inept as anything David Friedman had served up during the bad old days of the X rating. Showgirls had revealed itself to be just as adolescent in its outlook, just as stunted in its attitude toward sex, just as contemptuous of women, and just as thoroughly suffused with moronic, smirking vileness. Furthermore, it wasn’t even sexy, despite all the roving packs of gyrating, nude women and several of the most explicit softcore couplings ever seen in a big-studio film. In the end, the movie recouped less than half of its production cost in five weeks of domestic release, and even the international box office was powerless to bring it into the black. Worse, Showgirls more or less singlehandedly convinced the American public— along with the media, the advertisers, the video retail and rental chain owners, etc.— that there was no meaningful difference between NC-17 and X after all. The new rating thus became, almost overnight, an onus to be avoided by filmmakers seeking mainstream acceptance just like the old. Having been given a chance to prove that adults-only cinema could learn to comport itself in polite company, Verhoeven and Eszterhas jizzed all over the good tablecloths, and Hollywood remains as inhospitable an environment as ever for grownup movies about grownup subjects.

That said, everybody who enjoys a good traffic accident, sports riot, or fertilizer plant explosion really ought to see Showgirls at least once. No other movie I know of in this price range has ever been bad in quite this combination of ways before or since. To begin with, its protagonist is an utterly loathsome and unsympathetic person who learns nothing and gains nothing as a result of her experiences, yet we’re asked in the end to believe that the new Nomi is much wiser than the old just the same. Witness this exchange of dialogue between her and Jeff when he gives her a lift the second time:

“Did you gamble?” he asks her.

“Yeah,” she replies.

“What did you win?”

“Me!”

And to prove how much Nomi has grown and changed, we’re then treated to an exact reprise of the first hitchhiking scene, switchblade and all.

What’s fascinating is that Showgirls attempts through Nomi to cloak itself in several different narrative and thematic templates, but not one of them actually fits. It wants to be a loss-of-innocence story, but that won’t work, because Nomi was never innocent. It wants to be a cautionary tale of showbiz exploitation, but nobody does anything to Nomi that she wouldn’t do to them in a heartbeat if given the chance. It can’t even work as a simple “rise and fall of a star” story, because as I said, Nomi never properly falls. She just has to go on the lam eventually, because she beats the shit out of somebody famous and locally powerful.

It should surprise no one, then, that the young and relatively inexperienced Elizabeth Berkley is utterly defeated by her part. She gives it her all, bless her, but it’s a hopeless task. She can’t be likable, because her character is written so as to vacillate between spoiled brat and complete monster. She can’t play to Nomi’s sociopathy, because the script gives her no room even to acknowledge it. And on top of everything else, she’s surrounded by people talking up Nomi’s natural star power and talent for dancing, even as Berkley demonstrates again and again that she has none of either. Inevitably, Showgirls did not do for her what Basic Instinct had done for Sharon Stone.

Gina Gershon comes out rather better, because she was perceptive enough to realize what a roaring dumpster fire Showgirls was shaping up to be. As she put it herself, “I initially thought that it was going to be really dark and really intense, and then it turned out to be completely different. So instead of going in that direction, I decided to make it so that drag queens would want to dress as my character on Halloween.” I don’t know any drag queens, so I can’t say how successful she was there. I can tell you, however, that there hasn’t been such a spot-on performance of female impersonation by a woman since the heyday of Mae West. It’s all the bitchy Texas “darlin’”s that really put it over the top, I think. And Gershon’s rendition of Cristal playing off Berkley’s rendition of Nomi is a sight to behold, even when they aren’t overtly flirt-fighting or fight-flirting. The two women comparing notes on their favorite brands of dog food over lunch is a memory that you will carry with you to your grave.

Gershon’s deliberate subversion of her own role brings me to a theory I have about Verhoeven’s attitude toward his collaborations with Eszterhas. Especially in Showgirls, but to an extent in Basic Instinct as well, I get the sense that the director also understood how puerile and trashy the script was, and sought to send it up without letting on that he was doing so. That sounds complicated, but it would be simple enough with Joe Eszterhas; you just film what he wrote, as he wrote it, and let nature take its course. In Showgirls, letting nature take its course yields a Bizarro World without cause and effect as we understand them, where normal human behavior is worthless as a predictor of character interaction, where moral and ethical principles have apparently been arrived at via guesswork by aliens who no more understand our life experience than we can understand that of a slime mold. It’s like a $45 million version of The Room.

And like The Room, it seems that Showgirls has finally begun to find the audience that eluded it on its release— the irony being that it’s the very one the film’s creators hoped to grow beyond back in 1995. The second time I saw Showgirls was also in a theatrical context, only now it was part of the 2015 Maryland Film Festival’s revival series, and the venue was the Walters Art Gallery. The vibe was like a hoitier and toitier B-Fest, with a pre-show talk extolling the movie’s lack of virtue from three articulately ardent fans, addressed to a crowd that knew full well they were about to see one of the most completely inexplicable would-be blockbusters in recent memory. Which means that I can now award Showgirls yet a third personal superlative: it’s the worst movie I’ve ever seen in revival at an art gallery, too.