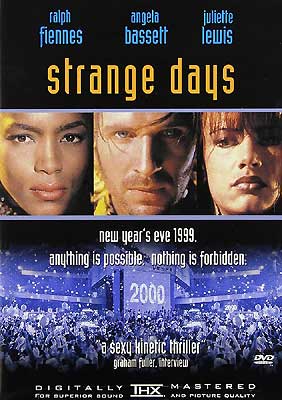

Strange Days (1995) ***

Strange Days (1995) ***

I don’t think it’s just selective memory or preferential nostalgia for the 70’s and 80’s talking. I really do believe that the 1990’s represented, on the whole, something of a historic nadir for the kinds of movies I deal with here at 1000 Misspent Hours and Counting. In that decade, upscale horror films rebranded themselves as suspense pictures to escape the slasher stigma, while their down-market counterparts retreated into jet-black comedy of the splatstick school. Science fiction withered away into a subgenre of action flick, until by the turn of the century, Blockbuster Video took the telling step of merging the two categories on their rental shelves. Softcore sex movies mutated into erotic thrillers, ruthlessly (and hypocritically) punishing the forthright sensuality that they used to celebrate. And genre fantasy virtually ceased to exist, although Sam Raimi did keep it on life support on television from down in New Zealand. Even so, however, the 90’s did produce a share (if not properly their share) of worthwhile fantastic cinema. Hell, a few such movies from those years were even smart. Strange Days, directed by Kathryn Bigelow from a script by James Cameron, is one of those rare films. It’s hampered somewhat by an ending that determinedly ignores the implications of everything leading up to it, and it enjoys the risible distinction of being a cyberpunk movie from 1995 that didn’t see the internet coming, but at a time when most futuristic cinema cared only about bigger and better explosions, Strange Days asks us to think halfway seriously about a whole range of social issues: race relations, police corruption, crime panic, the mechanics of urban blight, and American culture’s burgeoning obsession with vicariousness and voyeurism.

It’s the final week of 1999, and Los Angeles is counting down to a much more serious explosion than the forthcoming fireworks display. Crime has reached levels competitive with Manhattan’s darkest days at the turn of the 80’s, and the LAPD has responded by transforming itself into something that looks more like an occupying army than any conventional law-enforcement organization. (Younger viewers may not recognize that the latter is supposed to feel horrifyingly dystopian, but in 1995, it was still abnormal for police departments to buy castoff military equipment.) There’s a powerful racial current to the city’s woes, too, with those armored riot cops devoting the bulk of their patrolling efforts to black neighborhoods, while few of the faces behind the plexiglass visors of their bulletproof helmets show any skin tone darker than Nordic white. One of the loudest voices of protest against this state of affairs belongs to rapper Jeriko One (Glenn Plummer, from Saw II and Showgirls)— or at any rate, it did up until recently. Jeriko One was just murdered under extremely murky circumstances, and the mood of the city is such that one false move on the part of the authorities could set in motion a wave of mass violence that would make the Rodney King riots look like a schoolyard tussle over a disputed kickball score.

Lenny Nero (Ralph Fiennes, of Red Dragon and Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire) doesn’t know this yet, but he’s already peripherally involved in the Jeriko One crisis, and he’s only going to get nearer the center as the new year approaches. Nero used to be a police detective, but now he’s a petty criminal instead; no reason for his switching sides is ever clearly stated. His main racket these days is going to require some explanation, although the dynamics of it are similar to those of the drug trade. Sometime circa 1996, the military developed the ultimate training, spying, and interrogation tool, the superconducting quantum interference device— or SQUID for short. SQUIDs are capable of reading and recording the full spectrum of human brainwaves in real time, essentially producing a direct copy of the user’s thoughts and perceptions. The machine can then play them back in such a way that they can be fully re-experienced, not only by the person whose brain originally generated the recorded waves, but by anyone wearing the device’s transceiver. The latter somewhat resembles a high-tech hairnet, and can be worn under a hat or wig just as comfortably and unobtrusively as a modern body mic can be fitted to someone’s clothing. It didn’t take long for some enterprising and unscrupulous person to notice the technology’s potential as an entertainment medium, and to smuggle it out onto the black market. Used more or less as intended, SQUID has revolutionized nostalgia, enabling people to store their memories of significant events for perfect preservation and recall. But more enticing still, it lets its users eavesdrop intracranially on people whose lives are more exciting than theirs. My God, the pornographic possibilities alone are staggering! But with SQUID, you can do anything, be anyone— and all at no direct personal risk. Well, okay— all at next to no direct personal risk. The usual caveats associated with buying illegal goods still apply, and many tapeheads (as SQUID users are known on the street) develop a strong psychological dependency on jacking in. Also, too much playback of other people’s memories understandably tends to fuck with one’s sense of identity. And finally, the signal gain during playback needs to be kept within strict parameters in order to prevent cerebral overload. Anyway, Nero deals in SQUID recordings (or “jack”) of nearly all kinds, sourced from people whom he or his suppliers upstream have paid to do various thrilling or fetishistically appealing things while wired up. The one genre he absolutely refuses to touch is blackjack— memories recorded while the person wearing the transceiver is either killing or dying.

What has any of that to do with Jeriko One, you ask? Well, it all comes down to a girl— or three girls, actually. One of them is Faith (Juliette Lewis, of Cape Fear and From Dusk Till Dawn), Nero’s ex-girlfriend, with whom he remains utterly obsessed. Faith is an alt-rock singer, signed to the independent record label owned by Philo Gant (Michael Wincott, from Curtains and The Crow). Gant matters to Nero because he’s both an obvious psycho and the guy for whom Faith left him, but it also happens that one of the other artists in Gant’s stable was Jeriko One. The second woman tying Nero to the looming battle over the rapper’s death is Lornette “Mace” Mason (Angela Bassett, of Innocent Blood and Critters 4), who grew up in the same ghetto as the dead star, and whose heart is still in the hood even though her ass has long since escaped. Mace makes her living driving one of the rentable armored limos that have been all the rage among LA’s upper crust ever since the city entered its apparent death spiral, which means that she spends a lot of time around people like Philo and Faith. That in turn means that Nero is forever using her access and expertise to facilitate his continued stalking of his ex. Finally, Nero is linked to Jeriko One by Iris (Brigitte Bako, from Replikator and Dark Side), an old friend of Faith’s who works as a call girl. Iris witnessed the rapper’s murder by renegade cops Steckler (Vincent D’Onofrio, of The First Turn-On!! and The Cell) and Engelmann (William Fichtner, from Contact and Equilibrium)— and more importantly, she was jacked in at the time, keeping tabs on Jeriko One for the increasingly paranoid Gant.

One night while Nero is plying his trade, Iris accosts him, freaking out about something she can’t coherently explain. This, of course, is the immediate aftermath of Jeriko One’s murder, but Iris is too rattled to communicate that (not least because Steckler and Engelmann are chasing her), and Lenny is too busy making a sale to listen to her babble. So Iris resumes fleeing after hiding the SQUID disc incriminating the two patrolmen in Nero’s car, on the theory that he’ll both watch it and figure out that it was she who left it for him to find. That plan might even have worked, too, had Lenny not parked illegally. Nero’s car gets towed away, the disc ends up in the city impound yard along with it, and the next time Lenny sees Iris, she’s dead. Worse, whoever committed the crime sees to it that Nero receives a SQUID recording of her ingeniously sadistic demise. That, understandably, gets Nero thinking. In time, he’s able to extract enough retrospective sense from the dead girl’s earlier raving to recognize that she was most likely killed in order to hide something, and by that point, word has gotten out that Jeriko One was slain on the same evening. Next, one of Lenny’s suppliers (Richard Edson, from Howard the Duck and Frankensfish) turns up with his brain baked by his own playback equipment, suggesting that somebody very dangerous is looking into the possibility that whatever Iris saw was also SQUID-recorded. Nero and Mace soon have their own tight escape from the two killer cops, after which Nero’s friend, Max (Tom Sizemore, of The Relic and Red Planet), another ex-policeman who now works security for Philo Gant, warns of a faction within the LAPD seeking to go full Magnum Force on the city’s street criminals and the neighborhoods that produce them. Max further implies that these uniformed vigilantes have sympathizers going all the way up to Commissioner Strickland (Josef Somer, from Dracula’s Widow and The Stepford Wives) himself. And when Lenny finally discovers the disc that Iris tried to give him, Mace begins pressuring him to publicize its contents, whatever the risks to the two of them. There’s one piece of the puzzle that doesn’t fit, however. If the object of the conspiracy Nero and his friends have uncovered is to conceal a scheme to turn Los Angeles into a full-blown police state, then why send Nero that recording of Iris being killed? It’s intimidating, sure, and intimidation is a time-tested way of keeping people’s mouths shut, but that tape of his friend’s murder was the very thing that started Nero snooping around in the first place. Has he misjudged the conspirators’ aims? Or is somebody else with an agenda of their own trying to set him up somehow?

The answers to those questions, and the directions in which the movie takes them, are both the best things about Strange Days as a work of speculative fiction and the source of its biggest frustrations. Nero has indeed drawn a lot of the wrong conclusions and trusted a lot of the wrong people. The real story is simultaneously simpler and more complex than he imagines it to be, in that there is not one conspiracy but several, each with objectives much more venal and short-sighted than he assumes. What Nero takes for a unified effort to plunge Los Angeles into jackbooted tyranny from behind the scenes is really just a variegated bunch of bigots, bastards, crooks, and psychos doing what comes naturally to their ilk, and if the city is doomed, it’s only because most folks can usually be counted upon to be their own worst enemies. There’s a refreshing honesty to that, especially coming from a film made at the height of “X-Files” mania. The trouble is, Strange Days carries the headlong rush toward calamity too far to arrest it as cleanly as it does in the end, and relies for that arrest on a mechanism that it’s already shown to be participating in the rush itself. Even if Steckler and Engelmann don’t represent some lawless cabal within the LAPD, Strange Days reaches its climax with police and civilians alike itching for a riot, and Cameron and Bigelow have given us no reason to imagine that cops in this future won’t protect their own just as instinctively and uncritically as their counterparts in the real world. The goodness or badness of any particular apples aside, the problems we’ve been shown for the last two hours and change are unmistakably systemic. To solve them simply by having Commissioner Strickland refrain from acting like Daryl Gates is thoroughly unconvincing, especially if he’s going to arrive on the scene only after the billy clubs have started swinging.

Still, I have to respect any sci-fi movie from this era that not only aspires to be more than escapist entertainment, but actually invokes one of the things from which its audience would most badly want to escape. I also like the weird narrative untidiness caused by the way SQUID figures into the story. In most futuristic movies that have both a thematic axe to grind and a single imaginary technology or discovery added to an otherwise realistic world, there’s a close connection between the two. Blade Runner deals with the moral implications of artificial intelligence. Contact, The Day the Earth Stood Still, and Solaris all ask, in their respective ways, how human life would be changed by interacting with beings from other worlds. A Clockwork Orange uses the Ludovico Technique to explore, among other things, the legitimate limits of law enforcement. But Strange Days is only secondarily— hell, maybe even tertiarily— about the implications of a storage-and-transfer technology for human memories. Normally, I’d score it as a demerit for a work of science fiction to make so little connection between its fantastical elements and the issues it seeks to explore, but it works here because that very disconnect echoes something important in the story. SQUID is a distraction from the main plot in exactly the same way as Nero’s dependency on the technology is a distraction from living his own life in the here-and-now.

That brings me to another thing I quite like about Strange Days, what a lousy hero Lenny is and what a terrific second banana Mace is. In fact, it’s really better to think of Mace as the hero herself, however we’re numbering the bananas here. This too is a situation that usually redounds to a movie’s discredit, but again Strange Days makes it work because the filmmakers seem to understand what they’re doing with their portrayal of the two characters. Nero has one goal in life— to reclaim his girlfriend from that bastard Gant— and if he can’t achieve it, he’ll settle for spending all his free time obsessively reliving his recorded memories of his and Faith’s years together. Nor can he seriously be said to rise above his small-time selfishness as a result of being thrust into the events of the film. It’s Mace who devises the plan to recover Iris’s SQUID disc, Mace who correlates its contents with Max’s tales of organized police malfeasance, and Mace who insists on getting the word out to the media. It’s Mace who saves Lenny’s ass at practically every turn, from Gant’s goons, from the crooked police, and from the shadowy killer maneuvering Nero into taking the fall for his ultimate crime. And when shit turns ugly on New Year’s Eve, it’s Mace on the pavement amid a squad of riot cops, taking a brutal beating in the name of truth and justice. There are a couple different ways of looking at this. You could get pissed off that a black woman has been sidelined in what should by rights be her story in favor of a worthless weasel whose sole qualification for protagonist status is that he’s both white and male, and I wouldn’t really be able to dispute that. But in shortchanging Mace (and to a lesser extent Angela Bassett, whose performance so dominates the film that she looks like the star no matter what her position in the credits), Bigelow and Cameron have done something interesting enough to make up for it so far as I’m concerned. They’ve given us a movie that views its hero the way most of us see heroes in real life, from a position at one or more removes from them. Strange Days could have unfolded from Mace’s point of view, and there were plenty of excellent reasons to handle it that way. However, that would have rendered the film significantly more conventional on a different front, reducing it to yet another tale of a courageous outcast taking a principled stand against oppression. How often outside of comedy do we get a movie showing the rise of a hero through the eyes of her loser schmuck friend who’s too self-absorbed to grasp what he’s looking at? I’d have liked to see a version of Strange Days that gave Mace her full due, certainly, but I’m not sure how happy I’d be trading the quirky perspective of the version we actually have to get it.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact