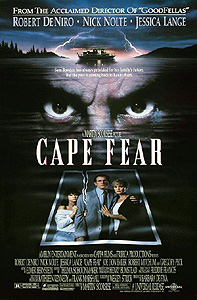

Cape Fear (1991) **

Cape Fear (1991) **

I didn’t expect a whole lot of the original Cape Fear. Sure, I knew what I wanted it to be, and it turned out to be all that and more, but my expectations had been tempered by the disappointment of Night of the Hunter. In contrast, my expectations of Martin Scorsese’s Cape Fear were relatively high, for a combination of reasons. First of all, when it comes to suspense movies on the “horror for people who think they’re too good for horror” model, the style of the early 90’s generally accords more closely with my tastes than that of the early 60’s. Secondly, there was the Taxi Driver connection. Although I have extremely mixed feelings about both Martin Scorsese and Robert De Niro, the last time the latter played a psychopath under the direction of the former, the results were very, very good, and assuming the remake stayed more or less true to the earlier iteration, the basic Cape Fear storyline obviously held the potential for something similarly impressive. And finally, Scorsese’s Cape Fear had developed a reputation as one of the few do-overs to equal if not surpass their predecessors, and it held that reputation among precisely the sort of people who most disdained the staunchly mediocre 90’s version of Diabolique. While I certainly didn’t find it likely that Scorsese had improved on J. Lee Thompson’s masterpiece, I did figure that the newer Cape Fear had to be something pretty special if it could overcome the nearly impregnable critical prejudice against remakes. Alas, however, there’s nothing special at all about Cape Fear. In fact, to return to the subject of expectations, it is exactly the movie one ought to expect when two of the most overrated talents in Hollywood today team up to modernize a film that had almost literally nothing wrong with it.

Mistake number one occurs immediately. The opening credits are followed by voiceover narration from the teenaged Danielle Bowden (Juliette Lewis, of Strange Days and From Dusk Till Dawn), dreamily musing that she was always puzzled by the name, “Cape Fear,” which struck her as completely inappropriate for such a beautiful river. Between the clunky prose and the stilted delivery, it sounds like somebody reading a composition aloud in a high school English class; a similar narrated passage at the end of the film suggests that it’s supposed to be exactly that, but we won’t be getting that hint for more than two hours. In the meantime, it’s nothing but a terrible voiceover, of a sort that was already becoming obsolete when the first film version of this story arrived in theaters.

Next, we’re in the prison cell where Max Cady (De Niro, whose other rare forays into our usual territory include Angel Heart and Brazil) has spent the last fourteen years. The camera pans across a rather incongruous assemblage of law books (later dialogue will imply that Cady owns them, which becomes ridiculous if you know how much a volume of Corpus Juris Secundum or the Federal Supplement cost even in 1991) and photographs of famous villains of world history, finally coming to rest on Cady’s heavily tattooed back as he finishes up his morning exercise routine. This is the day of Cady’s release. When he leaves the prison, he’s naively framed against a sky full of approaching thunderclouds, and he marches right into the camera like Lina Romay in The Bare-Breasted Countess. Scorsese has the good sense to end the shot a split-second before the actual collision, but that’s an inauspicious parallel if ever I saw one.

So who exactly is Danielle Bowden, and what does she have to do with this man getting out of prison in Georgia, two states away? Danielle is the daughter of attorney Sam Bowden (Nick Nolte) and graphic designer Leigh Bowden (Jessica Lange, who fortunately has come a long way since King Kong). Sam used to be a public defender down in Atlanta before he decided that his conscience couldn’t take it anymore, and Max Cady was the man whose heinous crimes led Sam to that decision. In fact, Bowden found Cady’s misdeeds so horrifying that he could not bring himself to do the job he had sworn to, and defend his client to the best of his abilities. He deliberately failed to introduce evidence that the woman Cady was accused of raping and beating had a history of promiscuity, evidence that might have muddied the consent issues in the case sufficiently to win an acquittal. Consequently, when the ex-convict accosts Sam outside his office and makes it clear that he holds him responsible for all those years in prison, he kind of has a point, no matter how much the modern mind revolts at the sleazy tactics that were considered normal and proper in rape trials during the bad old days.

Scorsese and screenwriter Wesley Strick hit most of the same story beats as J. Lee Thompson and James R. Webb had throughout the first and second acts. Cady still shadows the Bowden family all over town, still gets hassled by the cops whenever an excuse arises, still makes ribald comments about Sam’s wife and daughter. There are updated versions of the dog-poisoning incident, the brutal sexual assault on a girl Cady picks up at a bar, the visit Cady pays to the school attended by Bowden’s daughter. Bowden enlists the aid of first the cops, then a private detective, and finally a trio of dock-district thugs before finally being forced to go it alone against his tormentor. This Cape Fear shuffles the order of events considerably, however, and puts drastically different spins on a few key scenes. Cady’s bar pickup is now Lori Davis (Illeana Douglas, from Stir of Echoes), a legal assistant at Bowden’s firm who has a crush on Sam, and with whom he’s maybe a little friendlier than is good for his marriage. The ex-con’s attack on her is thus indirectly an attack on Sam, in a way that the old Cady’s mauling of Diane Taylor was not. Scorsese makes first contact between Max and Danielle not a stalking but a seduction, playing upon the universal assumption of post-60’s teenagers that they know better than their elders. Bowden now watches from hiding as his hired goons work Cady over, meaning that he nearly comes in for his own piece of the retaliation pie when the immensely strong and nearly pain-proof psycho proves more than a match for the whole squad. There’s also a completely new subplot about friction within the Bowden household. Danielle smokes pot, and spent most of the last semester on suspension for doing so on school property. Sam had an affair back in Atlanta, and all those old wounds are reopened when the maiming of Lori Davis brings her friendship with Sam to light on the home front. Leigh’s whole psyche is one seething tangle of resentments, ranging from the amply justified to the nearly delusional. Banding together to face the threat of Max Cady, in other words, is not this family’s instinctive first response.

Oddly, though, it’s the simple reordering of the various plot points that most alters the mood and meaning of the film as compared to its predecessor. The Max Cady played by Robert Mitchum and the Sam Bowden played by Gregory Peck were very evenly matched opponents, and I don’t mean that just in the sense that Peck, like Mitchum, was a big, able-bodied man who looked like he could handle himself in a fist fight. Both antagonists were cool, collected, careful individuals, and each time one of them pushed, the other pushed back with greater but precisely calibrated force. If Bowden spent most of the movie playing right into Cady’s hands, it was because Cady had devoted eight years to thinking about what such a rational, orderly-minded man would do when provoked in various ways. Mitchum’s Cady held the upper hand exactly as long as Bowden continued to do the rational, logical, sensible thing— because “rational,” “logical,” and “sensible” are all synonyms, in practice, for “predictable.” Sam started winning as soon as he stopped doing what “good sense” would dictate. Here, though, Bowden isn’t predictable to begin with. There’s no methodical escalation to the conflict— just Cady provoking and Bowden flailing desperately from one half-cocked reaction to the next. Crucially, the Bowden of the 90’s does not wait until all of his legal options are exhausted before he begins seriously considering extralegal alternatives. Nolte-Bowden resorts much earlier than Peck-Bowden to offering Cady a payoff, for example. When he raises the subject (tellingly, he raises it in terms of the same figures mentioned in 1962, which had lost a lot of their buying power over the intervening decades), Lieutenant Elgart (Mitchum himself, in one of three callbacks to the original Cape Fear cast) is still investigating pretexts on which the stalker might legally be run out of town. The current Bowden also has a peculiar relationship with private detective Claude Kersek (Joe Don Baker, from Joysticks and Mars Attacks!), whose recommendations he is forever second-guessing and whose actions on his behalf he is forever undermining. Bowden thinks before he acts only when planning and analysis are counterproductive to his cause, and the villain scarcely needs his vast physical superiority to ensure that he’s holding all the cards from the word go.

That imbalance between the primary antagonists is part of what makes Scorsese’s Cape Fear so unsatisfying. His version of Bowden might as well be a counselor at Camp Crystal Lake even before the harried family retreats to their river-borne vacation houseboat, and Cady begins exhibiting a tiresome imperviousness to death. The more serious miscalculation, though, is the weakness of character that underlies Sam’s persistent dithering. The old Bowden was a man of principle, and the old Cape Fear more than anything was about how he faced a situation in which principle and expediency alike carried prices too high to pay. The new Bowden is a moral weakling whose principles turn tail and run at the first sign of trouble, whose conscience yammers incessantly, but can never compel. And furthermore, this movie begins with Sam already in the wrong. He violated his professional oath, he cheated on his wife, and he won’t even man up and admit that he’s got a female friend at the office. There’s no drama in forcing a man to compromise his ethics in order to protect his loved ones, when his ethics have never been anything but compromised in the first place.

Cape Fear is also way too heavy-handed not to annoy. An atmospheric night among the mangroves isn’t enough anymore; now the houseboat showdown has to take place in the midst of a thunderstorm-fueled cataract, with the fragile vessel careening out of control between half-submerged stumps and rocks like the focus of a pocket-sized 70’s disaster flick. It isn’t enough for Max Cady to be smart, tough, and ruthless; now he has to have dedicated his time in prison to becoming some sort of pseudo-Nietzschean superman, and he needs Harry Powell’s twisted religiosity and fondness for menacing tattoos (six times as many of them, too!) into the bargain. It isn’t enough for the ordeal a rape victim faces on the witness stand to be grimly invoked as a factor keeping Cady beyond the reach of the law; now it has to be the centerpiece of a soapbox moment that would do any Lifetime Channel original proud. And so on, and so forth, until Danielle’s lumpishly intoned “The… End” on the soundtrack right before the closing credits. What the fuck, Mr. Scorsese? Seriously— what the fuck?

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact