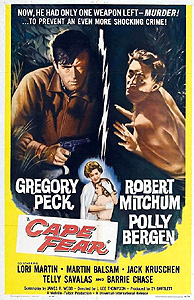

Cape Fear (1962) *****

Cape Fear (1962) *****

Those of you who’ve been reading my reviews for a while might have noticed that I was none too impressed with Night of the Hunter. There is one aspect of that film which I regard extremely highly, however, and that’s Robert Mitchum’s performance as the psychopathic preacher Harry Powell. So perhaps you can imagine how pleased I was when it dawned on me that there was another movie out there in which Mitchum played a Powell-like villain, J. Lee Thompson’s Cape Fear. Now Cape Fear is, if anything, even more universally praised than Night of the Hunter, and that fact led me to approach it with a certain level of caution, but as it happened, no such caution was necessary. Cape Fear is everything the earlier movie was too timid to be, and Mitchum’s character, despite his less flamboyant approach to evil, is even more chilling than Harry Powell.

The man in question is named Max Cady, and he has just recently been released from an eight-year prison term. He had been convicted of rape (and considering that this is Georgia we’re talking about, Cady should thank his lucky stars for his pasty white skin— a black man in his position would surely be dead by now), and the key piece of evidence behind his conviction was the eyewitness testimony of a man named Sam Bowden (Gregory Peck, from On the Beach and The Omen). Bowden, interestingly enough, is a state’s attorney himself, although his role in Cady’s trial was strictly limited to answering another prosecutor’s questions, and it is right after concluding his day’s work at the municipal courthouse that Sam sees the ex-convict for the first time since his turn on the witness stand. Cady stays well within the letter of what both courtesy and the law require, but it is perfectly obvious from his interactions with Bowden that he still harbors a grudge against him for helping to send Max to prison. What’s more, Cady lets Bowden know that this won’t be the last time they meet. He’s actually taken up residence in town, so it’s a safe bet that he and Bowden are going to be crossing paths all over the place. Just what Sam wanted to hear, right?

Cady doesn’t waste any time, either. That very night, he drops in at the bowling alley to shadow Bowden and his family. Sam finds it alarming enough when Cady compliments the attractiveness of his wife, Peggy (Polly Bergen, from Death Cruise and The Haunting of Sarah Hardy), but it isn’t until the stalker shoots a leer in the direction of Bowden’s thirteen-ish daughter, Nancy (Lori Martin), that Sam’s blood really starts running cold. At the earliest opportunity, Bowden goes to see his close friend, Mark Dutton (Martin Balsam, of Psycho and The Sentinel), who happens also to be the local chief of police. Of course, Cady has done nothing illegal as yet, so Dutton has little room to maneuver, but he figures there’s a chance he can run the former rapist out of town on some species of vagrancy charge. No go. As Max will mention later, he passed his time in the cooler reading up on the law, and he has made sure to dot all his I’s and cross all his T’s so as to allow Dutton’s cops no pretext for rousting him. He even smilingly cooperates at every step of the way while Dutton subjects him to what can only be described as a concerted campaign of official harassment, hauling him down to the station to be strip-searched and making a sufficiently visible production of the arrest to cause Cady’s new landlady to cancel their rental agreement. In point of fact, Sam is playing right into Max’s hands by exploiting his ties to the police chief this way, and Dutton is only making things worse for his friend. You see, Cady quickly calls in a fiery young civil rights lawyer named Dave Grafton (Jack Kruschen, from The Angry Red Planet and Satan’s Cheerleaders) to defend him against Dutton’s “persecution” while he stealthily ramps up his operations against the Bowden family. By the time Cady poisons the family dog, Dutton has had to lower the profile substantially in his protection of the Bowdens.

Knowing when he’s been outmaneuvered, Dutton suggests that Bowden employ a private detective. After all, Cady and Grafton can’t raise a stink about favoritism in the deployment of a public resource when Sam is paying for his family’s protection out of his own pocket. The chief even recommends a P.I. he’s worked with on occasion— Charles Sievers (Telly Savalas, from Lisa and the Devil and Horror Express, before he’d acquired his trademark shaven head). Sievers is, in his way, every bit as rough a customer as Cady, and he begins shadowing Max as effectively as Max is shadowing Sam. Indeed, it quickly comes to seem that Sievers has a chance of getting Cady off his client’s back once and for all, for the detective is on the scene when Max picks up an eighteen-year-old drifter named Diane Taylor (Barrie Chase), and brings her back to the flophouse where he’s been staying since his eviction uptown. When Cady beats and rapes Diane, it happens practically in front of Sievers, and he wastes not a second in calling the police. Max must have known he was being watched, however, for he has slipped the scene by the time Dutton’s men arrive, and he has thrown such a terrific scare into his victim that she refuses to testify or press charges, even after Sievers explains to her that she isn’t the only one Cady has been preying upon of late. Round two to Max Cady.

Round three begins when Bowden catches Cady at the local marina, spying on Nancy while she paints the deck fittings on the family boat. When Sam asks Max what he thinks he’s doing, Cady goads the put-upon lawyer into punching him out in front of a crowd of witnesses by making subtly salacious comments about his daughter. Putting that together with Cady’s attack on Diane Taylor convinces Bowden that scruples are a luxury he can no longer afford, and he begins to take the low road. First he tries paying Cady off, but that gets him absolutely nowhere. No amount of money will buy back the eight years Max spent in prison, and he won’t be satisfied until he has inflicted some comparably irreparable harm in exchange. When bribery fails, Sam turns to force, taking Sievers up on an offer to put him in touch with a crew of dockyard thugs who’d be perfectly happy to put Cady in traction for a reasonable fee. So imagine Bowden’s horror when Cady outfights all three of his bully-boys, and then uses the incident to get disbarment and arrest proceedings begun against him! Luckily, Sam still has two aces in the hole. First, he’s got his longstanding friendship with Mark Dutton, who allows himself to be talked into postponing the arrest long enough for Sam to set a trap for his cunning foe, and second, he’s got a houseboat on the Cape Fear River which is perfectly placed to serve as the venue for said trap. Then all he has to do is convince Peggy to volunteer herself and Nancy as bait, and hope that Cady’s lust for revenge will overmaster his nearly diabolical patience if the temptation is great enough.

Now that’s more like it. Though it is, in its way, as much a product of its time as Night of the Hunter, Cape Fear is a far more aggressive and committed film. Director J. Lee Thompson somehow creates the impression that Cady might actually come out on top, even though we know, intellectually, that no such thing is possible in a movie from this era. Most remarkably, that illusion extends even to the possibility of Max raping Nancy, a turn of events that by any realistic assessment would be obviously beyond the bounds of permissibility for a Hollywood suspense film from the early 1960’s. This is a stunning achievement, giving Cape Fear an edge that few if any of its contemporaries can match. The film also benefits from an unusually plausible story, which hinges on precisely the sort of details which all too many suspense and horror movies ignore. Most tales of a criminal mastermind have the villain using his exceptional intelligence to evade the law, but James Webb’s script (adapted from a novel by John D. MacDonald) offers up the nightmare scenario of a vengeance-driven con who has learned how to bend the law to his own ends. Instead of leaving us wondering where the cops are, or how they could be failing to notice what Cady is up to, Webb gives us the answer right up front— they’re gearing up to go after Bowden, who after all is the one who has demonstrably broken the law! The effect is then reinforced by riveting performances from both Gregory Peck and Robert Mitchum. Their meeting at a dockside bar to discuss payoff terms, and Cady’s attendant description of how he dealt with the wife who left him while he was locked up, makes for one of the most powerfully unnerving cinematic conversations I’ve ever witnessed.

Cape Fear also takes on added levels of interest when looked at in the context of later developments on the screen. Though its conclusion might be read as an affirmation of Bowden’s initial faith in the efficacy of law and order, it is ultimately the resourcefulness of Bowden himself that proves decisive. With its central focus thus on drawing Bowden further and further beyond the bounds of his civilized values until the final clash with Cady takes place on almost purely animal terms, Cape Fear can be seen as an early antecedent of the backwoods survival-horror lineage conventionally associated with Deliverance. The difference (apart, obviously, from the setting) is that Cady, while every bit as savage at heart as Papa Jupiter, Madman Mars, or the Leatherface clan, is a civilized savage. Not only can he operate with confidence in polite society, he has educated himself in the intricacies of law so that civilization itself becomes his greatest weapon. Bowden is forced to fight back in the manner of primitive man not because the appurtenances of modernity are irrelevant to the battle, but because they actually give Cady the advantage. To a child of the 80’s such as myself, that theme rings its own set of bells, and from my perspective, the most shocking thing about Cape Fear is how far afield it falls from all the vigilante hero movies of later years. How many films have we seen in which men in Bowden’s position turn their backs on the law and take matters into their own hands when it seems that the authorities are powerless to help them? And how many of those movies seemed to be arguing that we’d all do much better to write the whole “rule of law” thing off as a failed experiment, and just go about our business while packing the hugest available firearm? In Cape Fear, however, it’s obvious that Bowden believes he’s doing the wrong thing when he pulls his strings with the police chief to open the opportunity to trap Cady, even as he recognizes that he has no real alternative. In stark contrast to, say, Death Wish III, this movie has the sophistication to draw a distinction between that which is necessary and that which is laudable. It manages the difficult trick of forcing its heroes into morally objectionable behavior without seriously compromising their status as the heroes or seeming to condone their questionable deeds.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact