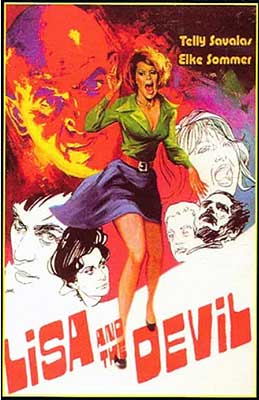

Lisa and the Devil / Lisa e il Diavolo / El Diablo se Lleva los Muertos (1973) ***Ĺ

Lisa and the Devil / Lisa e il Diavolo / El Diablo se Lleva los Muertos (1973) ***Ĺ

Artists who specialize in horroró be they writers, filmmakers, cartoonists, painters, or whateveró have always borne a certain stigma, even at the cyclical heights of the genreís popularity. Itís better now than in the past, probably, but the phenomenon persists if you know what to look for. At the most basic level, it comes down to a question that other creators donít get asked, or at least not with such frequency, or in quite the same disapproving tone: why do you make this stuff? People donít demand that Will Farrell defend making grossout comedies, that Tom Clancy defend writing jingoistic techno-thrillers, or that Thomas Kinkaid defend painting pictures of quaint little houses with a billion candle-powerís worth of light pouring out of their windows, however lowbrow those things might be. They just accept that thatís what those people do. Horror isnít just lowbrow, howeveró itís suspect. And so people continue to ask: why do you make this stuff?

Mario Bavaís answer was manifold. Horror movies made money, for one thing, although they did better overseas than in Italy in his day. And precisely because they were so disreputable, they offered the freedom to do things, to say things, to investigate things that were effectively off-limits in more respectable fields. Meanwhile, fright films let Bava indulge his love for trick photography and special visual effects, which had captured his creative imagination long before he became a director. But most of all, Bava just liked making horror movies. They spoke to him on some very basic level, perhaps because he himself scared so easily.

Nevertheless, by the 1970ís, Bava was beginning to feel cramped by the genre. He wanted to stretch out, to try new things, but his efforts in other areas had mostly not fared well financially, leaving producers reluctant to take him on for anything that didnít involve ghosts, vampires, witches, or psychos. And so he conceived a truly daring project. If he couldnít get backing for non-horror films, then he would just have to push the frontiers of the genre outward until it was roomy enough for him to get comfortable again within it. Lisa and the Devil is the film with which he sought to do that. A strange and elliptical free-form meditation on death, loss, madness, obsession, and inevitability, it truly does bear almost no resemblance to what one generally thinks of as a horror movieó although thereís certainly no other label that fits it any better. Despite clear thematic continuities with the rest of the directorís major works, it feels less like something of his than like a Jesus Franco movie that somehow lucked into a comparatively big budget and a world-class cinematographer. For all practical purposes, itís Mario Bavaís A Virgin Among the Living Dead.

Lisa Reiner (Elke Sommer, from The Astral Factor and Baron Blood) is on vacation with a friend (Kathy Leone, the daughter of producer Alfredo Leone) in some very old yet not at all cosmopolitan Spanish city. While the girls are out sightseeing, they come upon a Medieval fresco depicting the Devil carrying a soul away to Hell. Itís in astonishingly good condition, and the tour guide mentions a local legend asserting that it has been preserved against the ages by the power of Satan himself. Thatís when something provokes Lisa to stick her head into one of the shops they passed earlier, and she darts off, telling her friend to wait for her in the square with the fresco. The shop in question sells antiques of all kinds, and when Lisa comes inside, thereís a customer picking up a wax-faced dummy which heíd sent to be touched up. The man (Telly Savalas, of Faceless and Cape Fear) is friendly and jovial, but he nevertheless frightens Lisa. Partly itís the disturbingly lifelike dummy (which, in a brilliantly eerie trick, is portrayed about half the time by a human actor). Partly itís his intimidating size and strange, orangish complexion. But most of all, heís a dead ringer for the Devil in that old fresco, just as surely as if heíd modeled for it 800 years ago.

Thus begin the weirdest, scariest 24 hours of Lisaís life. The first violation of orderly reality comes the moment she turns to leave the shop, and realizes that the street looks nothing like what she remembers from before she went inside. Thereís no one out walking around, either, despite the busy crowds that were all about her just a few minutes ago. And try as she might, she canít find her way back to the square. Even after the freaksome customer from the antique shopó whose dummy is now more uncannily convincing than everó shows up out of nowhere to give her directions, Lisa just keeps getting more and more lost on streets that seem less and less familiar. Eventually, she reaches what might have been part of the old city wall, where she faces the most unnerving situation yet. A stranger (Espartaco Santoni, from Exorcismís Daughter and The Legend of Blood Castle) approaches her, acting as if he and Lisa were old lovers, but calling her ďElena.Ē The ardent case of mistaken identity would be bad enough by itself, but the man also looks exactly like Antique Shop Devil Guyís dummy! Worse still, in her struggles to get away from him, she trips him down the stairs giving access to the top of the wall, accidentally killing him so far as she can determine. Lisa runs off blindly at that point, no longer caring that she canít tell where sheís going.

Nightfall catches her still out on the streets, just as lost as before. Lisaís about to have company in her misery, however, for Francis Lehar (Eduardo Fajardo, from Hundra and Grave of the Living Dead) is having car trouble. Lehar is out for a drive with his wife, Sophia (Sylvia Koscina, of Judex and The Slasher Is the Sex Maniac), but his antique Packard limousine has sprung a leak in one of its radiator hoses, and thereís nothing on hand that George the chauffeur (Gabriele Tinti, from Black Velvet and Beaks: The Movie) can use to fix it. Luckily for Lisa, the car isnít yet completely incapacitated, so the Lehars are able to offer her a lift when she approaches them while George investigates under the hood. They donít get far, though, before the radiator boils over and the chauffeur announces that any further travel will come at the price of a melted engine. That happens right outside the main gate of a large but dilapidated villa, and the ownerís butler soon comes out to see whatís the matter. Would you believe heís Antique Shop Devil Guy? A moment later, we have a real name by which to call himó Leandroó because one of his bosses arrives on the scene, having apparently been out for a walk in the night air. This is Maximilian (Alessio Orano, of The Killer Must Kill Again and Premarital Experience), son of the countess (Alida Valli, from The Flesh of the Orchid and Suspiria) whose name is on the deed to the old house. Maximilian and his mother argue for a bit over whether or not to invite the stranded travelers to stay a while, but the welcoming Max ultimately prevails over the reclusive countess. Lisa and the Lehars will be spending the night in the guest cottage if it comes to that, however. A suspicious old shut-in has to maintain some principles, after all.

The night at the villa is a harrowing one for everybody. Maximilian turns out to be not exactly sane, and heís more than willing to resort to, say, the murder of the Leharsí driver if thatís what itíll take to make sure he has some damn company around the house for once. Sophia, who had been cheating on Francis for years with George, naturally leaps to the conclusion that the killing was her husbandís work, and flattens him to death with the limo in retaliation. Then she too is killed by Maximilian, apparently because heís decided that the only company he really wants is Lisa. His motives for that are tied to a much stranger peril than any mere killing spree, although the pieces to the puzzle are a long time in falling together. It seems there was once a woman at the villa who looked exactly like Lisa; her name, as you might have guessed, was Elena. Maximilian was in love with her (indeed, he might even have been married to her), but she was in love with Carlos, the countessís second husband and Maximilianís stepfather. Itís hard to say exactly what happened, beyond that neither Elena nor Carlos is alive today to explain it to us. Being dead hasnít stopped Carlos from making a pest of himself around the villa, however, and Lisa has been seeing him off and on since this afternoon. Thatís rightó heís the guy she knocked down the stairs at the city wall. The reason Leandro had a puppet made of him seems to relate to some kind of laying-to-rest ritual in the form of a mock funeral, although itís far from clear whether the object is more mystical or psychological. That is, do Leandro and the countess mean to put Carlosís spirit down for real, or are they staging the exorcism for Maximilianís benefit, so that heíll finally stop believing heís still contending with a dead man for the love of a dead woman? Of course, that in itself may be a moot point, because everything weíre looking at here turns out to be an intrusion of the spirit world into the materialó including even Lisaís very existence as an entity separate from Elena, who like Carlos has been dead much longer than anyone at the villa has let on.

Lisa and the Devil is a rather difficult film, not least because itís a subjective portrayal of reality in collapse. The ďobjectiveĒ story is the one painted in stucco on the side of that building in the squareó the Devil carrying a damned soul away to Helló and its true protagonist is that skeleton in the bridal veil which Maximilian keeps in his bedroom. If Iím reading this movie right, Lisa Reiner never really existed. She is merely the vessel in which Elenaís spirit attempts to escape Satanís clutches. Lisa herself doesnít realize that, however, and what we see here is how she perceives the process of waking up to what she truly is as the Devil catches up to reclaim her. The residents of the villa may be other literal spirits whose fate is bound to Elenaís, or they could equally well be bits of memory resurfacing as Elenaís consciousness emerges from within Lisa. And the Leharsó who knows? Guilty bystanders, perhaps, who become targets of opportunity when their paths and Lisaís intersect? Whatís crucial, though, is that none of that stuff is spelled out for you. Nothing is what it seems on the surface, and the viewer has to work pretty hard to make anything much resembling sense of the picture. It should be obvious by now what Bava meant about enlarging the parameters of the horror film. There are some familiar features here, to be sure: a haunted castle, the ambiguously Mephistophelian Leandro, the Carlos puppet that may or may not be alive, several murders plenty brutal enough to fit the mood of Blood and Black Lace or Twitch of the Death Nerve. But the main locus of horror in Lisa and the Devil is rather the pervasive sense of all existence having slipped its gears.

The subject matter and disjointed, knowingly self-contradictory narrative technique are not the only points on which Lisa and the Devil resembles A Virgin Among the Living Dead. The two films are alike also in their intensely personal natures, and in their refusal to be bound by the crude demands of the market. Neither is entirely successful in drawing the audience into the radically malleable worlds that they create, but both leave the viewer with no doubt that theyíve just come as close as is feasible to spending an hour and a half inside their directorsí heads. What the movies reveal about the terrain inside those heads is strikingly different, however. The motive behind A Virgin Among the Living Dead was therapeutic above all else. Jesus Franco had a fresh trauma in death of Soledad Miranda, and the film was his way of working through that. Lisa and the Devil, on the other hand, is an eruption of stylistic and narrative ideas that Bava had been nursing for years, but had been prevented from using the way he wanted to because they were deemed too weird or too distasteful for a commercial horror film. The 70ís were already shaping up to be a banner decade for weirdness and poor taste, however. Attitudes were changing, censorship was relaxing, and the captains of the cinema industry were reacting to yearsí worth of steadily declining ticket sales by offering unprecedented freedom to any filmmaker who claimed to have something novel and exciting enough to entice people into a theater. If ever there were a moment for a movie about the Devil carrying a dead womanís soul back down to Hell, presented from her perspective as reality falls apart all around her, then 1973 ought to have been it.

Ironically, the trouble was that Bava had done too well. Producer Alfredo Leone had agreed to put up the money for Lisa and the Devil partly because he and Bava were friends, itís true, but the main reason was that Baron Blood had been immensely successful (by Euroschlock standards, anyway) all over the world. That relatively mercenary outlook fell by the wayside, however, when Leone saw the finished product. He didnít just get what Bava was trying to do with Lisa and the Deviló he thought the director had made him a no-fucking-around masterpiece, a film that far transcended the market in which Leone and Bava were used to operating, and which might even enable them to break into the prestigious realm of art cinema. As such, Leone turned down an offer from American International Pictures (which had enjoyed much good fortune with Bavaís films in the past) to buy Lisa and the Devil sight unseen for $375,000 (quite a lot of money in those days for an independent company to pay for an imported horror film without a strong overseas track record), and exhibited it instead on the festival circuit in the hope of attracting big-league distributors. That was a huge mistake. The movie was too arty for the horror crowd, but too horrific for the art crowd, and Leone was able to secure but a single distribution deal, covering Spain and Portugal. (In light of what Iíve been saying about Lisa and the Devil and A Virgin Among the Living Dead, I donít think itís a coincidence that the one place where this movie sold was Jesus Francoís old stomping ground.) Even AIP were no longer interested now that Sam Arkoff understood was he was actually being asked to buy. In the end, audiences outside of Iberia wouldnít see Lisa and the Devil in anything resembling its intended form for ten years, when it began appearing very sporadically on television. That isnít to say, however, that it wasnít seen at alló itís just that thatís another storyÖ

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact