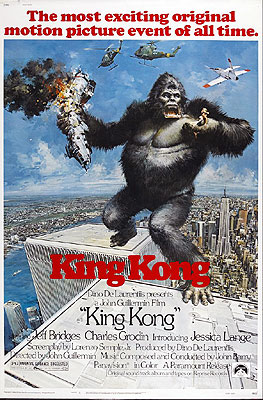

King Kong (1976) -**

King Kong (1976) -**

Dino De Laurentiis has the magic touch, no two ways about it. Not only can he produce worse movies than Sam Arkoff or Roger Corman on budgets that are orders of magnitude greater, he consistently manages to make movies that are worse by corresponding orders of magnitude. You really can almost count on a $25 million De Laurentiis production being roughly a hundred times worse than just about any $250,000 AIP flick. But in my mind, there is one De Laurentiis picture that stands out above all others, and not just because the title monster is the tallest, either. His ill-conceived remake of King Kong is beyond question the greatest fiasco of a career uniquely rich in great fiascos. For those who are too young to have seen the De Laurentiis King Kong in the context of its time, consider this: imagine what might have happened if Battlefield Earth and Gus Van Sant’s inexplicable remake of Psycho had been one film. That would get you somewhere close to the scale of the all-around boondoggle that was the 1976 King Kong.

The trouble with updating King Kong goes beyond the obvious fact that remaking a movie so universally beloved is guaranteed to win you thousands of enemies. The original King Kong was very much a product of its era. The 30’s, being the decade of the Great Depression, were arguably the golden age of the get-rich-quick scheme, and the 19th-century style of showmanship, which produced the circus and sideshow as we know them, was not yet dead. In the context of the time, the idea of a successful but struggling filmmaker convincing an impoverished girl to go with him to parts unknown in search of fame and fortune makes real sense, as does Carl Denham’s decision to capture Kong, rather than simply film him, when the opportunity presents itself. But more importantly, the central conceit of the film— that the giant ape falls into something very much like love with a human woman— is so utterly ridiculous that the movie couldn’t possibly work without the naive innocence of the 1930’s informing its every frame. I could think of a long list of adjectives to describe America in 1976, but “innocent” would be nowhere on it. “Naive,” maybe, but not “innocent.” I suspect that the jokes this movie frequently makes at its own expense were intended as a strategy for getting around this problem. But given that King Kong positively wallows in self-parody even when it’s trying its level best to be serious, this gambit is not a successful one.

So with the Carl Denham-like huckster showman extinct in the world, what possible excuse could there be for bringing a 50-foot gorilla to New York City? I’m not too sure either, but I’ll tell you this: I sure as hell wouldn’t press an oil prospecting expedition into service as my monkey-hauling plot device! I didn’t write the script, though, so oil prospectors it shall be. Fred Wilson (Charles Grodin, from Rosemary’s Baby, who also helped Ishtar bomb expensively eleven years after King Kong) is an executive from the Petrox Corporation. (Those who weren’t around for the mid-70’s may not realize that this is a pun— ask one of your elders about the “pet rocks” fad sometime.) With the decade’s great oil crisis in full swing, Wilson’s company is desperate to find new sources of petroleum that are not controlled by Arabs. So when a U.S. government reconnaissance satellite photographs what looks to be an uncharted island in the South Pacific— an island whose images on the satellite’s infrared and spectrographic film strongly suggest that it is sitting atop an enormous reservoir of oil— Wilson jumps at the chance to take the Petrox Explorer research ship on a little cruise. Wilson has some unwanted company, though. Dr. Jack Prescott (Tron’s Jeff Bridges), a Harvard paleontologist specializing in primates, has stowed away onboard. Prescott has figured out where Wilson is going (it’s really not worth it to ask how), and for reasons that also don’t bear explaining, he believes that island to be inhabited by both human beings and an as-yet-undescribed species of great ape. And because he’s also a long-haired, quasi-hippy tree-hugger (okay, monkey-hugger), he hopes to stop Wilson and Petrox from establishing a drilling operation on the island.

Wilson initially figures Prescott for a corporate spy from a rival oil company, and he orders him locked up while he and the crew run an identity check on him. On the way to his confinement, Jack spots a small rubber raft adrift on the sea off the Petrox Explorer’s port bow. Closer examination reveals this raft to contain an unconscious blonde woman (Jessica Lange, later of Martin Scorsese’s Cape Fear remake) in a black evening gown that reveals absolutely the maximum amount of cleavage and side-swell that it is possible to get away with on a PG rating. The crew brings her aboard, and after much discussion about whether it will be necessary to undress her to look for injuries (pigs), Wilson and Captain Ross (John Randolph, from Conquest of the Planet of the Apes and Earthquake) kick all the men out of the woman’s cabin, and send for Jack Prescott. Prescott, apparently, had a brief flirtation with medical school before going into paleontology, and thus he is the closest thing to a doctor the ship has. (Considering that Jack’s “treatment” of the new passenger extends no farther than an application of smelling salts, it’s probably a good thing he dropped out of med school...) When the woman comes to, most of the audience is likely to wish she hadn’t. Her name is Dwan, and no, that isn’t a typo. As she explains, she was born Dawn, but later switched the letters “to make it more memorable.” That alone should tell you the most important thing about Dwan’s character— she is incredibly, contemptibly stupid. She’s also vapid in a way that only blondes in horrendously overpriced Hollywood movies can be. Naturally, she wants to be a movie star, and it was this that got her into trouble. She was out on the yacht of some asshole who claimed he was a movie producer, and had climbed up on deck when the “producer” and his buddies started watching Deep Throat on their— what? Surely not a VCR in 1976? Super-8 machine, maybe? Anyway, while her date was watching Linda Lovelace going down, Dwan managed to get herself swept off the boat by a big-ass wave, just in time to be safely outside the blast radius when the yacht subsequently exploded for no readily apparent reason. All of which is really just a roundabout way of saying that Dwan, like Prescott, is Wilson’s problem now.

Obviously, she manages to charm her way into coming along when the Petrox Explorer makes landfall, and thus she is there to impress the natives when at last we meet them. The first indication that the island is inhabited is the gigantic wooden wall that the landing party finds stretched across the landscape. Wilson calls it an ancient ruin, but Prescott observes that the wall has clearly been maintained, as the monsoon rains would have destroyed it in just a few years otherwise, and sure enough, he’s right. No sooner has Wilson finished telling Jack he’s out of his mind than the sound of drums comes rolling up from a village two or three valleys away, and Wilson and company rush over to investigate. What they find is an updated version of the “Marriage of Kong” ceremony from the original version, with lower production values and more pelvic thrusting. The shaman stops the show when he spots the outsiders, and makes the familiar offer to trade six of his tribe’s women for Dwan. For some strange reason, Wilson and Prescott don’t see that this is their golden opportunity to get rid of the dizzy bitch, while picking up an entire harem of cute island girls into the bargain, and they refuse the trade, heading back to the ship after a tense standoff. But of course, the islanders sneak up on the ship that night, kidnapping Dwan scant moments after she and Prescott had decided to postpone his planned late-night camera hunt on the island until they were finished fucking. Jack alerts the crew to her abduction, and what passes for the action finally begins.

Man, this movie blows. In the 1933 King Kong, the islanders’ capture of Anne Darrow led to 30 solid minutes of chases, dinosaur fights, and monster rampages, all realized by Willis O’Brien’s groundbreaking stop-motion animation and some of the best image-compositing work in cinema history. This version, on the other hand, gives us a man in a gorilla suit. Okay, so it’s a Rick Baker gorilla suit, and Baker’s gorilla suits have always been the finest in the world, but it’s still a goddamned gorilla suit, and at no point is that ever not obvious! And the incredibly exciting pursuit of Kong through the jungle has been truncated to two incredibly lame set-pieces: the log-bridge scene, and a battle between Kong and one of the worst rubber snakes ever built by a professional special effects crew. These two scenes show up the technical deficiencies of the Di Laurentiis King Kong like nothing else does. In the log scene, the effects team mainly shows the three elements of the action— Kong, the men on the log, and Prescott taking cover in the crevice on the cliff-face a few yards below— individually, rather than go through the effort expended by O’Brien 43 years before, and present all three in a single amazing shot. The snake fight scene is this King Kong’s surrogate for all of O’Brien’s awe-inspiring monster battles, and falls even flatter than the log scene. The snake itself is outright embarrassing; I bought equally convincing rubber snakes from the Kresgie’s toy department when I was eight years old. And what’s more, the interaction between it and Kong is in the vein of Bela Lugosi’s climactic grapple with the octopus in Bride of the Monster. Rick Baker (inside the monkey suit) just holds onto the snake and waves it around, pretending to struggle with it!

So with scarcely any monster action going on, what do the filmmakers give us instead during this phase of the movie? Fucking love scenes between Dwan and the ape, that’s what!!!! These go on forever, and feature some unbelievably bad dialogue. Here’s one particularly stellar example, as Dwan confronts her giant captor for the first time:

“You goddamn chauvinist pig ape! You wanna eat me?! Then go ahead and eat me! Eat me!!!! Choke on me!!!!” Dwan screams, as she whacks Kong on the nose and upper lip with all the strength her scrawny little arms can muster. Then suddenly, it sinks in what an incredibly bad idea this outburst probably is, and she changes her tune.

“Oh, wait... I didn’t mean that, honest I didn’t. Sometimes I get too physical. It’s a sign of insecurity, you know? Like when you knock over trees. Nice ape. Nice, sweet, sweet monkey... You and I are gonna be great friends, I can tell. I’m a Libra— what sign are you? No, don’t tell me... I bet you’re an Aries, aren’t you? Oh, that’s wonderful...”

I hasten to remind you that this is a woman who would go on to win Oscars.

Sooner or later, though, Jack catches up to Kong, and sneaks off with Dwan while the ape is busy with that shitty snake. Meanwhile, back at the wall, Wilson has been informed by his pet scientist that the oil on the island isn’t done “cooking” yet, and won’t be commercially usable for at least 10,000 years. So it’s a good thing Wilson already sent that message back to Petrox trumpeting that he was “bringing back the big one,” huh? With no oil to show for his troubles (or for the lives of most of his men), Wilson tries to salvage the situation by bringing back Kong instead, on the theory that the giant ape will be of use as part of an advertising campaign. Yeah. Sure. Whatever. A few days and two dozen barrels of chloroform later (and note, while we’re at it, that the islanders are entirely, inexplicably absent from this desultory version of Kong’s attack on the Great Wall), Kong is locked in the hold of a Petrox tanker, making sail for New York City.

The exhibition of Kong in this version must simply be seen to be believed. Wilson has set up a sort of arena, in which a replica of the islanders’ altar to Kong has been constructed. Dwan is led up onto the altar while Wilson, in a ridiculous 19th century hunter getup, intones about beauty being lashed to the altar of the beast. Really getting into it now, Wilson extols his audience to “Hail the power... Hail the superpower! Hail the power... of Kong— and Petrox!!!!” and a great big curtain at the far end of the arena parts to reveal... an enormous gas pump. Yes, you read that right— an enormous gas pump. The pump rolls forward on rails set into the pavement until it is scant yards from the altar, and then it too splits open, finally giving the audience a look at Kong, shackled and caged, and wearing a huge, crappy gold crown on his head. Ugh. The altar is soon thronged with paparazzi, who begin manhandling Dwan into an assortment of poses, and Kong goes berserk (apeshit, perhaps?), smashing the “escape-proof” cage, breaking his shackles, and tearing down as much of the arena as he can. Then, just for good measure, he steps on Wilson before running off in pursuit of Dwan.

Again, the movie follows the basic outline of the original, as the ape makes his way across the city, destroying trains and causing a general panic. There’s an amusing moment in which Dwan and Jack try to reassure each other that they’re safe now that they’ve put a river between themselves and Kong, saying that all the bridges have been mined, and apes don’t swim. What makes this so funny is that an ape doesn’t have to swim when he’s taller than the river he wants to cross is deep, and Kong wades right under the mined and guarded bridge without attracting any notice at all. (He also avoids notice at one point by scrunching up into a corner made by two buildings as a police helicopter flies by. This is only one of a great many moments in which I honestly can’t tell whether the filmmakers are joking, or just stupid.) Eventually, Jack notices that the twin towers of the World Trade Center (as new in 1976 as the Empire State Building was in 1933) bear a marked resemblance to a chintzy model set from the island which was one of the ape’s favorite hangouts, and he makes a phone call to the mayor from a hastily evacuated high-priced bar. Jack tells the mayor (50’s monster movie regular John Agar, from Tarantula and The Brain from Planet Arous) that he knows where Kong is going, and will volunteer this information in exchange for the mayor’s guarantee that the monster will be captured alive. They mayor agrees to Prescott’s terms, but the moment he gets off the phone with the scientist, he calls the nearest army base to secure the use of a flight of helicopter gunships. (Never trust a politician…) Meanwhile, Kong has traced Dwan to the bar (don’t ask me how), and while Jack is on the horn with Mayor Doubledealer, Kong reaches in the door and grabs her. Moments later, we’re up on top of the World Trade Center, and Kong is being shot to pieces by the helicopters, despite Dwan’s best efforts to act as the giant gorilla’s human shield. And if you can figure out how Dwan gets down from the roof as fast as she does to weep over Kong’s body, I’d love to hear from you.

There is no form of failure in the world more impressive than failed megalomania. And failed megalomania is very much the name of the game with King Kong. Its most eye-catching failures are, of course, technical. With all the money De Laurentiis spent on this movie, and with Rick Baker handling the special effects, you’d think this King Kong could at least equal the original for visual dazzle. It’s impossible not to ask, while looking at the terrible blue-screen work or the tacky styrofoam and papier-mâché sets, “where did all that money go?!” Would you believe into a life-sized robot Kong? Here’s some of that megalomania I’m talking about. Somehow, Dino De Laurentiis got it into his head that the way to one-up Willis O’Brien was to build a full-scale mechanical model of the giant ape. (Maybe he’d watched Toho’s King Kong Escapes a few too many times.) Well guess what— it didn’t work, and came out looking so screamingly phony that it could be used only for a couple of one- and two-second shots during the scene in which Kong escapes from his cage. And even here, it would probably have been better not to bother at all, as the gargantuan machine is hilariously awful even when seen so fleetingly as that. This useless robot probably cost as much as the entire 1933 King Kong (covering the stupid thing with fur entailed buying up literally all the black horse hair on the worldwide market at the time, for example), and all of that money was thus completely wasted. With Mechanikong sucking up the budget this way, there was simply nothing left over for sets and props and good optical effects, especially after the not-exactly-cheap Rick Baker was called in to make the production-saving gorilla suit.

But more important than the movie’s many technical problems are its myriad artistic woes. Let’s begin with the acting. Jeff Bridges does an okay job with what little he has to work with, but Charles Grodin is terrible, and Jessica Lange is even worse. Then, there’s John Guillermin’s stunningly incompetent direction, which moves the story along at such a ponderous pace that the film clocks in at an inexcusably bloated 135 minutes, fully 35 minutes longer than the original. Finally, there’s Lorenzo Semple Jr.’s script, which yanks crudely at the audience’s heartstrings for more than two hours without ever generating a single moment of authentic emotion. Semple tries to make his Kong the movie’s tragic hero in much the same way that the monster in the 1933 version was, but his efforts to do so by turning the strange connection between the giant ape and a human woman into a full-blown, reciprocal romance produce nothing but rolling eyes and outbursts of incredulous scoffing. When the story has carried Kong to the top of the World Trade Center and we still don’t really give much of a shit about him, there is nothing left to do but pile on the gore in his death scene in a last, desperate attempt to elicit viewer sympathy. But even here, the filmmakers miscalculate, and raise the Grand Guignol excess of the scene to Monty Python, King-Arthur-vs.-the-Black-Knight levels. Even the mostly unfunny jokes that litter the film (probably as a sort of insurance policy— the perpetrators can always point to them and say that the movie was never meant to be taken seriously) can’t save King Kong from itself, because it is never so funny on purpose as it is by accident, and it is rarely funny enough by accident to be worth bothering with.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact