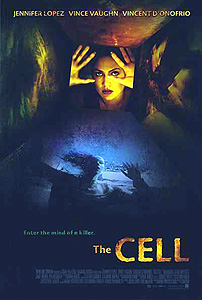

The Cell (2000) **˝

The Cell (2000) **˝

I’m going to have to do a lot more research (which is to say, I’m going to have to watch a lot more movies) before I’ll consider this anything more than a hypothesis, but right now, it seems plausible to me that The Cell represents the emergence of the “torture porn” school of horror typified by the Saw series. Like those much reviled films, The Cell has an inventive psychopath, an endangered captive, and a certain focus on traps and brainwashing, although the unusual nature of its premise is such that they all take rather different forms than would be seen in the genre’s (dare I say it?) more mature entries. The Cell also prefigures 21st-century torture porn in the sense that it is among the earliest films I’ve seen to build upon and extrapolate from the meticulously stylized squalor of Seven. But all things considered, the film’s intrinsic credentials for retrospective inclusion in the genre may be less important than the reaction that greeted its release. I remember very clearly that interspersed with the justly rather effusive praise of The Cell’s imagery, cinematography, and production design was a great deal of hand-wringing over the film’s perceived exultation in brutality, much as would figure in the reviews of Saw, Hostel, and the rest in years to come.

A woman in an impractical, feathery get-up (Anaconda’s Jennifer Lopez) walks through a sandy desert under the sort of vivid blue sky that nature achieves in most climes on only a few days at the apex of Spring. Eventually, she comes upon a small boy (Colton James, of Monster Makers and The Lost World: Jurassic Park) whom she engages in a conversation that we in the audience are ill-equipped to follow. Both participants keep mentioning a strange name, although they can’t seem to agree on a pronunciation; the woman consistently says “Mocky Lock,” while the boy (who for some reason seems to be more likely to know what he’s talking about— maybe it’s because he isn’t played by Jennifer Lopez) favors “Mokilok.” Gradually, it becomes apparent that this is a dream the boy is having, and that the woman is a real person who is interfering in it somehow. To all appearances, he is a psychiatric patient of some kind, and if so, then it’s likely that she is his shrink. Anyway, no sooner have we sorted all that out than the scene is disrupted by what I take to be this Mokilok/Mocky Lock character, who takes the form of a doppelganger of the boy as he might appear decked out for a gig as a monster on “Buffy the Vampire Slayer.” The woman pokes at a microchip embedded in the skin of her hand, and the desert is replaced by a dimly lit room in which the two dreamers hang suspended by wires from the ceiling, clad in rubbery suits that have no obvious reason for resembling flayed human musculature as much as they do. We now learn that the woman is Catherine Deane, the boy Edward Baines. Edward is in some manner of self-induced coma, and ripping off Dreamscape is the only way that Deane— or, more to the point, her employers, Dr. Mirriam Kent (Marianne Jean-Baptiste) and Dr. Barry Cooperman (Asteroid’s Gerry Becker)— have been able to reach him. They have yet to reach him to the extent of waking his ass up, however, and there’s really nothing but Deane’s say-so to indicate that the whole project isn’t 24-carat bullshit. The experiment’s underwriter (Patrick Bauchau, from Creepers and Emmanuelle IV) has been both trusting and generous thus far (which rather behooves him, seeing as he’s also Edward’s father), but it’s been months now with no externally verifiable results, and he’s just about ready to pull the plug.

Meanwhile, FBI agent Peter Novak (Vince Vaughn, from Gus Van Sant’s Psycho) is closing in on serial killer Carl Stargher (Vincent D’Onofrio, of Strange Days and Men in Black). Stargher has quite the MO. He kidnaps girls, keeps them for approximately 40 hours in a fully automated plexiglass cell in his hidden lair, then drowns them, bleaches their bodies until they look like porcelain dolls, and dumps them for Novak to find after fucking them in ways that suggest a Bangkok engagement of the Jim Rose Circus Side Show. Novak and his men have found what they’re pretty sure is Stargher’s house, and the place is currently being surrounded by a substantial federal SWAT team. The way the detective figures it, Julia Hickson (Tara Subkoff, from Teenage Caveman and Black Circle Boys), the latest girl to find her way into Stargher’s clutches, has maybe a day and a half more to go before her drowning, so this bust is coming just in time. Inevitably, though, it will not be that simple. Yes, the SWAT guys have the right house; yes, Stargher is at home when they smash down the door with their nifty travel-size battering ram; and no, the killer hasn’t seen fit to accelerate his schedule. The trouble is that Stargher’s home and abattoir are in two separate locations, meaning that the arrest isn’t quite the glorious cavalry-to-the-rescue undertaking Novak had in mind. Also, no sooner is Stargher in custody than he suffers the sudden onset of the most blatantly made-up medical condition I’ve heard of in many a moon, and lapses into— that’s right— a coma from which he will surely never emerge. Screenwriter Mark Protosevich dubs this bullshit disease “Whellan’s Infraction,” but “MacGuffin’s Catatonia” would have been a much better name for it.

Oh dear, oh dear— however will Novak learn the location of Stargher’s secret killing box in time to save Julia now that the psycho himself is permanently incommunicado? What? Why yes— that’s brilliant! He can ship Stargher over to that experimental psych laboratory he has no cause to know about, and use Catherine Deane’s expertise to pick the killer’s brain! I’m sure the FBI will have no objections at all to releasing a high-profile suspect into the custody of scientists whose research has yielded no measurable results, and whose funding has just been cut off because the person providing it has decided that they’re nothing but a bunch of snake-oil salesmen. Sadly, we don’t get to see the conversation whereby all that is arranged (probably because to present it would be to confront its impossibility directly); all we get is Novak showing up at the lab and telling Kent and Cooperman what he wants Deane to get out of Stargher. The next thing we know, Stargher is hanging from the ceiling in the dream lab next to Catherine, and we’re all thinking, “Yeah, now that you mention it, it is kind of a shame that Dreamscape never got around to showing us the inside of Tommy Ray Glatman’s head.”

The inside of Carl Stargher’s head looks essentially like a Nine Inch Nails video shot on the set of Jan DeBont’s The Haunting. There are lots of winding, yellowish corridors designed to get you lost as fuck should you decide to go for a walk, together with lots of little rooms full of pointy objects, and most of the latter are occupied by memories of the girls Stargher killed, presented in the doll-like state in which he prefers to recall them. There’s also a fair amount of twisted religious imagery (Deane enters the killer’s mind through the scene of a backwoods baptism ceremony that looks only slightly less traumatic than an interrogation session at Guantanamo Bay) and a group of characters whom Deane will be seeing a lot of in various situations. One of those characters, obviously, is Stargher himself, although he turns up with surprising rarity considering that it’s the inside of his brain we’re touring. Much more important is a young boy (Jake Thomas, of Dinocroc and AI: Artificial Intelligence) whom everyone will recognize at once as Stargher’s inner child. The killer’s father (Gareth Williams) is another major presence, cropping up in a succession of bad memories that presumably combine to explain how Stargher got to be the way he is. But the most significant of all Stargher’s mental tenants has got to be the one who represents his dominant image of himself, who bears an astonishing resemblance to Frank Miller’s version of King Xerxes of Persia, as interpreted for the screen by Zack Snyder. Shah-an-Shah Carl the Extensively Perforated sends a masked, thong-clad female body-builder (no, really) to collect Deane and bring her into his presence the moment he realizes that there’s an uninvited guest in his gray matter, and Catherine aborts the dream-link before anything horrible has a chance to happen, despite the fact that she hasn’t yet managed to obtain the information she came for. As Kent and Cooperman explain to Novak when Deane awakens early, it would be all too easy for her to get caught up in her host’s internal reality, and come to accept it subconsciously as really real; if that were to occur, then Deane would be completely at the mercy of the host mind, and not even Novak needs much prodding to see how that would be very, very bad in a host mind that belongs to a serial killer. Of course, we all know that a danger mentioned is a danger prophesied, right? In that case, we also know more or less what’s going to happen to Deane when she goes back inside Stargher’s mind for another try. That makes rescuing Deane a prerequisite for rescuing Julia, and Novak is the only person handy to undertake such a mission.

It’s hard to see what all the bellyaching was about, at least at first glance. The Cell is by no means an exceptionally violent or gory movie, even by the rather restrictive standards of 2000. However, director Tarsem Singh presents such bloodshed as The Cell possesses with an extraordinary degree of visual stylization, and I’m betting that’s what got the whiners whining when the film was in theaters. If you go through life worrying about movies that “glorify” violence, then I can see how the imagery in this one might give you conniption fits. Singh was primarily a director of music videos, and that background definitely shows in The Cell. He treats every camera set-up as if it were a separate painting, paying enormous attention to color balances, the placement of objects and actors within the frame, relationships between positive and negative space, and the like, and he does so whether the action of the scene is two characters meeting in an imaginary desert or a medical examiner conferring with a detective over the corpse of a murder victim. Rarely have dead or suffering bodies been made to look so abstractly beautiful. The obvious answer to the accusation that this glorifies Stargher’s actions is that the vast majority of the film takes place inside the killer’s mind— of course everything inside Stargher’s mind would look like it ought to have a little brass tag beneath it reading, “Still Life with Dead Girl!” The trouble is that Singh isn’t selective enough. The real-world scenes look just as artificial as the mind-world stuff, so that the transitions from one to the other are less affecting than they should be. Stargher’s inner reality loses some of its power to startle and disturb because it represents an insufficiently clean break from Singh’s rendition of outer reality.

That’s a more serious flaw than it might have been, too, because Singh’s great visual artistry is nearly all the movie has going for it. Logical lapses run rampant, character behavior is always just slightly off-key, and the vast moral weight of what happens at the movie’s climax goes apparently unnoticed by everyone concerned, Singh and Mark Protosevich included. The relationship that develops between Deane and the juvenile elements of Stargher’s personality is maddeningly hackneyed, and the vital point that the put-upon youngster and the scarcely-human giant on the golden throne are in fact the same person is left almost totally unexamined. Perhaps most importantly, considering that she plays the movie’s focal-point character, Jennifer Lopez is just a terrible actress, and it is impossible to accept her as a uniquely talented child psychologist, or as a psychic dream-linker, or indeed as someone possessed of any remarkable qualities at all beyond a pair of famously gravity-exempt buttocks. It really plays up how much damage the “yeah, but we need a star” casting mentality can cause. Simply looking at The Cell, I want to say that this movie should have been a great deal better than it turned out. But the truth is more likely that it should have been a whole lot worse, and that Singh’s painterly eye saved it to the maximum extent that it was capable of being saved.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact