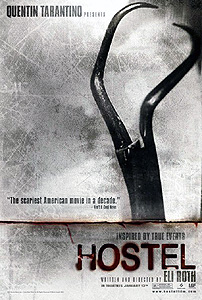

Hostel (2005) -**½

Hostel (2005) -**½

There— you see? Let no one claim that El Santo doesn’t keep his promises. I said I was going to review a normative torture-porn movie one of these days, and now here it is. What’s more, I’m giving you a review of an Eli Roth torture-porn movie, so we’re diving right the fuck in with both feet here. Roth is an interesting figure to me, simply because he manages to have an ongoing career in the first place. People keep giving him money to make movies, and he doesn’t have a German tax loophole to exploit like Uwe Boll did up until recently, so I’m forced to conclude that somebody out there must like his stuff. The thing is, I have yet to encounter a single one of those people. Within the stratum of fandom where I normally operate, “misogynistic asshole” and “talentless cretin” are among the more benign assessments that Roth’s oeuvre has won him. It’s come to the point where I’ve started to think of Eli Roth as the Richard Nixon of modern horror directors— just as the number of people who would still admit to voting for Nixon in the wake of Watergate could not possibly have gotten him elected twice to the presidency, there’s just no way that Quentin Tarantino and Harry Knowles by themselves could account for the $100 million that Cabin Fever took in worldwide. Roth is a lot like the genre he did so much to codify in that sense, for again it’s a case of few defenders, but plenty of ticket sales. Personally, I would love to be one of those defenders, and I don’t even mind embracing the derogatory genre tag that New York Magazine film critic David Edelstein foisted on movies like Saw and Hostel. I mean, really, why shouldn’t I go to bat for these films? If torture-porn signifies anything beyond “horror movies that people my age and up don’t like,” it’s an attempt to bring back the queasy, unsafe quality that the best horror pictures (and even many of the lousy ones) had in the 1970’s. If I’m going to extol the original The Hills Have Eyes for being the only more or less mainstream horror film that I know of to make it seem legitimately possible that the villains would cook and eat a baby, or praise I Spit on Your Grave for forcing me to vicariously experience a brutal gang-rape from the victim’s point of view, then it would be obviously hypocritical of me to wag my finger at Roth and say, “Now, now, Eli— that’s not nice.” So this, then, is why Hostel pisses me off: I came to this movie with an agenda in mind, spoiling to pick a fight in its defense, but the fucking thing isn’t worth the effort. I do think most of the more fevered complaints against it are off-base to one extent or another, but it sucks too much for reasons only tangentially related to the controversies swirling around it to deserve much sticking up for in the controversies themselves.

Paxton (Jay Hernandez, from Joy Ride and Quarantine) and Josh (Reeker’s Derek Richardson) are two American college boys on a summer backpacking tour of Europe. They’re also as intolerable a pair of douchebags as you’re ever likely to meet. As they train-hop from city to city across France, Switzerland, and the Low Countries, they exhibit no interest whatsoever in the history or heritage of the ancient cultural centers they visit; they’re just out to bang as many girls as they can possibly manage. Oh— and they’re also very much interested in the legal marijuana to be had in the Netherlands. We catch up to the lads in Amsterdam, where they have recently befriended Oli (Eythor Gudjonsson), a rather older Icelandic backpacker even randier and more uncouth than themselves. We follow this trio from hash bar to disco to whorehouse, disliking them more with each second we spend in their company, until finally they’ve stayed out past lock-up time at the hostel where they’re all boarding. Oli and Paxton try various means of gaining after-hours ingress (in the course of which the latter diverges just slightly from the Ugly American stereotype— turns out he speaks German pretty fluently), but succeed only in infuriating the neighbors. Just when it seems that the obnoxious tourists are about to get into real trouble, an English-speaking voice calls out to summon them to a window across the street. The owner of that voice is a Russian (Lubomir Bukovy) about intermediate between the boys’ age and Oli’s, and he invites them all to stay the night at his apartment. This helpful young man is named Aleksei, by the way. In between bong hits, the conversation turns to Aleksei’s own backpacking experiences, and the Russian spins his guests a tale of the post-adolescent skirt-chaser’s El Dorado. In Slovakia, in a small town not too far from Bratislava, there is a hostel that might as well be Aphrodite’s gift to horny travelers. The girls there are uniformly gorgeous (they are Slavs, after all), and they’ve got a major thing for foreigners— Americans especially. And because of the war, there’s a distinct shortage of young men in the area, so de facto sex tourists like Oli, Josh, and Paxton have little to fear from local competition. (This business about a war is curious. Unless you count the Soviet occupation of Czechoslovakia in 1968— which met no serious resistance— there has been no military conflict on Slovakian soil since 1945, and Slovakia’s total commitment to NATO operations in Iraq and Afghanistan was something like 300 men in 2005. For reasons I’ll go into later, it’s difficult to guess whether Aleksei is supposed to be gambling on his guests’ ignorance of the world east of the line between Berlin and Trieste, or whether Eli Roth really didn’t know the difference between Slovakia and Bosnia-Hercegovina.) It might sound like a crock of shit, but Aleksei’s digital camera is loaded with photographs that seem to substantiate his story. Before the night is over, Paxton, Josh, and Oli have bagged their plans to move along to Barcelona, and the next morning finds them train-bound for Bratislava.

The trio have an odd encounter on the journey east. Somewhere in what I take to be Austria, a middle-aged Dutch businessman (Jan Vlasák, of The Pool and Normal) takes the fourth seat in their compartment. Almost at once, the Dutchman unwraps some sort of cold-cut-laden salad, and begins to eat it without recourse to utensils of any kind. Upon noticing the bemused looks on the faces of his cabin-mates, he explains that modern people have lost touch with the cycle of life, and that he eschews silverware as a means of creating a more personal connection with his food. If something is going to give up its life for him, he figures the least he can do is to honor it by putting as little distance as possible between himself and that sacrifice. Paxton disgustedly replies that he’s a vegetarian, which is totally beside the point when you think about it— the peppers, onions, and mushrooms in his veggie omelet, or whatever he had for breakfast this morning, used to be alive, but they’re just as dead now as the pigs and turkeys whose flesh garnishes the Dutchman’s salad. Josh gets even more disgusted a moment later, when “Edward Saladhands” lays a hand on his knee in an inappropriately intimate manner. The backpackers have themselves a big, loud, homophobic freak-out, and the businessman retreats to some other compartment for the remainder of the train ride.

Arrival in Bratislava is an occasion for much culture shock. The pollution and infrastructure decay make a stark contrast with scrupulously clean and well-maintained Amsterdam, and the Stalinist architecture that still dominates the downtown is as oppressive as the regime that it was designed to symbolize. Street crime is frighteningly common, with the worst perpetrators being gangs of impoverished children who will literally stab you for a stick of chewing gum. The toothless, sickly-looking cabby who gives them a lift out of the city toward their true destination gives every appearance of being out of his goddamned mind, and his dilapidated vehicle would be more at home in Khartoum or Mombasa than in a European capital. One needn’t be as finicky a traveler as Josh to wonder if maybe this wasn’t such a good idea. Things start looking up once they get to the village, though. The neighborhood where the fabled hostel is situated is actually quite charming, and the hostel itself is lovely. One gets the impression that it had been the home of a wealthy merchant back in pre-Communist days, and while it is undeniably a little faded and shabby now, there is still no mistaking the place’s underlying nature as a classy and genteel edifice. The hostel is very well equipped, too— there’s even a spa in the basement, with hot tubs and steam baths and the whole nine yards. The Americans are initially dismayed when Vala the desk clerk (Jana Havlickova) informs them that they’re going to have roommates, but they change their tune right quick once they meet the people in question. The other occupants of the room Oli reserved turn out to be a couple of phenomenally beautiful Russian girls by the names of Natalya (Barbara Nedeljakova, otherwise known in the States for a barely visible bit-part in Doom) and Svetlana (Jana Kaderabkova), with whom Oli and the Americans hit it off immediately.

This is a horror movie, though, so we know the situation at the hostel has to be a great deal less benign than it appears. What the sex-addled backpackers don’t realize is that their hostel is really the front for an ambitiously evil business venture by the Russian mafia, and that Vala, Natalya, and Svetlana are the well-paid bait in a deadly trap. While low-ranking mob agents like Aleksei lure in gullible foreigners with promises of Slovakian bacchanalia, more established gangsters sell the privilege of killing the trusting fools to a worldwide underground of well-heeled psychopaths— well-heeled psychopaths like that Dutch businessman on the train, for example. That spiel of his about wanting to establish a connection with the things that die for him just took on a whole new meaning, didn’t it?

I don’t think I’ve ever seen a non-made-for-TV movie with more sharply delineated act-breaks than those in Hostel. It’s a matter of tone, really. The first act, in which Paxton and his buddies follow their peckers across Europe, eventually falling in with the Russian mob girls, is boring and sleazy. The second act, in which Oli and Josh go unaccountably missing right after the girls contrive to get their employers’ prey into mutual isolation, and which concludes with Paxton in the death-merchants’ clutches, presents tantalizing hints of the movie Hostel could have been in the hands of a more thoughtful writer or a more discerning director. The third act, in which Paxton gets free of his would-be slayer (thanks to a fatal cascade of accidents so ludicrous that even the Final Destination writers might turn up their noses at it) and launches a counterattack worthy of an early-80’s Death Wish rip-off, is an absolute laugh-riot. It is only during the last half-hour or so that Hostel becomes really entertaining, and the great paradox of this movie is that its intermittently successful midsection is ultimately much less interesting than the relationship between the drastically divergent forms of failure on display at either end.

The most basic problem with Hostel is that Eli Roth simply had no idea how obnoxious his protagonists were. While he admits that Paxton and Josh start off being not the most likeable couple of guys, he believes that he made the boys relatable enough that no one in the audience would be actively wishing them harm. Let’s just say that Roth has maxed out his wrong account with that assertion. The American backpackers start off irritating, become loathsome once we get to know them better, then finally pick up enough humanizing touches to become merely contemptible by the time the mob’s customers get a chance to start carving on them. The defect is brought into especially sharp relief at the moment when Josh’s killer removes his surgical mask to reveal himself as the Dutch businessman. On the basis of our two previous meetings with him— first on the train, then again when he pops up in Bratislava to save Josh from the bubblegum gang— I rather liked Edward Saladhands. He’s weird, sure, but in a pleasant, approachable way, like a friend’s crazy uncle. The best I can say for Josh, in contrast, is that he isn’t as big a dick as Paxton, and that his company wouldn’t become exhausting as quickly as Oli’s. There are two workable ways I can think of to handle the eventual confrontation between these characters. Firstly, the scene might play up the charismatic affability of the killer, and have the victim go to his grave unredeemed from the shallow shitlicker we’ve known him as thus far; the killing itself in this case should be handled in some kitschy manner that would put a little distance between the viewer and the awful reality of murder, so as to preserve audience affection for the bad guy. Or instead, Josh could be made the sympathetic one, and his death scene could wallow in the cruelties inflicted upon him. I suspect that the latter was Roth’s intention, but what he actually gave us was in effect a perfectly mishandled compromise between the two techniques. Imagine how differently the final act of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre would play if instead of Sally Hardesty, it were her vile, wheelchair-bound brother whom the cannibal family “invited” to dinner with Grandpa. Or from the opposite direction, imagine how Theater of Blood would suffer if instead of having his hobo army drown Oliver Larding in a wine cask, Edward Lionheart had simply spirited him off to a secure location, and taken him apart with a scalpel and a power drill. I suppose it might be theoretically possible to pull off a scene in which a formerly sympathetic villain forfeits that sympathy by doing something unforgivably monstrous to a character whom the audience previously had reason to hate, but Roth possesses nothing close to the authorial insight or directorial agility that such a set-piece would require.

The interesting question is how Roth could so underestimate the odiousness of the boys at the center of Hostel’s story, and the answer I arrive at seems to explain a great deal about the movie as a whole. Roth has claimed that Hostel was intended at least partly as a critique of American attitudes toward and behavior in foreign lands, and I don’t believe for a moment that this is mere self-serving, after-the-fact justification on his part. I really do think that Roth honestly meant to say something about ignorant jock wankers roaming the Earth with their dicks in one hand and their daddies’ money in the other, and I also think that there is an excellent jet-black satire to be made on that subject using approximately this premise. The reason Hostel isn’t it is that every aspect of Roth’s public persona suggests that he is Paxton, or at least would have been had the opportunity presented itself. Roth thinks that the backpackers are relatable characters because to all outward appearances, he does relate to them. He somehow fails to recognize himself in his own funhouse mirror, however, and that’s why Hostel degenerates into unwitting farce at the end, suddenly and wholeheartedly buying into the very assumptions that it was supposed to be deconstructing. It’s why there’s no telling what to make of the movie’s overheated and under-particularized portrayal of post-Communist Eastern Europe. And it’s also, I think, why Hostel is so widely accused of misogyny, even though the focus throughout is primarily upon young men being brutalized by their male elders.

Hostel has five featured victims and eight featured villains, and both populations skew noticeably male. Paxton, Josh, and Oli we’ve already covered; the other two victims are a pair of Japanese girls (Keiko Seiko and Jennifer Lim) who are also boarding at the mafia hostel. (What the Japanese girls are doing there is unfortunately never addressed. They’re both very withdrawn and seemingly heterosexual, so it hardly seems probable that they were taken in by a spiel like Aleksei’s. Imagining an equal and opposite pitch delivered by a female mob agent is no help, either, because neither one of these girls could go anywhere single males are found without running a gantlet of guys trying to get into their pants as it is.) If we discount the army of Russian mob goons who staff the torture brothel, the baddies include Aleksei, Natalya, and Sveltana, all of whom are merely the cheese on the mousetrap; Vala the desk clerk and a corrupt Bratislava police inspector (Miroslav Táborský, from Revenge of the Rats and Snow White: A Tale of Terror), whose functions are essentially administrative; and three of the brothel’s customers. In addition to Edward Saladhands, the latter are a German (Petr Janis) who apparently has some genuine surgical training, and a completely unhinged American (Rick Hoffman) who embodies an even more dysfunctional exaggeration of the qualities already represented by Paxton and Josh. The first Japanese girl is disposed of quickly and early on, her demise merely hinted at with a shot of a bolt-cutter closing around the second toe of her left foot, and while we are shown a great deal more of the horrors inflicted on her friend, those torments not only pale beside what happens to Josh, but also absorb considerably less screen time than Paxton’s session with the German. In short, the women among the villains are significantly less evil than the men, while the treatment meted out to the protagonists is precisely opposite to the pattern that infamously obtains among slasher movies. Why is it, then, that Hostel feels so sexually regressive? Because Natalya is the only woman in the film who is even slightly developed as a character. It’s a mistake to call Hostel misogynistic, for the only woman-hating on display comes from the American brothel customer, whom we’re plainly supposed to recognize as perhaps the most odious of all the villains. (Incidentally, Roth lets slip the ideal opportunity to make what he claims was his point in the scene where Paxton and the American psycho meet. Paxton finds the other man almost literally nauseating, but crucially, he shows no sign of recognizing that the difference between them is in all too many respects a matter of degree only.) No, this movie’s gender problem is something much more basic: a nearly complete blindness to female personhood. Thus we see again the uncomfortable similarity between Roth and Paxton, for filmmaker and character alike; seem incapable of conceptualizing women except in some instrumental relationship to men. Women in Hostel might embody male sexual fantasies (indeed, they might be paid handsomely to do so); they might be victims for evildoers to torture and slaughter; they might be damsels in distress for the hero to rescue; but at no point are they ever shown to be people with wills, aims, and agendas of their own. And in that respect if no other, Hostel unmistakably is more sexually regressive than any but the most disreputable slasher movie.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact