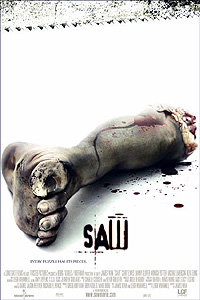

Saw (2004) **½

Saw (2004) **½

If you had asked me in 2004 which movie I thought was going to give rise to the most significant horror franchise of the decade, I’m honestly not sure what I would have said. For one thing, the decade was already half-over, but as yet, there didn’t really seem to be any new horror franchises per se— Final Destination wouldn’t make it to the part 3 mark until 2006, and even then, those movies never developed anything like the vice-grip on the popular imagination that the Friday the 13th and A Nightmare on Elm Street series enjoyed in their day. Nor would I have thought it likely that any of the well-received one-off horror films of the preceding five years were just a savvy marketing angle away from spin-off immortality. Either they had left too little room for continuation (dooming themselves to, at best, a sad succession of dime-budget, in-name-only sequels for the direct-to-video market), or they were remakes living on borrowed buzz in the first place. Of course, I did not see Saw during its initial run of the theaters, but I don’t believe I’d have identified it as the face of big-screen horror in the aughts even if I had. It has a clever premise, competently executed for the most part, but a cascade of critical plausibility failures and an unaccountable lack of emphasis on its most interesting ideas conspire to keep it from looking like anything very special, even when you know about the five sequels it has inspired to date. Then again, who in 1980 would ever have guessed that audiences could be so captivated by a crazy lady carving up teenagers at a New Jersey summer camp?

Unfortunately, the first of those critical plausibility failures occurs in the opening scene, when a young photographer named Adam (Leigh Whannell, of The Matrix Reloaded and Dying Breed) emerges from unconsciousness submerged at the bottom of a bathtub. Subsequent developments suggest that he was drugged before being laid in that tub, and as I don’t see any gills on his neck or an umbilical cord attached to his belly, referee El Santo must regretfully rule one of our protagonists dead before the movie has even properly started. Adam isn’t listening to the ref, however, and he seems little the worse for his immersion-while-unconscious when he struggles out of the tub to find himself in a lightless, echoey room with a stout shackle around his right ankle. (Incidentally, Adam pulls the drain plug with his foot while thrashing around in the tub, and a small object drifts down the pipe unnoticed. This is going to bite him on the ass so fucking hard at the end of the film…) When the lights come on a moment later, Adam sees that his prison is actually the most revolting institutional bathroom this side of CBGB’s, and that he has two cellmates within it. One of these, oncologist Lawrence Gordon (Cary Elwes, from Shadow of the Vampire and The Alphabet Killer), is chained to a pipe like Adam, but at the opposite end of the room. The other is the dead guy lying face-down in a pool of his own blood just beyond the reach of either man’s chain, with a revolver in one hand and a microcassette player in the other. Neither live captive professes to know the other or the dead man, nor does either one have the slightest clue where they are, how they got there, or what any of this is about.

There are clues to the latter mystery on hand, at least. Adam and Lawrence each have an envelope stuffed into one of their pockets; Adam’s contains a tape compatible with the player in the corpse’s hand, while Dr. Gordon’s contains a similar tape, a small key, and a single magnum-load bullet that looks about the right size for the stiff’s pistol. The key does not fit the lock on either man’s shackle, however— that would have been too easy, right? Some creative employment of Adam’s shirt and the drain plug from the tub eventually secures access to the tape player, and the captives get their first solid information about what has befallen them. Adam’s tape is unedifying. An electronically distorted voice offers a dismissive assessment of his character, raises the possibility of him dying in this squalid toilet, and asks him if he intends to let that happen. Gordon’s tape, on the other hand, explains the rules of a deadly game. After a pompous preamble stating that the dead man in the room shot himself because his blood was full of poison, and calling attention to the frequency with which Gordon’s job entails telling people that they don’t have long to live, the recorded voice informs Lawrence that his mission is to kill Adam before 6:00 that evening. A wall clock— the only thing new or clean in the entire room— gives the present time as just a few minutes shy of 10:30 AM, so the doctor has about seven and a half hours in which to decide whether to accept that mission. If he doesn’t, though, or if he fails after taking on the task, then his wife, Alice (Monica Porter, from Along Came a Spider and The Last House on the Left), and daughter, Diana (Makenzie Vega), will die instead, and Lawrence and Adam will both be abandoned to their fate in the locked bathroom. The recording goes on to assure Gordon that everything he’ll need to accomplish his goal can be found somewhere in the room, and concludes with the enigmatic exhortation that X marks the spot.

At this point, Lawrence is pretty sure he knows who their unseen captor is— in the abstract, anyway. If Adam would read a newspaper once in a while, he might have known that the cops in whatever city this is supposed to be have been hunting a serial murderer, whom the press have dubbed the Jigsaw Killer due to his apparent obsession with puzzles. The curious thing about Jigsaw is that so far as anyone knows, he isn’t technically a murderer at all, for his modus operandi is to engineer situations in which his victims are all but compelled to kill themselves, each other, or both. And significantly, he seems to prey specifically on fuck-ups— scammers, wastrels, drug addicts, would-be suicides, and the like. One man was given two hours to find his way out of a cage stuffed with razor wire. Another was injected with slow-acting poison, locked in a room with a safe containing the antidote, and told that the combination was hidden somewhere in the mass of numbers scrawled over every square inch of the interior walls; the catch was that his body was slathered with napalm, and the only light source in the room was a stub of candle. In yet a third case, one victim was immobilized and anesthetized with a massive dose of opiates after being fed the key to a padlock, and another was allowed just a few minutes to extract that key with a scalpel before the head-destroying contraption locked onto her jaws went off. The similarity between those sadistic games and the one Adam and Lawrence are being forced to play is obvious enough, I think. Gordon, by the way, has a bit more insight into the Jigsaw Killer case than the average schmuck, because he was considered a suspect for a while. A penlight with his fingerprints all over it was found at one of the crime scenes about five months ago, and the next morning, two detectives called Tapp (Danny Glover, from Predator 2 and Iceman) and Sing (Ken Leung, of Red Dragon and AI: Artificial Intelligence) picked him up for questioning from the hospital where he works. Lawrence had an alibi, but it wasn’t a story he was exactly eager to tell; he couldn’t have committed the crime because he was busy cheating on his wife at the time. Neither he nor Adam seems to make this connection just now, but the dual targeting of Gordon is itself a clue to their foe’s identity. Granted, infidelity isn’t the kind of thing the Boy Scouts of America hand out merit badges for, but neither does it seem enough to make Gordon a prime Jigsaw Killer target. If Jigsaw nevertheless has it in for Gordon hard enough to attack him twice, then the killer almost has to be someone who knows the doctor personally. A disgruntled coworker, maybe? Or what about a resentful patient? The latter theory would certainly explain that “you tell people they’re going to die every day of your working life” bit from Lawrence’s taped message.

The former theory, meanwhile, would explain what Zep Hindle (Michael Emerson), an orderly from Gordon’s hospital, is doing over at the doctor’s apartment, holding Alice and Diana hostage. On the other hand, although it rarely pays to stereotype in movies like this one, Hindle really doesn’t strike me as a criminal mastermind, and we all know by now to expect a red herring or two. Hindle would fit that bill very well indeed, so the safe money is on him being either an accomplice or just a rogue nut with an agenda of his own. “Rogue nut” would be a pretty good description of Detective Tapp at this point, too. Not long after Gordon’s run-in with him, Tapp came within a hair’s breadth of capturing the Jigsaw Killer, but the bust went calamitously sour. Sing wound up dead, Tapp wound up with a nasty gash through the middle of his larynx, and the latter detective was later pensioned off when it became clear that he had somehow grown fixated on the idea that Gordon was the Jigsaw Killer after all. Tapp now spends all of his time staking out the Gordon place from a ratty apartment across the street, evidently unwilling to accept that the Jigsaw case is no longer his problem. That could come in handy for Alice and Diana, assuming that Tapp still has at least a couple of synapses firing in a remotely sane manner. It doesn’t much help Lawrence and Adam, though, who find that they trust each other less with each passing minute, and who are going to have to come to grips sooner or later with the fact that the surest way out of Jigsaw’s trap is for Gordon to get his hands on that gun and blow his cellmate’s head off.

Man, this is going to be tricky. I really, really don’t want to give away the ending to Saw, but I’ll have to come very close to doing so in order to address the failings that stop it from living up to its potential. Saw’s best feature is that it is as much a puzzle as one of the Jigsaw Killer’s traps, and like one of those traps, it is crucially dependent upon little, easily missed details. Remarkably enough, it truly does play fair with the audience, too, leaving all of its clues sitting right out in the open where anybody paying sufficient attention can find them. The only deception here is the authorial sleight of hand that will likely have most first-time viewers looking in the wrong place whenever those clues surface. For example, there’s a moment early in the flashback to Gordon’s time as a suspect when we’re introduced to two vitally important characters (one of them the killer, in point of fact!), but you’re apt to attach no significance to either one of them at the time because they’re tangential to the action that is nominally the point of the scene. Saw is designed to have you exclaiming, “Oh, shit— that thing!” or, “Oh, shit— that guy!” about every fifteen to twenty minutes, and for the most part it is extraordinarily successful on that level. It’s the kind of movie that can replay the same flashback two or three times, and have it mean something totally different with each retelling.

Where Saw isn’t successful, unfortunately, is in nearly every scene that deals directly with the Jigsaw Killer. This is where we get to the bulk of those critical plausibility failures I mentioned— in fact, it might be simpler to say that Jigsaw is the critical plausibility failure, and that all the individual “Oh, please!” moments that crop up around him are but reflections of the gigantic, multifaceted “Oh, please!” that he himself represents. In order to do what he does, the Jigsaw Killer would need to be a detective, an engineer, a wood- and metalworker, an electrician, an audio-visual technician, a pharmacist, a puppeteer, an acute student of human behavior if not actually a credentialed psychologist, a master of special effects makeup, and above all else the world’s greatest and luckiest location scout. He’d also need to be rich as fuck and able to pay cash for everything, and he’d have to have absolutely no demands on his time other than those related to planning and executing his crimes. And as we discover in Saw’s final scene, he would even require the ability to remain completely motionless for eight hours at a stretch. Next to this guy, Hannibal Lecter looks like a run-of-the-mill cat-burglar— and that’s before we factor in the reversible silk robe and the pig mask! Now there are indeed a few horror movies (The Abominable Dr. Phibes springs immediately to mind) that feature comparably overwrought villains and yet suffer not a bit from having them. Those films all enjoy a couple of advantages that Saw does not, however. When you’ve got a Hannibal Lecter, an Anton Phibes, or a Black Lizard as your villain, you really do need an Anthony Hopkins, a Vincent Price, or an Akihiko Miwa to play him or her. Saw has Tobin Bell, which really isn’t the same thing at all. A baddie like that demands a hell of a lot of screen time, too, but the Jigsaw Killer is but a background presence except during the scene depicting Tapp and Sing’s ill-starred raid on his lair. What’s more, he’s a huge disappointment in that scene, with his labored gait (which mysteriously vanishes when he has to take flight) and his silly hooded robe combining to make him look like an over-the-hill prize fighter limping off to the locker room after a royal ass-kicking. It takes an Olympic-class suspension of disbelief to buy him getting away from the cops on that occasion. But the most serious strike against Jigsaw is the overall tone of Saw. Like so many of the past decade’s horror films, Saw affects a stylized form of squalor derived from David Fincher’s Seven. It isn’t realism, certainly, but the aim is to look and feel nastier-than-real. Jigsaw, in contrast, belongs in an Italian supervillain movie from the 1960’s (think Danger: Diabolik), if not in a Mexican luchador flick. Watch one of the scenes in which he somehow sneaks up on a victim while decked out in his scarlet bathrobe and pig-mask ensemble, and tell me you can’t picture my sweaty and silver-masked namesake racing in to give him a sound thrashing at any moment.

It’s terribly frustrating that the Jigsaw Killer ultimately belongs in some other movie, because there’s one aspect of his character that is perfect for a descendant of Seven, and that would make all the goofy shit worthwhile if only Saw had spent more time on it. Remember that apart from Lawrence Gordon (with whom his beef is implied to be more personal), Jigsaw targets those who are squandering their lives and manufacturing misery for themselves. It turns out that this is because he is terminally ill himself, and it makes him insane with rage when he sees people failing to appreciate what he is soon to lose. I’ve seen an enormous number of movies about killers in my time, and never once can I recall seeing that as a motivation before. It’s the best, smartest idea this movie has, and by all rights it ought to be at the center of everything. It could have been, too, if the focus of Saw’s story had remained on Adam throughout. Instead, though, the filmmakers maddeningly chose to build their story primarily around Gordon, the one victim who doesn’t fit the pattern. This in a movie about a guy who kills people who don’t recognize the value of what they have…

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact