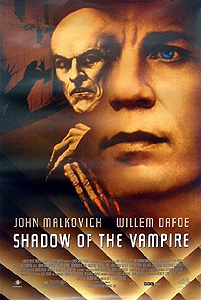

Shadow of the Vampire (2000) ***

Shadow of the Vampire (2000) ***

Of all the actors who have played Count Dracula over the years, only two have ever achieved anything approaching the iconic status of Bela Lugosi’s interpretation. The better known of these two rivals, Christopher Lee, is considered by many to hold just as strong a claim as Lugosi to the title of Definitive Dracula. The Hammer Dracula films with Lee in the title role have vociferous partisans to this day (myself, for example), and Lee certainly made more movies playing the part than Lugosi did. But it is difficult to deny that Lee’s Dracula was built upon the foundation of Lugosi’s, no matter how different the two men’s takes on the character were. The same cannot be said of the third iconic Dracula, however. When Max Schreck took his turn in the role (under the smokescreen name “Count Orlock”) in Nosferatu, his performance owed nothing to anyone, for his was the original screen interpretation. And while no subsequent Dracula has ever followed his lead (except, of course, for Klaus Kinski in Werner Herzog’s direct remake of Nosferatu), Schreck has still been extremely influential. Curt Barlow in Tobe Hooper’s Salem’s Lot; the Master in “Buffy the Vampire Slayer;” Radu in Charles Band’s Subspecies series— all draw upon the Nosferatu model, playing up the monstrosity of the vampire at the expense of his humanity, in much the same way as Schreck had back in 1922. And upon further reflection, perhaps it is only appropriate that the Dracula who dared not speak his name for fear of Florence Stoker’s lawyers should exert his pull most strongly on vampire films that abandon Stoker altogether.

The most remarkable thing about Max Schreck, however, is that unlike Lee and Lugosi, he did not use his sally as the count to build a long and conspicuous career. Schreck was an obscure character actor when F. W. Murnau hired him, and he resumed being an obscure character actor the moment he hung up his fangs. Consequently, the man himself has remained a tantalizing enigma, recognized by millions but known by none. Which means, in turn, that Schreck is an actor whose life is uncommonly easy to fictionalize, on the off chance that somebody should feel themselves moved to do such a thing. As it happens, writer Steven Katz and director Elias Merhige did indeed feel so motivated; the form that their fictionalization took was fiendishly clever, even if it’s also occasionally just a bit too clever for its own good. In Shadow of the Vampire, they postulate that nothing much is known about Max Schreck because he wasn’t really an actor at all, but a genuine vampire, hired by F. W. Murnau as part of an obsessive drive to make Nosferatu as authentic as humanly— or inhumanly— possible.

It’s late in 1921, and director Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau (Mary Reilly’s John Malkovich) has just recently made his fateful decision to adapt Dracula to the screen even without the permission of Bram Stoker’s widow. Shooting has been underway for some time on the studio’s sets, but producer Albin Grau (Udo Kier, from Mark of the Devil and Dr. Jekyll and His Women) still fears that the movie is going to crash and burn before it even makes it to the theaters. For though Murnau has his romantic leads in the form of Gustav von Wangenheim (Eddie Izzard) and Greta Schröder (Catherine McCormack), he still has yet to fill the all-important role of the vampire himself. Murnau tells his producer not to worry. It may be true that no Count Orlock has yet appeared at the studio, but the director has recently concluded an agreement with a mysterious stage actor called Max Schreck (Willem Dafoe, of American Psycho and eXistenZ), who will meet the film crew on location in Czechoslovakia when they head out to shoot the scenes set in the vampire’s castle.

Schreck, or so Murnau warns his colleagues, is what would today be called a method actor, and a bizarrely dedicated one at that. At no point will the rest of the cast and crew ever see him except in full makeup and costume, nor will he ever join them at the village inn where they will all be spending their nights; he’ll be dwelling instead within the crumbling castle throughout the entire shoot. And, of course, all Schreck’s scenes will be shot well after sunset. For all practical purposes, Schreck will cease to exist altogether for the duration of the project, and Count Orlock will take his place. Naturally, this is all just an elaborate cover story, made believable only by the notorious eccentricity of artists in general. The rat-like man who greets Murnau and company at the castle in Czechoslovakia truly is a centuries-old vampire; “Max Schreck” isn’t even his real name, which he has long since forgotten.

You might ask what an ancient vampire could want with an acting career in motion pictures, and even screenwriter Katz would have to admit that’s an extremely good question. The Faustian bargain which Murnau has made with this creature of the night is that, in exchange for his invaluable contribution to Nosferatu’s success, Schreck will be permitted to feed from the cast and crew, so long as he does so discreetly and doesn’t go so far as to kill any of them. Schreck inevitably pushes the terms of the deal to the very limit, however, incapacitating some important members of the crew— including even Murnau’s chief cameraman. And while Murnau is back in Germany recruiting a replacement (Cary Elwes, of The Bride and Bram Stoker’s Dracula), the vampire takes a liking to Greta Schröder; by the time the director has returned, his undead star has decided to raise his price considerably.

Shadow of the Vampire is nothing if not top-heavy with talent. Not only does it have the celebrated Malkovich and Dafoe in the key roles, but even the supporting cast features a number of respected players. Director Elias Merhige, meanwhile, is just about the last man whose name you’d expect to see at the end of the credits in a vampire movie. These are artists— even artistes— we’re dealing with here, and all of them approach Shadow of the Vampire with the utmost seriousness. However, I am of the opinion that it is precisely the presence of all these self-consciously formidable creative types that prevents the movie from fulfilling its potential. Everybody (except maybe Kier, whose early career gives him no excuse for such fusty sentiments) seems somehow uneasy at the prospect of working on what by rights ought to be classed as a horror film. Merhige especially comes across as faintly embarrassed, and he does everything in his power to distance Shadow of the Vampire from its subject matter. It’s as if the only way he could bring himself to make this movie was by convincing himself that it’s really about the suffering and sacrifice that True Art always demands of its creators, and that it only just happens to have a vampire in it. Now certainly that’s a powerful and resonant idea Merhige is playing with, and this particular story lends itself especially well to its exploration. The trouble is, Merhige is not content to let subtext be subtext. He pursues his theme of the price art exacts from the artist at the story’s expense rather than using it to enrich the film like a good subtext should. What makes this doubly unfortunate is that on those rare occasions when Shadow of the Vampire isn’t scrambling to draw your attention away from the V-word, it does some wonderful things with what often seems to be a played-out mythos. For instance, there is a terrific scene that takes place while Murnau is away from the castle set, in which Schreck explains to Grau and another member of the crew just what it was that attracted him to Dracula. In telling them that he found the book terribly sad, the vampire goes on a long tangent about what it must have been like for Dracula to entertain Harker at his castle— after all those centuries of solitary unlife, what a struggle it must have been even to remember how to set a table! Ever since Anne Rice arrived on the scene, vampires have become increasingly mawkish, maudlin, and suffused with self-pity, yet not once in any of the novels or films I’ve been exposed to that followed her lead have I seen anything that so vividly evoked the loneliness and misery of the undead condition. And what’s more, Merhige and Dafoe put the idea across without making Schreck look the slightest bit like a simpering whiner. After all, a guy who looks like a human rodent, who forgot his last social skill 200 years ago, has far more honest grounds for loneliness than the prancing, pretty-boy wankers of Interview with the Vampire! If Merhige had possessed the confidence to deal with the genre on its own terms rather than trying to insulate himself from it with a comforting cushion of Deep Thoughts, Shadow of the Vampire could have been something far more potent than the technically accomplished but only timidly inventive big-budget art film it wound up as.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact