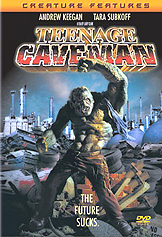

Teenage Caveman (2001) **½

Teenage Caveman (2001) **½

The first time I encountered the Creature Features label, it confused the hell out of me. I mean, love it or hate it, there’s just no getting around the fact that setting up a company for the exclusive purpose of producing made-for-cable, in-name-only remakes of 50’s-vintage AIP films is a strange, strange idea. Who would want to do a thing like turning Earth vs. the Spider into a cheap Spiderman knockoff (okay, so maybe a cheap Venom knockoff is more like it), or re-casting The She-Creature as some kind of weird lesbian mermaid thing? I’ll tell you who— Louis S. Arkoff, son of American International Pictures co-founder Samuel Z. Arkoff. (You do realize what a priceless opportunity the younger Arkoff let slip here, don’t you? Why name your studio something lame like Creature Features when you could have called it “Son of Sam Productions”?!) Teenage Caveman, the most recent Creature Features flick, offers a couple of advantages over its older sisters in that its story actually does flow somewhat logically from the recycled title and to a lesser extent from the original film, while the total package suggests that Lou Arkoff has finally become comfortable with the idea that if you’re going to re-make trash— even obliquely— the best way to go is to make your new version even trashier. On the other hand, the good points are cancelled out to a disappointing extent by the filmmakers’ decision to approach the project as if they were trying to make a Full Moon movie, only sleazier.

The most immediately obvious difference between this Teenage Caveman and the old one is that the 1958 version’s twist ending now makes its appearance at the climax of the pre-credits sequence. A hunting party of spear-wielding teenagers, led by an adult man, is roaming around in the wilderness when an argument breaks out between the adult chaperone and Vincent (Stephen Jasso), one of his young charges. It’s just the usual bullshit, really— the boy thinks he’s bigger and tougher and smarter than he really is, and he resents his elders telling him what to do. But this society is obviously a bit less well-regulated than ours, because the confrontation quickly escalates to the level of lethal physical violence, and Vincent runs the man through with his spear. And when the man falls to the ground, we realize that the shaft of Vincent’s weapon is not made out of a long, straight stick, but rather from a decayed “No Skateboarding” sign! These primitive hunter-gatherers aren’t prehistoric— they’re post-historic!

Yeah, well be that as it may, these kids are still going to be in trouble when they get back to their village if they don’t come up with a good cover story, and fast. Eventually, their de facto leader, David (Andrew Keegan, whose “7th Heaven” producers and cast-mates were surely horrified to see him turn up in a movie like this), persuades his companions that the safest bet is to tell the folks back home that their hunting instructor was attacked and eaten by a “predator.” (The characters in this movie will talk a lot about “predators,” but we never get to see one of the beasts in person.) The story goes over well, but it isn’t long before cause for even more serious intergenerational strife surfaces. You see, David’s father (Paul Hipp, from Bad Channels and Face/Off) is the tribe’s shaman (gotta love the “God is coming and he is pissed” chant that makes up the centerpiece of his shamanic liturgy), and as is his prerogative, he has chosen a young girl from the tribe to serve as his acolyte and bed-mate. The problem here is that Sarah (Tara Subkoff, of Black Circle Boys and The Cell), the girl whom he has selected, happens to be his son’s girlfriend. (“Don’t worry— I’ll share her with you,” he reassures his offspring.) When violence finally breaks out between David and his dad, the confrontation doesn’t go nearly so well for the boy as had Vincent’s face-off with the master hunter. David ends up tied to a tree in his post-apocalyptic skivvies, left to die from exposure, thirst, starvation, or predators, whichever gets to him first.

His friends all think this is a shitty deal, though, and before long, Sarah, Vincent, and three more cave-kids— Elizabeth (Crystal Grant, from Lawnmower Man 2), Joshua (Shan Elliot), and Heather (Hayley Keenan)— sneak out to the Tree of Woe (no one really calls it that, but they damn well ought to) and cut David down. This, of course, makes them outlaws from their tribe, and so as soon as David is recovered from his ordeal, he leads them off into the wilderness in search of an ancient settlement from before the apocalypse, the legendary city of Seattle. But just as the city’s ruined skyline looms up on the horizon, Heather mentions that she feels a storm coming. Yep— that’s a storm, alright. Such a storm, indeed, that it had to be depicted with a CGI effect. There is no shelter around equal to the task of protecting David and company from the tempest’s fury, and all six voyagers are laid low in short order.

The kids are awakened a bit later by the dulcet strains of the Misfits’ “Where Eagles Dare,” piped over an intercom system at brain-hammering volume. They’ve been taken to some kind of swank urban dwelling, and tricked out in various types of fashionable early 21st-century underwear— naturally, they’re all very confused. Then their hosts appear, and at least some of that confusion dissipates. The dwelling is the basement of a long-abandoned biological research institute, which was attached, in pre-apocalyptic times, to some university or other. Neil (Richard Hillman) and his girlfriend, Judith (Tiffany Limos), themselves apparently only slightly older than David and his friends, figured out that it was one of the few places around that the end of the world left untouched, and set up shop there some years ago. Life in the city apparently differs from life out in the sticks just as profoundly in the stone-age future as it does in our own time, and instead of spending all their waking hours hunting and foraging, Neil and Judith have plenty of free time in which to collect pop-culture souvenirs from the vanished civilization of North America, snort prodigious amounts of cocaine, and have crazy monkey sex with anyone and everyone who rolls into town. (It’s probably better not to ask where they’re getting all that coke.) As you might imagine, the lifestyle has its appeal for the exiled cave-teens, or at least for all of them except the inexplicably goody-two-shoes Sarah, who is joined in her abstinence by David, who’ll do pretty much anything his girlfriend says.

And if you’ve watched more than a handful of horror movies, you don’t need me to tell you that Sarah actually has the right idea, counterintuitive as it may seem. For Neil and Judith haven’t been precisely honest with their guests. They didn’t seek out the old lab on the basis of legends and rumors about the city— no, not at all. Nor does their familiarity with pre-apocalyptic culture stem from the haphazard recreational research that their great amounts of leisure time permit them to conduct. No, Neil and Judith got all of their insight into the Old Times first-hand. They were students at the university that operated the lab, and 90 years ago, they volunteered to take part in some kind of biological experiments. Somehow, these experiments turned them into immortal beings with greatly enhanced senses and tremendous psychic abilities, but also rendered them sterile. But though Neil is incapable of getting Judith pregnant, either one of them can “infect” a normal human with whatever bioagent it was that transformed them; all they need to do is fuck you, and you turn into the same sort of creature as them. Or so it should work, at any rate. In practice, most human constitutions are too weak to survive the wholesale physiological changes that come with infection, and Elizabeth, the first of the cave-teens to spread her legs for Neil, explodes into a mass of gelatinous meat the very next morning. Talented bio-students that they are, Neil and Judith think they can figure out a way to make the rest of their breeding stock survive the experience of laying them, but in order to do that, they’ll have to keep David and his friends from learning what happened to Elizabeth. And since Sarah doesn’t seem to trust them to begin with, she’s obviously the one who’ll receive the bulk of their attentions. In fact, if Judith can’t find a way into David’s pants before Sarah discovers what’s really going on, it may just be necessary to kill her outright.

One of the people I watched Teenage Caveman with kept remarking that it seemed to her like a demented hybrid of The Rocky Horror Picture Show and Kids. There’s a very good reason for that, actually. Teenage Caveman and Kids were both directed by the same man, Larry Clark. Clark has a way with sleaze that serves him well here. In his hands, the decadent, anything-that-moves sexuality of Neil and Judith rises above the kitsch effect of their outrageous costumes, the studied tackiness of the sets depicting their home, and Richard Hillman’s preposterous overacting to become simultaneously titillating and grotesque. It’s also tempting to try to read some heavy subtext about venereal disease or hardcore drug abuse or the Baby Boom generation’s abdication of parental responsibility and the dangers it poses for their children into this film, and considering who made it, that really might not be entirely inappropriate. Between its almost (but noticeably not quite) 70’s approach to sex and drugs and generalized perversity, and the sneaking suspicion one gets that there may be a brain hiding in its head after all, Teenage Caveman comes within an ace of being the best shameless exploitation movie of recent years. What stops it from reaching the heights it might have is the unfortunate lack of effort that seems to have been put into circumventing this sort of film’s built-in limiting factor: that modern teenagers, realistically portrayed, make for insufferably obnoxious movie characters. A lot of people bitch about the extent to which the dialogue in most Full Moon movies consists almost entirely of petty bickering between the uniformly youthful central characters, but the depressing fact is that the phenomenon is merely an exaggeration (a fairly extreme one, I grant you) of the way most people I know between the ages of 15 and 21 actually act. Screenwriter Christos N. Gage doesn’t take it as far as the average screenwriter in the employ of Charles Band, but the all-youth cast of Teenage Caveman are definitely made to seem a tiresome, unlikable lot. I also found it annoying that a movie which otherwise exhibits such frankness about debauchery both carnal and pharmacological should suffer from that puzzling 90’s-vintage shyness about frontal nudity. Some of the camera tricks Larry Clark employs to keep his actors’ genitals out of the shot are simply hilarious. As has happened to me so many times when watching a recent made-for-cable/direct-to-video movie, I spent much of Teenage Caveman’s unnecessarily long 95-minute running time (the original’s 65 minutes would have been closer to the mark) grumbling to myself about how much better it could have been had it been made 25 years earlier.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact