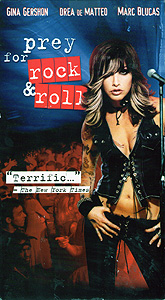

Prey for Rock & Roll (2003) ***

Prey for Rock & Roll (2003) ***

No, I can’t say I’d ever heard of Lovedog, either, and if Prey for Rock & Roll is any indication, that obscurity was a sore point for frontwoman Cheri Lovedog for a good many years. This movie began life as a semi-autobiographical play— performed, strangely enough (and yet somehow not strangely at all), at New York’s ur-punk club, CBGB— presenting scrambled, veiled, and to some extent exaggerated versions of Cheri Lovedog’s experiences in the trenches of the 80’s and 90’s punk scenes. The film version was made with substantial input and involvement from Lovedog herself, incorporates easily an album’s worth of music she wrote either for the play or during her fifteen years as a would-be professional musician, and in general shows very little sign of having been subjected to the usual Hollywood treatment. Consequently, what is most curious about it is the absence of nearly anything that would situate its story specifically within a latter-day punk rock milieu. As a “perils of the rock and roll lifestyle” movie, it is both well made and fairly credible, but were it not for one highly unusual aspect of the film’s apparent moral, it could just as easily have been written about late-60’s acid-trippers, 70’s arena-rock wannabes, or 80’s hair-metal headbangers. In fact, at times it feels almost like an inadvertent remake of David Friedman’s Bummer!, only with the band and their groupies collapsed into a single set of characters.

The central figures in the film are the four women who comprise a Los Angeles-based punk band by the unfortunate (but fortunately seldom-uttered) name of Clam Dandy. Bass-player Tracy (Drea de Matteo, from the 2005 remake of Assault on Precinct 13, reprising her role from the stage play) is a member of that distinctive L.A. breed, the trust-fund punk. She’s also a drunk, a stoner, and a cokehead, faults which balance precariously against her reportedly considerable virtues as a musician. Lead guitarist Faith (Lori Petty, of Tank Girl and Route 666) possesses the highest concentration of technical ability in the group, enough so that she is able to earn her living giving music lessons by day. Drummer Sally (Shelly Cole) is the youngest and least streetwise of the foursome; she’s also Faith’s girlfriend. But the focus of the film throughout is solidly on singer, songwriter, and rhythm guitarist Jacki (Gina Gershon, from Voodoo Dawn and Showgirls). Jacki got bitten early by the rock and roll bug, when the boy she was dating in seventh grade talked his parents into taking them to see Tina Turner. That was probably around 1976. About a year later, the world outside New York, London, and Detroit got wind of this thing called punk rock, and Jacki realized what she was going to have to do with her life. She “headed over the mountain to Los Angeles as soon as [she] got [her] driver’s license,” which put her just in time to witness the glory days of X (the recycling of the X footage from The Decline of Western Civilization, shot in 1980, provides the baseline from which I have extrapolated Jacki’s chronology), then spent the ensuing two decades playing in a succession of all-girl punk bands. None of those groups— up to and including Clam Dandy— ever developed more than a local following, however, leaving Jacki’s itch for rock and roll stardom stubbornly unscratched. As we join the action, it’s two days before Jacki’s 40th birthday, and she’s feeling a mid-life crisis coming on. But whereas most such crises manifest themselves in futile and embarrassing efforts on the sufferers’ parts to regain their lost youth, Jacki’s has more to do with the realization that she never really left her youth behind, no matter how far into the past it receded. With 40 hanging over her head like one of Monty Python’s sixteen-ton weights, Jacki continues to live almost exactly the was she did at twenty, having neither grown up in any way that her mother (Sandra Seacat) or siblings would recognize, nor advanced her musical career more than a few short steps toward those dreams that took hold of her the first time she heard Exene Cervenka singing about her and John Doe’s love passing out on the couch.

With such thoughts taking up most of the space in her skull, it is perhaps understandable how Jacki reacts when the phone rings just a few minutes after she and her girlfriend, Jessica (Shakara Ledard), have squirmed into bed together, and the voice at the other end of the line turns out to be that of Chuck (Eddie Driscoll, from the 1995 version of Not of This Earth), a promoter and A&R man whom she has known for some years. Jessica plausibly expects Jacki to tell Chuck to call her back later, but the promoter’s news is too big and urgent for Jacki to think about anything as “trivial” as romance in the face of it. Chuck has an in with the booking agent responsible for an upcoming X reunion show, and he’s learned that the opening act has had to cancel— something about a drug overdose and a dead drummer. If Jacki is interested, Chuck thinks he might be able to get Clam Dandy on the bill as a replacement. He’d also like to meet with the whole band sometime soon, to discuss the possibility of signing them to the independent record label he represents. Jacki’s interested, alright— so interested, in fact, that it doesn’t really bother her when the disgusted Jessica not only gets dressed to leave, but starts packing up whatever of her stuff has migrated to Jacki’s place over the time that they’ve been dating. Girlfriends come and go, but how often do you get an offer to share a stage with people you’ve idolized since you were sixteen years old?

We all know the formula for stories of this sort, though, don’t we? Increasing professional success must always be counterbalanced by commensurately escalating trouble on the personal front— Newton’s Third Law of Showbiz Movies, I call it. Predictably, a substantial number of those personal troubles come courtesy of Tracy’s rapidly worsening drug and alcohol habits, which also begin jeopardizing the new professional opportunities in which Jacki has placed such heavy emotional investment. Others come instead from the complicating influence of the band-members’ romantic entanglements, or from an eruption of plain, dumb, rotten luck. With Jessica out of the picture, Jacki is as close to available as she is psychologically capable of being, and she finds her heart going in unwanted directions when Sally’s big brother, Animal (Marc Blucas, of They and Three)— newly released from the lengthy prison term that started when he beat his sexually abusive stepfather to death with a baseball bat at the age of sixteen— shows up at the Clam Dandy house looking for a place to crash until he can make more permanent living arrangements. (And for whatever it’s worth, I think I, too, might be persuaded to date in defiance of both my usual preferences and my better judgement, were I offered a heavily tattooed, shaven-headed Marc Blucas.) Meanwhile, Tracy’s way-creepy boyfriend, Nick (Ivan Martin), goes off the deep end after a bid to act out his longstanding rape fantasy in the midst of a coke bender yields results other than those he anticipated, leading to a beating for Tracy, an all-too-real rape for Sally, and a tattoo artist’s version of I Spit on Your Grave for Nick himself. Then Faith gets run over by a car while chasing the teenage pricks who stole her guitar, and the remaining Clam Dandy girls officially hit bottom. Naturally, it’s at just that moment that Chuck’s recording contract arrives in the mail, offering terms far less favorable than what Jacki believes her band (to say nothing of her personal efforts over the last twenty years) deserves.

I won’t say Prey for Rock & Roll rings false, because its semi-autobiographical nature, together with the close collaboration between the filmmakers and Cheri Lovedog, presumably makes it a fair reflection of its author’s experience and understanding of the events that it dramatizes and paraphrases. It certainly does ring odd, however, most particularly as regards Jacki’s reaction to her limited professional success as a musician. Some of what Jacki feels as she looks back on twenty years’ worth of unevenly received rocking and rolling I relate to very strongly. The idea that she’s getting too old for this shit, that at this point she’s merely impersonating her twenty-year-old self, and the nagging suspicion that maybe— just maybe— that makes her pathetic… Well, I’ve got a while to go yet before 40 comes knocking, but I already think about all of those things every time I climb down, sweating and wheezing, from the stage after playing my guts out for a too-tiny crowd with far more interest in the pints of Yuengling on the bar in front of them than in anything my bandmates and I just spent the past 45 minutes doing. But unlike Jacki (or, one gathers, Cheri Lovedog), I never thought for one second during the last eighteen years that I would ever be anybody’s idea of a rock star. Furthermore, I don’t believe any of the literally hundreds of punks, skins, and headbangers I’ve shared stages with over the course of that time did, either. Maybe the temporal context makes all the difference. 1978, when Cheri Lovedog got her start, was the high point of the brief period in which it seemed like punk might prove to be as commercially viable as any of the preceding Hip New Things that had periodically scrabbled up from rock and roll’s cellar, whereas by 1990 (when I got mine), the mainstream music industry had given up even attempting to co-opt punk, let alone make money on the real thing. (Of course, the situation would reverse itself again about five years later, leading to a co-optation more successful than anything the execs at Warner Brothers dreamed of when they bought out Slash Records in order to gain control of X.) Or maybe the issue is simply that I don’t live in Los Angeles, and therefore don’t find myself presented with celebrity as a normal fact of day-to-day life. Either way, my experience has been that people don’t start punk, thrash, oi, or hardcore bands for a shot at fame and fortune. In my experience, the short-timers do it essentially for the thrill of it, while those of us who are in it for the long haul do it because something in our psyches gives us little or no choice in the matter. Prey for Rock & Roll is probably best understood (and most clearly reflects a specifically punk mindset) as the story of how one woman eventually comes to the realization that she is one of those helpless lifers, and recognizes the pursuit of stardom for the snare and delusion that it almost invariably is, but it seems very strange to me that it takes her twenty years to figure it out.

This movie is also an interesting test of the flipside to the theory behind the casting for Penelope Spheeris’s Suburbia. At the time (1983), Spheeris was quoted as saying that she knew she’d never be able to turn actors into punks, so she tried turning punks into actors instead. Prey for Rock & Roll takes the opposite tack, and crucially, it does so even to the extent that the band we hear playing Clam Dandy’s material on the soundtrack really is Gina Gershon, Lori Petty, Drea de Matteo, and Shelly Cole, recorded under conditions intended to approximate the sound of a live band. The actresses are thus required to be convincing not merely as punks, but as punk musicians. In the former endeavor, they are greatly assisted by Lovedog’s insider perspective in the writing, especially as concerns dialogue (a subculture’s slang and speech patterns are almost always the hardest things for outsiders to get right), but the actresses themselves (and Marc Blucas, too) still deserve a lot of credit. With the horribly glaring exception of Faith’s teenaged student (Ashley Eckstein), these are among the most natural-seeming movie punks I can ever remember seeing. Gershon and company acquit themselves well in the concert scenes, too, plausibly capturing the stage mannerisms of a group that has been playing together for a number of years. As for their performance as a band, they come across as tight but unschooled, which is exactly how they ought to sound given the circumstances put forward in the script. Clam Dandy are not supposed to be virtuoso musicians, nor are they supposed to be vastly popular. They’re a hardworking but also hard-luck band with a small hometown following, and it is strongly implied that they’re almost completely self-taught— in other words, they’re experienced amateurs, and that’s just the impression you get when you hear Gershon, Petty, de Matteo, and Cole playing these songs. Even the markedly uneven quality of the material is an asset in that regard; “Every Six Minutes,” with its outraged lyrics, passionately snarled vocals, and sinister, lurking bassline, shows you what the fans see in this band, while uninspired numbers like “My Favorite Sin” and “Ms. Tweak” tell you why there aren’t more of them. And while I doubt that this was actually planned, a cameo appearance early on by Texas Terri and the Stiff Ones supplies a useful bit of context by demonstrating what Clam Dandy is shooting for but missing by just the slightest bit. Unfortunately, all that mostly successful striving after musical verisimilitude is then partially undone by the recording engineer, who seems not to have been quite onboard regarding how the Clam Dandy songs needed to be handled in the studio. Remember, this is, according to the screenplay, a band that has never done a professional recording session. Every song of theirs that we hear is supposed to be either a stage performance or a rehearsal. Actually recording in such situations is much too iffy a prospect to be trusted for a movie, however, so Prey for Rock & Roll understandably resorts to deliberate primitivism in the studio to fake the requisite sound— it’s just that the trickery is only partly successful, in a way that suggests the man behind the desk backing down from what really had to be done. There’s sufficient room sound and little enough separation between the instruments to indicate that the band itself was recorded in a succession of live takes (so far, so good), but Gershon’s vocals are so clear, clean, and upfront— that is to say, so obviously studio overdubs— that it rather spoils the effect. Under the circumstances presented, she ought to be way farther back in the mix, and her sibilant and plosive consonants should sound thicker and less distinct. (In the studio, they generally put special attachments on the vocal mike in order to tighten up those “p,” “b,” and “s” sounds, but nobody ever uses the fragile and unwieldy gizmos onstage or at band practice.) Of course, people who don’t play in rock bands might not notice that at all, but I find it jarring and disruptive to what is otherwise a very well-maintained illusion.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact