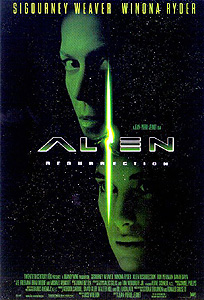

Alien Resurrection (1997) -**

Alien Resurrection (1997) -**

Some of you may recall that when I reviewed Alien3 a bit more than a year ago, I said it would have been serviceable enough as a rip-off of Alien, although it was decidedly wanting as a legitimate sequel. I even said that I’d have been fairly impressed with it if it were a Luigi Cozzi Alien clone. Alien Resurrection, on the other hand, doesn’t measure up even by that very forgiving yardstick. This fourth entry in the series plays like a bad rip-off of the franchise that it came very close to killing off (although sadly not close enough), and I would remain unimpressed with it even if it were the work of Claudio Fragasso and Bruno Mattei. Its nearly top-to-bottom wretchedness is all the more remarkable because the film’s most egregious failures lie with the script, and Alien Resurrection’s writer is one whom I regard very highly indeed. In a twisted way, it’s almost reassuring to see that Joss Whedon is capable of blowing this much sack.

When we last saw Ellen Ripley (Sigourney Weaver for the fourth and final time), she was diving into a vat of molten lead in the hope of preventing the birth of the larval alien queen with which she had been impregnated while in hypersleep aboard the Colonial Marine Corps troopship Sulaco. Now that’s about as stone cold dead as it’s possible for a person to be, yet 200 years later, we find Ripley floating peacefully in a plexiglass tank aboard a different vessel, the United Systems Military starship Auriga. Evidently our Ellen is somehow descended from Grigori Rasputin. Actually, Ripley had a little help cheating death, and strictly speaking, the woman in the tank isn’t really her at all. Rather, she’s Number 8, a clone of the original Ellen Ripley, created from blood samples collected on Fiora 16 (which was called Fioria 161— or, more often, Fury 161— in the last movie; ah, the sweet taste of continuity…). So why the hell would anybody want to do such a thing, beyond the fact that no one much cares to see an Alien movie without Sigourney Weaver? Actually, the scientific staff aboard the Auriga, led by the transparently villainous Dr. Wren (J. E. Freeman, from Copycat and Tremors 4: The Legend Begins), don’t give a shit about Ripley at all, in and of herself. What they want is that alien queen she was incubating.

No, you’re quite right— that doesn’t make any sense whatsoever. Jean-Baptiste Lamarck’s long-discredited theories notwithstanding, acquired characteristics (like baby monsters in one’s esophagus) are not inheritable precisely because they don’t normally alter an organism’s genes. Clone me, and El Santo2 will have a completely functional left knee, with all its articular cartilage intact, and there will be no notch in his incisor to remind him of the time Jenny Hurricane accidentally clobbered me in the mouth with a microphone. Sure, we know from the last film that worker aliens borrow genes from the hosts that carry them as larvae, but there’s never been any indication of a two-way exchange of genetic material between parasite and host— and that’s the sort of thing that Ash would definitely have noticed while he was examining Kane in the Nostromo’s medlab three movies ago! Furthermore, the best biological explanation for the workers’ gene-stealing (that the workers are born haploid males, like drone honeybees, but that they create a second set of chromosomes from their host’s DNA during gestation) wouldn’t apply to queens in the first place. There is quite simply no sensible way that I can see for an alien to be clonable from a sample of Ripley’s blood, let alone to be clonable in situ within a clone of Ripley herself. Whedon has something even sillier than that up his sleeve, too. As an “unexpected benefit of the genetic process” (to quote Wren’s colleague, Dr. Gediman [Brad Dourif, from Graveyard Shift and The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers]), Number 8 not only possesses all of the original Ellen Ripley’s memories, but has also been endowed with the enormous strength, phenomenal agility, hyper-acute senses, and rapid healing of the creature growing inside her. That’s right— she’s Ripley the Vampire Slayer! (And nevermind that none of the previous movies ever portrayed the aliens as possessing any of those particular abilities, beyond the muscle power that would normally be commensurate with their huge size.) Oh— and Number 8’s blood is acidic, too, albeit nowhere near as destructively so as the aliens’.

The plan’s patent ridiculousness aside, Wren, Gediman, and company have cloned Ripley and her internal hitchhiker at the behest of General Perez (Dan Hedaya, of Endangered Species and The Hunger), who has been seduced like three movies’ worth of Weyland-Yutani employees before him by the potential of the aliens as living weapons. This also doesn’t make any sense, because Weyland-Yutani no longer exists (which would tend to imply that its in-house records don’t exist anymore, either), and so far as anyone has ever been able to determine, the queen Ripley was carrying 200 years ago was the last representative of its species anywhere in the galaxy. Given both that the company’s dealings with the aliens were always a closely guarded secret— even within the company itself— and that virtually everybody on Earth either never knew or refused to believe that the creatures existed even back then, how in the hell did Perez find out about the species, let alone get this big an operation off the ground in pursuit of its resurrection two whole centuries later? The logistical half of that question becomes even more pressing when we discover that Perez is pulling a Burke on us, acting illegally and solely on his own initiative. That’s why the Auriga is cruising untold light-years outside of United Systems space, and it’s also why Perez has contracted with a crew of space pirates for the next phase of the undertaking. Once the baby queen has been surgically extracted from Number 8’s body, she’s going to need hosts for her offspring, and thus is the Auriga on its way to rendezvous with a privateer freighter called the Betty, under the command of one Frank Elgyn (Michael Wincott, from The Crow and Along Came a Spider). (Incidentally, score one more for my haplodiploidy theory. The workers obviously aren’t parthenogenetic clones of the queen herself, so if she can start breeding as soon as she’s mature, without ever coming into contact with a male, that must mean the workers hatch from unfertilized eggs. That would almost certainly make them haploid, and if the aliens have only two castes— as seems to be the case— then they would pretty much have to be male, too.) Elgyn and his crew don’t know to what purpose, but they’ve been hired to deliver twelve hypersleep chambers to the Auriga, each of them with a live passenger inside.

Actually, there’s one person aboard the Betty who does know what Perez and Wren are up to, at least in outline. Her name is Call (Winona Ryder, from Bram Stoker’s Dracula and Beetlejuice, who I’d forgotten was about the second cutest thing on Earth in 1997), and she only just joined Elgyn’s crew. Through means that Whedon will be keeping under his hat until after the point where I break off this synopsis, Call discovered Perez’s breeding project, and she signed on aboard the Betty in the hope of infiltrating the Auriga, and killing Number 8 before Wren and his people have a chance to extract the larval queen. Elgyn has no idea that Call is pursuing her own agenda, but he fully expects Perez to try to fuck him somehow, so he arranges for three of the regular Betty astronauts— Johner (Ron Perlman, of Hellboy and Outlander), Christie (Gary Dourdan), and Vriess (Dominique Pinon, from The City of Lost Children and Hellbreeder)— to be packing all sorts of heat when they go aboard the Auriga; Call, Sabra (Kim Flowers), and Elgyn himself go unarmed like they’re supposed to. Now it might seem that a simple drop-off mission like this one would afford Call little opportunity to meddle in the general’s affairs. However, Elgyn has fortuitously finagled Perez into permitting the Betty crew to spend a few days on the Auriga in order to… well, in all honesty, there doesn’t appear to be a reason. Damnit, Joss! I’m getting really tired of things not making any fucking sense in this movie! I suppose I can understand if you slept through ninth-grade biology and lack even the most rudimentary understanding of how genes work as a consequence, but when a writer of your caliber can’t concoct a defensible excuse for the characters to remain in the setting, it’s definitely time to put the story out of its misery and try something else. And you know what? Even having the screenwriter cheat on her behalf doesn’t do Call any good, because the scientists have already removed the queen from Number 8’s body by the time Call manages to sneak into the clone’s holding cell for an assassination attempt. In fact, the queen has already begun laying eggs, Wren has already exposed the pirates’ human cargo to the creatures growing inside those eggs, and indeed there are already eleven adult workers locked up in a monster-drool-resistant plexiglass cage in Wren’s laboratory. (We’ll learn later on that the larva inside the twelfth host— Purvis [Leland Orser, from Seven and The Bone Collector], to give the unfortunate man his proper name— is taking its sweet time in incubating, and that Purvis is being allowed to wander the relevant section of the lab, shut in but otherwise unmolested, in the meantime. There doesn’t seem to be any reason for that, either.) The caged aliens figure out a way to escape (and a very clever one, at that) just as Call is being arrested after her fruitless visit to Number 8’s cell, and all hell breaks loose throughout the Auriga. Good thing Ripley the Vampire Slayer is around to take the situation in hand, huh? Perhaps, but Joss Whedon still has the Ace of Things That Make No Damn Sense At All as his hole card, and you’re not going to believe the Krakatau-scale bullshit eruption that occurs when he finally gets around to playing it.

All the while I was watching Alien Resurrection, I wanted very badly to believe either that Whedon had been called in to clean up an Alien3-style screenplay disaster area, or that studio meddling had rendered what he wrote unrecognizable by the time shooting was underway. After all, Whedon spent most of his movie career (as distinct from his television career) as a script doctor, and the dismal precedent of Buffy the Vampire Slayer was only five years in the past when Alien Resurrection launched, so either circumstance would seem plausible enough. However, by Whedon’s own admission, what happened here was nothing so simple, and I can see no way to avoid cutting him in for a substantial share of the blame for the titanic idiocy of what should by all rights have been the final Alien film. Alien Resurrection was his story all along, and although the ending went through five studio-mandated rewrites as the remaining fraction of the budget dwindled, director Jean-Pierre Jeunet filmed the script essentially as written in its final draft, except that he played straight a fair amount of material that Whedon had intended as comedy. And frankly, Jeunet was right to downplay the jokes, no matter what Whedon may say to the contrary. What Whedon wrote was a double-length episode of “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” set in outer space, with Number 8 as Buffy, Call as a pre-witchcraft Willow, Vriess as Xander, Christie as a non-love-interest Riley, and General Perez as Principal Snyder. I can’t for the life of me imagine what convinced him that this was an appropriate direction in which to take the Alien series, even before factoring in a third act full of Zardoz-style pseudo-deep mind-fuckery. Ripley should not quip flippantly about the nightmare that has by this point consumed practically her whole non-hibernating life, whether or not she can be technically considered herself anymore. That simply isn’t her style of strength. Androids (oh, come on— like it counts as a spoiler that one of the characters is really a robot yet again) should not suffer from vampire-with-a-soul existential angst over being only outwardly human. That’s a Blade Runner thing, not an Alien thing. The human villains should not be led by a slimy but ineffectual buffoon— still less a slimy but ineffectual buffoon who puts one in mind of a middle-aged Eugene Levy! Whedon has complained in interviews that Alien Resurrection was cast wrong, played wrong, designed wrong, and scored wrong, and for the most part, he’s right about all of that. However, none of the things that Jeunet, the cast, or the producers bungled at their ends went nearly as far toward making Alien Resurrection a crummy movie as Whedon’s contribution in writing it wrong to begin with, and none of those other people’s mistakes would look nearly as dire were it not for their interplay with the inexhaustible fountain of bad ideas that is the film’s script.

Let’s begin with the production design. The aliens this time are sad shadows of their former selves, three generations of subtle makeovers having finally buried all but the contours of H. R. Giger’s beautifully and elegantly horrid original design under successive layers of putative “improvements.” Here in their fourth incarnation, the creatures are pointier, slimier, glossier, and wrinklier than ever before, but they’ve also ceased to resemble products of an alien nature, and are now just regular old movie monsters. The physical changes wouldn’t be so grating, though, if Whedon had at any point portrayed the aliens as a credible threat. For all the pants-shitting engendered by their escape from the lab, they really don’t do much of anything. General Perez’s soldiers immediately pile aboard the escape pods to evacuate (thus sparing us all Jeunet’s James Cameron impersonation), but Number 8 and the poorly armed space pirates do just fine without them— and believe me, nothing does more to diminish the stature of an otherworldly menace like seeing it get a face full of clock-cleaner from a dwarf in a motorized wheelchair. Then there’s the new creature Whedon added to the Alien bestiary, the centerpiece of that Krakatau-scale bullshit eruption I mentioned earlier. Although Whedon swears that it was not his intention for the human-alien hybrid to be “a withered, granny-lookin’ Pumpkinhead-kinda-thing,” the mere fact that it was conceived as a human-alien hybrid in the first place virtually guaranteed that it was going to suck. None of the earlier design concepts I’ve seen were any better than what made it into the completed film. As for the inanimate elements of Alien Resurrection’s production design, the big problem there is that we’re presented no visible evidence of the vast amount of time that’s supposed to have passed since the last movie. Except for even greater extremes of pointless starship gigantism (the Auriga has a crew of just 48, yet it must be about 30 kilometers long), the technology on display here looks exactly the same as what people were using two centuries before. Again, though, that just serves to underscore a defect in the script, for nothing has changed socially or politically in a way that affects the story, either, and you really have to ask what purpose was supposed to have been served by the 200-year inter-episode interval.

On the casting front, the most conspicuous mistake was bringing in Winona Ryder to play Call. Ryder is not a terribly versatile actress. She was great at playing strange and troubled modern-day teenagers in her youth, and I bet she could pull off a strange and troubled modern-day woman in the grip of suspended adolescence even now. Cast her as an idealistic but self-loathing 27th-century (or thereabouts) space pirate, on the other hand, and you get a performance almost as worthless as her infamous turn as a prim but feisty Victorian lady in Francis Ford Copolla’s majestically misconceived Dracula film. Still, Call is a character who becomes harder to swallow with each new detail we learn about her anyway, and more appropriate casting might not have helped very much. The same goes for the pirate crew as a whole, albeit to a lesser extent. These characters just plain didn’t belong in the Alien universe even before Jeunet decided to treat them like the vegetarian terrorists in his earlier Delicatessen, so it really doesn’t matter how ridiculously overbroad Ron Perlman, Dominique Pinon, and Gary Dourdan are.

In the end, there are just two decent things about Alien Resurrection, one of them very specific and the other very general. The former is the scene in which Number 8 discovers the laboratory where the results of the preceding seven attempts to clone Ripley are kept, which reminds us all too briefly of what a dark and threatening place the Alien universe was meant to be. It lasts five minutes, if that, but for that short span of time, we get a faint echo of the power this series once wielded. The more general highlight is, expectedly, Sigourney Weaver’s performance. As in Alien3 (but significantly more so), Weaver delivers a fine execution of a terrible idea. She makes Number 8 look far more dangerous than this installment’s lamentable crop of monsters, and she sells the clone’s ambiguous species loyalties as completely as could be asked for such a daft notion. Her mimicry of the aliens’ body language is also perfectly unnerving on those rare occasions when the gestures in question are among the creatures’ repertoire from the first two movies, back when they were actually scary. So effective is Weaver’s Number 8, in fact, that I keep finding myself trying to invent premises to which she would be more properly suited. I think my favorite idea in that direction thus far is to make Number 8 the Vol counterpart in a sequel to Species patterned after The Brain from Planet Arous. Tell the truth, now— wouldn’t you much rather have seen Sigourney Weaver taking down a monsterized Natasha Henstridge in a no-holds-barred, super-powered catfight than anything that happens in Alien Resurrection?

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact