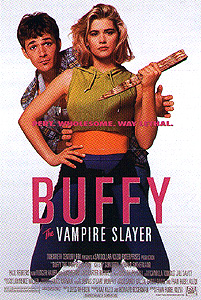

Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1992) *½

Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1992) *½

I’m not a great watcher of series television— haven’t been since I was a kid. It’s been years since I actively followed even a single show, and frankly I’m happy with that state of affairs. I really don’t like having an ongoing weekly obligation to my television set, and what TV I do see on those occasions when I tune in to investigate whatever show has the people I know all hot and bothered almost invariably demonstrates that I’m not missing much. I gladly made an exception, however, for “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” and its spin-off series, “Angel.” For more than five years, I went out of my way not to miss an episode of either show, and I’d have kept that vigil through the end of the final “Angel” season, too, if the fucking University of Maryland basketball team hadn’t performed well enough that year to get about three out of every five episodes bumped from their usual timeslot in the DC television market. “Buffy” and “Angel” are also the only non-anime series that I own on DVD, and indeed apart from the 1960’s incarnation of “The Outer Limits,” they’re about the only live-action TV shows currently on the DVD market that I have any particular desire to own. (Well, okay. I bet I’d buy the original “Star Trek” series, too, if it weren’t so unconscionably expensive.) I even have a bootleg copy of the unaired half-hour pilot that series creator Joss Whedon used to convince the network that a weekly television program based on a five-year-old movie that had turned about 75 cents’ worth of profit in the theaters was a good idea. In short, I am a big fucking “Buffy” geek, and I’m not at all ashamed to admit it. I was not, however, part of that first crop of fans that embraced the show in its initial run as a mid-season replacement in 1997. In fact, I didn’t start watching until about three quarters of the way through the second season. Why not? Because I’d seen a good-sized chunk of Buffy the Vampire Slayer, the movie, and I knew well the qualitative plunge that generally occurs when a feature film is turned into a TV series. If the movie was this lousy to begin with, what the hell hope did the premise have on the small screen?

The first thing we need to establish is that in Whedon’s parlance, a Vampire Slayer isn’t just somebody who goes around killing vampires. Rather, she is one specific, super-powered girl who is reincarnated throughout the ages in order to protect humanity against the vile scourge of vampirism. The Vampire Slayer (and there can be but one in each generation) is faster, stronger, and more agile than any normal human, and she can tell when there are vampires about because her body reacts to the proximity of their unnatural energy by having uterine cramps. The Slayer is not completely alone in her battle, however, for whatever mystical force causes her perpetual reincarnation also causes the similar recurrence of the Watcher, the wise man who trains and prepares her for the fight, teaching her how to exploit her superhuman abilities. Unlike the Slayer, the Watcher— Merrick (Donald Sutherland, from Die, Die, My Darling! and Citizen X)— retains his memories and identity from one lifetime to the next; those millennia of accumulated lore are a good thing to have, seeing as Merrick is supposed to be the brains of this outfit. Unfortunately, Merrick never knows, when one Slayer dies, who the next one is going to be or where he’s supposed to find her. When such a transition takes place, he must scour the globe for a girl with the Mark of the Covenant, a certain mole-like growth just beneath her left clavicle. (Those familiar with the TV show will notice some major differences between this version of the Vampire Slayer back-story and the later one.)

Let’s leave all that aside for the moment, though, and head over to Southern California to meet five of the worst human beings on the face of the Earth. I’m talking about Hemery High School senior and head cheerleader Buffy (Kristy Swanson, of Flowers in the Attic and Deadly Friend) and her squad of malignant Valley Girl sycophants, Kimberly (Hilary Swank, from Sometimes They Come Back… Again and The Core), Cassandra (Natasha Gregson Wagner, from Urban Legend and Mind Ripper), Jennifer (Troll 2’s Michele Abrams), and Nicole (Paris Vaughan). We spend the first several scenes almost constantly in their company, and let me tell you, if Whedon and director Fran Rubel Kuzui had wanted to get us rooting at once for the bad guys, they could have done no better than to make us spend a significant amount of time with this bunch. They bitch. They whine. They natter. They heap scorn and belittlement upon anyone and everyone who is not as rich and spoiled and beautiful as they are. They obsess over their tacky clothes and their petty grievances and their tawdry positions of inconsequential status and unearned privilege, and Jesus Fucking Christ, can we please get somebody with fangs and a cape over here to eat these noxious cunts already?!?! Sadly, no, for not only are all too many of them destined to survive to the closing credits, but the leader of the pack is the latest incarnation of that Vampire Slayer chick I was talking about a moment ago. Merrick has been having a hard time finding her, you see, because being an LA girl, she of course considered the Mark of the Covenant an intolerable blemish, and had it removed at the earliest opportunity. He’s finally looking in the right city, at least, and he’s getting warm enough to be seen haunting Buffy’s hangouts from time to time, but actual contact has as yet eluded him.

Meanwhile, the vampires have come to Los Angeles, too. These aren’t just any vampires, either, but some big-shit vampire king guy named Lothos (Rutger Hauer, from Blade Runner and the second TV version of ‘Salem’s Lot) and his seriously tweaked henchman, Amilyn (Paul Reubens, aka Pee Wee Herman, looking remarkably like his mugshot from that time the cops caught him beating the bishop in a porno theater). Now you’d think a vampire as important as Lothos is supposed to be would have an army of the undead at his disposal, but evidently the recession of the early 90’s has meant layoffs in the blood-based sector of the economy, too, because Amilyn is it— at least until his recruiting drive among the students of Hemery High has a chance to gain some traction. Among the early conscripts are Grueller (Sasha Jenson, of Ghoulies II and Halloween 4: The Return of Michael Myers), a jock buddy of Buffy’s boyfriend, Jeffrey (Randall Batinkoff, from The Stepford Children and Blue Demon); Benny (David Arquette, from Ravenous and Scream), the best friend of official school weirdo Pike (Luke Perry, of Invasion and Descent); and even Buffy’s sidekick, Cassandra. But for some reason that must have been left on the cutting room floor, the Hemery student Lothos wants most is Buffy herself, whose dreams he visits in a most stalkerish manner, and whom he may or may not recognize at this point as the current incarnation of his arch-nemesis.

Merrick finally catches up to Buffy after school one day, while she’s working on her gymnastics. (By the way, Kristy Swanson’s sturdier build and markedly superior state of physical fitness make her a more outwardly credible Vampire Slayer, even if Sarah Michelle Gellar out-performs her in every other respect.) She understandably takes him for something between a uniquely imaginative dirty old man and an exceptionally articulate deinstitutionalized mental patient when he begins delivering his spiel about destiny and reincarnation and mystic birthrights, but the fact remains that he knows plenty of things about Buffy that she simply can’t account for. He knows about “that big, hairy mole;” he knows about her recurring dreams of battling Lothos in different identities throughout the ages; hell, he even knows who, when, and where she was in each of those dreams. And when he finally succeeds in convincing Buffy to humor him with a trip to the cemetery that night, no denial or “rational” interpretation that she can devise will explain away the two vampires that rise from their graves (this apparently happens like clockwork on the third night following a fatal attack) and attempt to kill her and the Watcher. Luckily, she really does have those supernatural powers Merrick told her about, so she has surprisingly little trouble (well, it surprises her, anyway) defeating these first undead foes of her career. Pike, too, encounters vampires in ways too obvious to be ignored or denied, and when he and Buffy cross paths while she’s out hunting and he’s being chased by Amilyn and his newly hired minions, they decide to combine their monster-fighting efforts. There’s one problem Merrick has not foreseen, however. He constantly stresses the importance of Buffy keeping her Slayerhood a closely guarded secret, so as to forestall the day when Lothos comes for her. But if Amilyn is out making vampires out of her schoolmates, it will inevitably be only a matter of time before she winds up in a fight against somebody who knows her from her regular life, and the charade will be over at once should any such bloodsucker escape to pass on what he knows.

Joss Whedon has never exactly been shy about his displeasure with the way Buffy the Vampire Slayer turned out, but I think the surest measure of it is how much of his script for the movie got recycled into the first season of the TV series, even as the details of the premise, mythos, and cast of characters were revised wholesale. It’s not just that both characters have the same relationship to Buffy— apart from his slovenly appearance and the discarded reincarnation bit, Merrick is Rupert Giles. Lothos may bear little outward resemblance to the Master, but the latter would replay several of the former’s scenes with remarkable fidelity. (And when the Master obsessed over the Slayer, something eventually came of it.) The Pike-Benny relationship is echoed by Xander and Jesse in the TV show’s premiere episode, and Pike in general resembles a slightly awkward composite of Xander and Angel (with maybe just a hint of Oz thrown in, too). Even seemingly inconsequential things carry over. Hemery High’s mascot is the hog, while Sunnydale High’s is the razorback; the movie’s inept, new-agey school officials are effectively reincarnated in the TV version’s Principal Flutie; Pike lives above a bar that looks an awful lot like the Bronze. The most surprising bit of recycling concerns Buffy herself, however. If you’re a fan of the television series, back up a few paragraphs, and reread the part about our introduction to the title character. Doesn’t sound like Sarah Michelle Gellar’s Buffy at all, does it? It does sound familiar, though, yes? That’s right, the movie’s Buffy is the TV show’s Cordelia Chase, right down to the worshipful but untrustworthy pack of dim-witted toadies! It makes sense when you think about it. Gellar’s characterization is hardly what springs to mind when you hear the phrase, “Buffy the Vampire Slayer.” One expects a girl named Buffy to be stupid, frivolous, superficial, and insufferably catty, which is exactly what Kristy Swanson’s interpretation starts out being. Appropriate or not, however, it makes her incredibly unsympathetic, to the extent that most viewers are likely to agree with the sentiment when Benny (a vampire by that point in the story) incredulously asks Pike, “Why do you like these people?!” while the latter boy assists Buffy in defending the senior class against a mass vampire attack.

Now, you’ll notice I just said that Movie Buffy starts out being stupid, frivolous, superficial, and insufferably catty. The developmental arc for her character in the movie is away from that Cordelia-like persona, and toward something more closely resembling the Buffy we know from television. The greatest failing of Buffy the Vampire Slayer is that no one involved— not Joss Whedon, not Fran Kuzui, and certainly not Kristy Swanson— ever manages to sell it. When the TV show eventually worked a similar transformation on Cordelia, Whedon and company had four years (counting the first season of “Angel”) in which to do it, but the movie has less than 90 minutes to spend turning Buffy into a human being. None of the things Buffy goes through after her first talk with Merrick seem sufficient to produce the necessary changes in such a short span of time, nor do we ever get the sense that Buffy’s vampire-related hardships are bringing out hidden qualities that were really there all along. With all the space for real character development being gobbled up by mythos exposition instead, and with what few attempts the running time permits being scuppered by Swanson’s sharp limitations as an actress, the movie is forced to rely on a rather clumsy sartorial shorthand— as Buffy rises to the challenge of her destiny, she increasingly dresses less like a Valley Girl princess and more like a scruffy grunge chick. Some of her revised fashion sense can be dismissed as simple practicality (who wants to ruin her $200 designer jeans by wrestling with a vampire on a fresh grave?), but the sneakers and sweatpants we already know she has in her closet somewhere would have been just as workable an alternative. No, if she’s suddenly dressing up in gray flannel and chunky boots (neither of which one would expect to have found anywhere in her previous wardrobe), there’s a conscious decision in back of it, specifically a decision on the filmmakers’ parts to associate their heroine with a youth subculture that was popularly identified with both female empowerment and rebellion against materialism. The shortcut might have been minimally successful in 1992, but as grunge (together with externally similar but more politically attuned contemporary countercultures, like the riot grrrl movement and emo in its original, post-hardcore sense) recedes deeper into the pop-culture memory hole, the weaknesses of characterization that it was adopted to conceal become ever more plainly apparent.

The unpersuasiveness of Buffy’s character arc may be the movie’s most serious defect, but it is far from the only one. In fact, Buffy the Vampire Slayer draws attention to the things that later made the TV show so good by being unable to equal any of them. The series vampire makeup was like a more developed version of that used in Fright Night, and had to be toned down after the first few episodes out of concern on the part of the producers that it was too horrifying for television; the vampires in the movie have obviously plastic fangs and Spock ears that look like they came from Archie McFee. The TV show had fight choreography competitive with that of any Western action film, overseen by stunt coordinators with considerable martial-arts training; the movie has huge crowds of vampires standing around patiently awaiting their turns to be punched in the face. On television, we routinely got career-high performances out of actors who rarely managed to be more than passable in anything else; the movie gives us Donald Sutherland and Rutger Hauer behaving as if Kuzui spent the whole of the shoot badgering them for less subtlety and clunkier line readings. But most importantly, “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” consistently offered both some of the smartest humor on television at the turn of the 21st century and the most committed horror to be produced for network broadcast since the early 1970’s. Buffy the Vampire Slayer, on the other hand, feels like it was made for TV in both departments. Let’s face it— there aren’t too many worse condemnations for a modern horror comedy than that.

This review is part of a much-belated B-Masters Cabal tribute to all the living dead things that we’ve been negelecting in favor of zombies all these years. Click the link below to read all that the Cabal finally came up with to say on the subject.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact